Corporate lawyer John Willding, a partner in the Dallas office of Barnes & Thornburg, has developed a successful midmarket transactional practice with a particular niche representing entrepreneurs – he’s helped some sell their businesses at exponential multiples of the startup costs.

He also is quite the social entrepreneur.

Last month, Willding celebrated the 20th anniversary of his regular networking happy hour that started with only a couple of people. Over the years more and more of them heeded his exhortation-cum-mantra to “bring a friend next time.” The crowds grew to as many as 800 to 900 in pre-Covid days for his Last Tuesday (of-the-month) events at the Dallas Ritz-Carlton hotel’s Rattlesnake Bar.

Covid realities and restrictions crashed the parties in April 2020 and caused a nearly yearlong hiatus. But when vaccinations began to ease fears, he re-opened this spring, and numbers again reached into the hundreds.

“I respected all the rules of Covid for a year,” Willding says, acknowledging the short-lived respite that has been dashed somewhat by Covid’s Delta variant. “We’ll see how it goes now.”

Willding, 48, is a transactional lawyer by both training and nature, but his networking parties are decidedly non-transactional, meaning not the typical law firm way of inviting potential clients with an expectation of being hired. He wants just about everyone there.

Indeed, Willding seems to have an aversion to typical ways of doing things, and it began early in life. Two nuggets now, more later: He enlisted in the Army as a teen and got Ivy League credentials in night school.

For the monthly mixers, he had three rules from the get go: No speeches, no sponsors, no name tags. Willding drops $500 out-of-pocket for wine, which might barely be enough to prime the pump, and the hotel’s cash bar takes it from there.

“The art and science of this is that I put quality people in a big room and let them do their own thing,” says Willding. “If they do business together, awesome. If they hire someone or get a date, that’s awesome. It’s not a place to get hired or to find a CFO or a date, but all those things happen.”

Willding with Sara Jones (l) and Yael Gilleland (r)

Indeed, some have told Willding that they met at Last Tuesday and went on to marry.

Willding is a showman. An entertainer. His often two-a-day selfies on Facebook – distribution is limited to his FB friends – are flashy, funny, occasionally political and frequently risqué. Social media can be good for maintaining connections with people even if you don’t see them again for a long time – and he says he wants to reveal his personality there in part to “stay front of mind” with them.

Willding’s personality could fill boxcars with an admixture of exuberance, confidence and stylishness. Those three words happen to compose the definition of “flamboyant.” People who know him say it fits, but in a genuine, joy-riding kind of way.

“He’s equally a large personality in person and in social media,” says Chad Ruback, an appellate lawyer in Dallas, who was introduced by a friend to Last Tuesday years ago and subsequently has brought others along. “And it’s the same personality. Some people you see online are more reserved than in person or vice versa. John is the same in both. It’s a large personality, and a lovable personality.”

As for social media, Willding ended public access to his Instagram account last year. And after some pushback on LinkedIn he toned down his postings there in 2019, going with a dry “professional only” approach. He stopped sending Facebook friend requests about five years ago, accepting ones from others when he chooses. On his nonpublic Facebook and Instagram accounts, he lets it fly.

Willding occasionally posts disclaimers of a sort, such as this one on Facebook copied and forwarded by one of his FB friends. Willding shared a Facebook meme with a photo of the late comedian Richard Pryor, with this large-letter message superimposed: BEFORE YOU COMPLAIN ABOUT ANYTHING ON MY PAGE, ASK YOURSELF, DID I ASK YOU TO FOLLOW ME —————?” That last bit that we expurgated was a Pryor trademark: the compound noun of Oedipal disparagement.

The f-word was punctuation for Pryor. For Willding, who could vie for king-of-selfies on Facebook, it is used mostly for exuberance, with photos of driving his 41-foot cabin cruiser, with maybe an attractive woman or two along for the ride, to him just opening his eyes to greet another glorious day.

“You’re crushing it with the selflies, you’re black-belt level now,” Jason Wright, host of the Texas Titans podcast, told Willding when interviewing him in 2019. “I have on my phone my favorite John Willding selfie, taken in bed when you just woke up. I said ‘Who does that? John Willding does that.’ It shows you’re not taking yourself too seriously.”

Willding next to Ed Opka (center) with Michael Rodriguez (top rear) and friend.

Curtailing his online presence stemmed, in part, from Willding’s experience in moving his networking touch to Washington, D.C. during the Trump administration.

“I’m openly Republican and openly for Trump,” he says. “I’ll tell people I’m a veteran and I voted for Bill Clinton and for Obama, the first time. Things just got out of control the past couple of years, and I tried to do what I’ve always done – be authentic and talk to people about these (political) topics if they’re willing to listen.”

The District, always a rough-and-tumble place, had grown much nastier with the polarization over Trump’s presidency and the rise of cancel culture on all sides. This has been fed by the internet offering neither a presumption of innocence nor a fair trial. Twitter acts as judge and jury. And so on.

Willding at times found himself bathed in unwanted beams of the national spotlight.

He launched First Tuesdays in Washington in March 2018 at the Trump Hotel’s Benjamin Bar and Lounge in the building’s capacious lobby. He would spend that week each month at Barnes & Thornburg’s D.C. office, little more than a paper-airplane flight from the Old Executive Office Building by the White House.

Willding’s profile became more than just “front of mind” when a number of his Instagram photos and postings became fodder for a reporter running a blog-newsletter, “1100 Pennsylvania,” on the comings and goings of Republican Who’s Who types and related hangers-on at the Trump Hotel during Donald Trump’s presidency, with an emphasis on politics and money.

Willding’s First Tuesday gatherings there were chronicled in the online publication, and that led to his inclusion in a New York Times feature in October 2020 headlined “The Swamp That Trump Built: A businessman-president transplanted favor seeking in Washington to his family’s hotels and resorts — and earned millions as a gatekeeper to his own administration.”

The feature noted that the hotel attracted Trump staffers, cabinet secretaries, donors, Trump children and many “Fox personalities.” Then there was this paragraph:

“Washington’s influence class flocked to join them. In early 2018, according to Facebook posts, John Willding, a lawyer at Barnes & Thornburg with business before the government, began hosting a monthly mixer that came to be known as Trump First Tuesdays. Hotel staff would reserve a corner of the room with a velvet rope. Mr. Rivera, the former bartender, recalled that some guests would run up bills as high as $30,000 on those and other nights.”

To those who know Willding, he was not trying to make money or raise it. He was there being “John Willding,” the maestro at facilitating new or renewed professional relationships, while basking among kindred spirits.

Willding suddenly was a player on the D.C. stage. At the BLT Prime restaurant in the Trump Hotel, he and a group visiting from Texas dined one evening at Table No. 72. It is Trump’s own table and mostly reserved solely for him and his company at any time. This special dinner was, of course, documented with a photo Willding put on Instagram, which soon found its way onto the screens of “1100 Pennsylvania.”

“I hate the victim culture, but I got attacked for being openly Republican,” Willding says. “Things just kind of got out of hand the past couple of years, and I was just trying to do what I’ve always done, be authentic. I’ll never run for political office. If you hold public office you get a lot of scrutiny; but there’s a problem when you apply that same level of torture to just ordinary human beings. That’s caused a lot of good people to pull back.”

Covid ended the D.C. First Tuesdays in March 2020.

“I refused not to participate, though that is what a lot of law partners do,” Willding explains. “They don’t take on social topics. I just take the position that you can either have no expression whatsoever or you actually allow people to know your personality and get to know you better, and that’s the approach I take. I’m a passionate guy and sometimes it gets me into trouble, but at the end of the day I’ve done everything I can to promote good in this world.”

Indeed, Willding also brings his passion, personality and networking skills to community service, including his significant role for the past 16 years with the S.M. Wright Foundation, a nonprofit helping underprivileged children and needy families in Dallas’ inner city. The foundation’s signature effort, among its other year-round work, is “Christmas in the Park,” providing toys, food, clothing and household necessities for those in need.

He has been co-chair of “Christmas in the Park” and chair of the Beds for Kids program.

“John has been a huge help with Christmas in the Park and our other efforts,” says H.M. Wright III, the foundation’s president and CEO. “He has a wonderful gift for bringing new people to help and getting them involved in the cause. What I love about John is how he connects with people and that skill and gift resonates, making them want to be involved.”

Apparently it has always been thus. As an associate at Hughes & Luce in the early 2000s, Willding offered to help when a fellow associate brought in a couple of barrels for collecting food donations at Thanksgiving.

“When John got into it, one or two barrels weren’t enough,” says Fred Barrow, now claims director for employment law insurance with Chubb in Dallas. “We had to bring in another two barrels. He was always one octave higher in everything he did.”

Barrow, noting that he is African American and a Democrat, says, “I hope people see John is a giver, not just a big Facebook or Instagram person or big personality. I know who he supports and I know where he is on that, but it’s all the other stuff that makes you say, ‘I still enjoy this guy because of the things he’s getting done, the things he’s doing. He’s making a difference.’”

John Willding’s résumé reads like a traditional roadmap to success: Southern Methodist University, Rutgers Law, Harvard master’s. But he beat a very different and sometimes rocky path all along the way. He bootstrapped.

(From Left) Vinny Thomas, Michael Rodriguez, Willding, Sara Jones

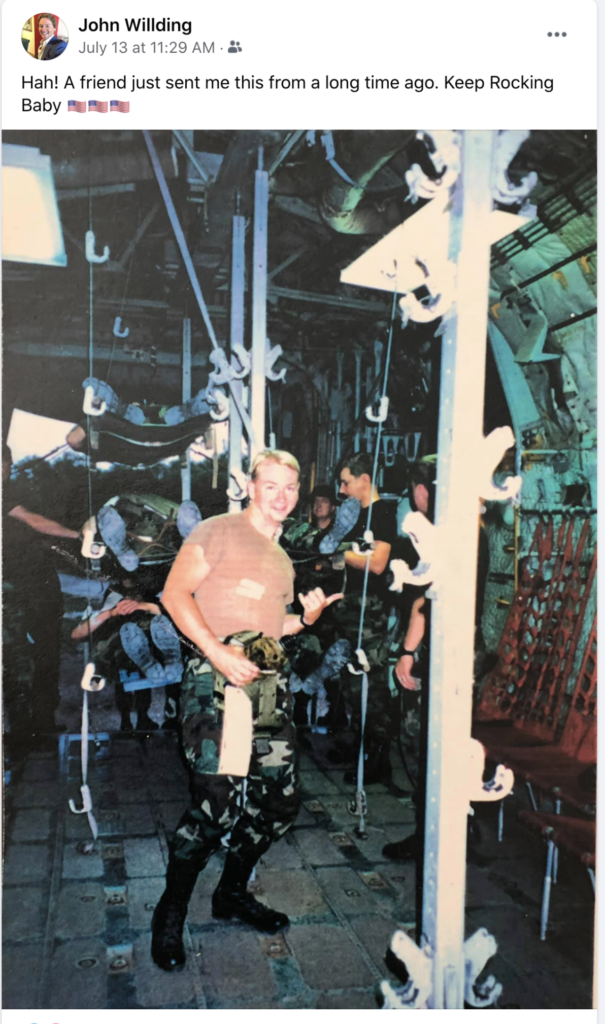

Because his parents were considerably older than most when he was born, Willding knew he would be on his own financially. He joined the Army reserves as a 17-year-old high school student. After graduating, he went on to serve nearly two years as an enlisted man on extended active duty, then eight more years in the reserves.

After active duty, Willding enrolled at the Dallas Community College for two years, while working full time at the Bent Tree Country Club golf course. His better than 3.5 GPA led to acceptance in the Southern Methodist University evening program for a bachelor’s degree, where tuition rates were $200 per credit hour, rather than the $600 day students paid. (Though a number of his classmates were regular students who didn’t want to get up early in the morning.) He worked days full time at the golf course.

“The Army really made me grow up and gave me a perspective on life none of the other kids had in my class,” Willding says. “I’d learned how to start and finish something.”

A mix of good grades, military background and geographic diversity earned him a scholarship at the Rutgers School of Law, from which he graduated in 2001. But Willding craved a broader education, more particularly an Ivy League degree. While in law school full time, twice weekly he took 16-hour round-trip train rides from nearby Philadelphia to Boston, where he took night classes for his Harvard University degree: Master of Liberal Arts in Government.

Amtrak provided a rolling study hall for completing his assignments at both schools. Bonus: The law school accepted 16 credit hours from other graduate programs.

Willding has been on the board of directors and was program chair of the Harvard Club of Dallas. Probably few there worked as hard for the credentials. Harvard is part of his networking allure.

Along with Willding’s unconventional approach to education, there was a lot of juggling. After clerking for a federal judge in Houston in 2001, he hustled back to Harvard for a semester and a summer to finish his coursework. Then, while an associate at Hughes & Luce, he completed his master’s thesis, getting the degree in 2005.

The thesis dealt with Enron and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, a regulatory-tightening in response to the financial scandal. Willding had been in the courtroom as a law clerk to U.S. District Judge William Hoyt, the federal judge who accepted the guilty plea of Enron’s former CFO Andrew Fastow and sentenced him to six years in prison.

Willding’s paper reflected a concern for the impact of regulations through initial overreach and later correction: “I tracked a rare simultaneous and significant increase in IPOs and de-registrations of small public companies that could not afford the new and increased compliance costs,” he explains.

Judge William Hoyt, now on senior status, had hired Willding as a law clerk without even interviewing him. The judge instead spoke at length on the phone with the young man’s mother, who was disabled and home-bound.

“John was a devoted son and I was impressed with that,” Judge Hoyt told The Texas Lawbook in a telephone interview. The judge, the second Black member of the federal bench in Texas, spent six years as an officer in the Army reserves. He was with a tank unit in the armored branch, not J.A.G.

The judge said he appreciates the discipline and maturity that come with the military experience and with facing unusual challenges.

“It tells me a lot about whether they’ll make a good clerk, more so than being a good academician,” said Judge Hoyt, a Ronald Reagan appointee who took the bench in 1988. “I’m not as concerned with them being smart as being wise. John had that.”

And more. While Willding wasn’t born with a silver spoon in his mouth, there is the golden tongue.

Willding likely would have been a top-drawer litigator. He started out briefly in litigation at Hughes & Luce, but the drudge work of document review was a tough sell on someone who had just spent a year working for a judge and spent time almost daily in a federal courtroom. And his networking — this is when he launched Last Tuesday – mixed with a natural tendency to just make things happen, led to something unusual in law firms: The young associate soon was bringing in clients for partners.

“He was doing fine work on the litigation side,” says Barrow, then Willding’s fellow associate. “But because of what he was able to do, due to his own personal magnetism and drive, that lent itself extremely well for corporate work, such as meeting entrepreneurs — people who really have a different bent to them in terms of doing big deals.”

Listening to Willding explain his and his more than 700-lawyer firm’s successful midmarket approach, and his thoughts on a variety of topics, gives the impression that he probably has a clear, sharp and engaging elevator pitch for just about anything.

A couple of samples:

“Barnes & Thornburg has always been the best firm in Indiana since the beginning of time and brings that to our offices around the country. Incidentally, our firm moved up more on the AMLAW 100 than any other firm in America this past year, with organic growth and consolidation of law firms. We opened in New York during Covid and brought in lawyers from big firms there with our financial strength, zero debt and ability to match or beat salaries and with substantially reduced billing rates.”

And, “My passion is representing entrepreneurs. They’re owners. They’re creators. I want to be a trusted adviser. It’s their money and they can have trust in me. I’m able to work with companies that first are startup or small to medium size. Not a lot of legal needs, but as they grow and business becomes more sophisticated and enters different geographic territory, I can help. I’m basically outside general counsel they’ll call for whatever legal need. I often help them or refer them to others. The place I want to be is getting that call. We’re the heavyweight in that middle market space. Other firms can do some other things, but in middle market, we’re a leader.”

“John’s really tuned in to middle market companies, tuned in to privately held founders and usually principal owners,” says James R. Browne, a tax law partner at Barnes & Thornburg who works as what he calls “the architect” for Willding’s “general contractor” work on the deals. “He knows what’s important to the entrepreneur, and he’s very good at just getting to closing. He knows what’s important to fight about and what not to fight about, and how to bring the parties together.”

Willding joined the Army Reserves at 17

Willding was involved in bringing Browne to Barnes & Thornburg in 2016 from what then was Strasburger & Price, a year after Willding made the same move.

It was part of a series of major consolidations among Texas law firms in recent years, particularly with national firms based elsewhere.

Browne gives testimony to Willding’s passion for Last Tuesday gatherings. They were playing golf in Palm Springs, California, where Browne has a vacation home, when a powerful storm hit Dallas.

“He was really nervous,” Browne says. “Flights to Dallas were canceled and he was beside himself because of the Last Tuesday happy hour. He said he had never missed one.”

Willding was constantly on the phone trying to work out a way to get back in time. Eventually he did.

“Then I learned that he missed the happy hour two months later for a significant opportunity,” Browne says with a chuckle.

Willding was on the host committee for a dinner for Bill Clinton in Austin. It was late in the Obama administration, and Clinton was speaking on foreign investment.

“That’s the only time I’ve missed in 20 years, other than the Covid break,” he says.

Willding had expanded Last Thursdays to the Plano-Frisco area in 2019, but they haven’t yet resumed since Covid halted the expansion.

“It sounds strange, but John has never met anyone who didn’t think John was their friend,” says David G. Luther, of counsel at K&L Gates in Dallas, and who was a partner at Hughes & Luce when Willding was an associate. “He is sincerely interested in everyone he meets and seriously interested in you being his friend, and that comes across.”

Luther says of Willding’s strategy of repeatedly encouraging Last Tuesday goers to reach out to bring their own contacts: “It was almost a reverse Kevin Bacon.”

John Willding may well be within 6 degrees of everyone in Texas, if not the whole country.