©2021 The Texas Lawbook

It was pouring rain across North Texas on Oct. 24, 2019, the day Joshua Russ drove from Plano to Sherman to resign from his dream job at the Department of Justice. It was the kind of downpour you remember later, like the night two decades earlier when Russ lost his grandfather, a storied Texas prosecutor.

Russ hadn’t slept much the night before his resignation — not because he agonized over whether to stay or go, but because resigning was the most painful of the choices before him. It was also, he concluded, the only real choice.

Joshua Russ had become a whistleblower.

The same day Russ announced his resignation, he filed a whistleblower complaint with the DOJ’s Office of Inspector General claiming that politically-appointed superiors interfered with his investigation and potential civil and criminal prosecution of retail giant Walmart’s role in the nation’s opioid epidemic.

For more than a year, Russ had been ready to file a landmark federal lawsuit in East Texas that accused Walmart and its 5,000 pharmacies of turning a blind eye to thousands of opioid prescriptions they knew to be suspect, all violations of the Controlled Substances Act. The lawsuit — eventually filed by the Justice Department in Delaware more than a year after Russ resigned — alleges that the company not only knew about the bogus prescriptions but failed to take previously agreed upon actions to curtail them — a failure that prosecutors believe likely contributed to thousands of deaths, not just in East Texas, but nationwide.

Russ’ resignation was felt throughout the DOJ, as he co-chaired the agency’s Prescription Interdiction & Litigation Task Force, a multi-jurisdictional effort to thwart easy access to opioids.

In an exclusive interview with The Texas Lawbook, Russ said he was “handcuffed by political appointees” and “wasn’t able to do the key investigation” into Walmart.

Main Justice interfered, he said, in his team’s efforts to collect “key evidence core to the case.”

“I had never seen that in an investigation,” said Russ, who served as an assistant U.S. Attorney and chief of the Eastern District of Texas’ civil division.

The OIG and the Justice Department declined to comment on Russ’ whistleblower complaint, or declined to answer questions provided by The Texas Lawbook.

Walmart reiterated its long-held position to The Lawbook that the DOJ’s investigation into the company was “riddled with misconduct.”

Although Russ was a well-regarded force driving the opioid enforcement effort, his role in the investigation had become a sticking point in the delicate politics of prosecuting the world’s largest corporation. He became a target of the Walmart defense.

In October 2020, Walmart filed a federal lawsuit against the DOJ in Sherman, Texas, claiming that the Eastern District’s investigation and possible criminal and civil litigation were “riddled by unethical conduct.”

Apparently pointing a finger at Russ and Assistant U.S. Attorney Heather Rattan, who was leading the criminal inquiry into Walmart, the company’s lawyers said Eastern District prosecutors employed “unethical threats of criminal sanctions meant to leverage a huge civil settlement.”

“Unfortunately, certain DOJ officials have long seemed more focused on chasing headlines than fixing the crisis,” Walmart officials said in a written statement issued Oct. 20, 2020.

Calling Rattan “one of the finest people I’ve met in my entire life,” Russ is dismissive of Walmart’s criticism. “If the best the company can come up with is a one-liner from a settlement negotiation to say someone has bad intent, then God bless them, because that’s not a defense to what happened.”

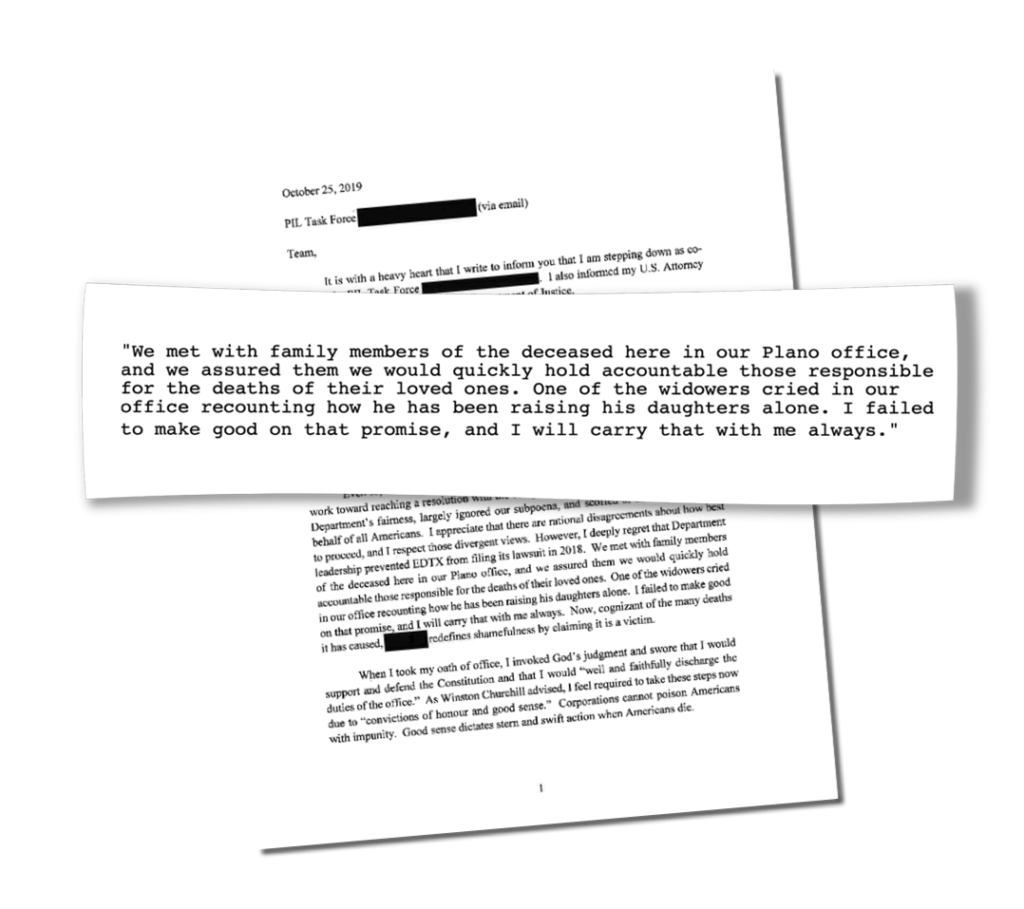

The Resignation Letter

In his resignation letter, now in the public record, Russ cited his personal failure to hold the company accountable, particularly his promise to the families impacted by the crisis in his district.

“We assured them we would quickly hold accountable those responsible for the deaths of their loved ones,” he said in a letter to the team of prosecutors and investigators who had helped him. “I failed to make on that promise, and I will carry that with me always.”

But beyond that personal shortfall was a stinging rebuke of Walmart and the Justice Department officials Russ believed had undermined good-faith efforts to curb the crisis.

It was a strategy — as Russ came to see it — that questioned the motivation and integrity of him and his colleagues; one that struck at his core and the heritage of his beloved grandfather, and from a company he saw as a serial offender with blood on its hands.

In his resignation letter, there was this:

“Corporations cannot poison Americans with impunity. Good sense dictates stern and swift action when Americans die,” Russ wrote.

But also, this:

“Now, cognizant of the many deaths it has caused,” he wrote, “[Walmart] redefines shamefulness by claiming it is a victim.”

***

Russ’ resignation was a surprise to his boss, Joe Brown, then the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Texas. The following day, when Russ announced his resignation to the rest of his DOJ colleagues, some tried to talk him out of it. He was, after all, one of the youngest civil division heads in DOJ history, and he was leading what could be the largest and most important civil case that the federal government has brought against a corporation during a public health crisis in recent decades.

While his role as a whistleblower has not — until now — been made public, his resignation was followed by months of reverberation.

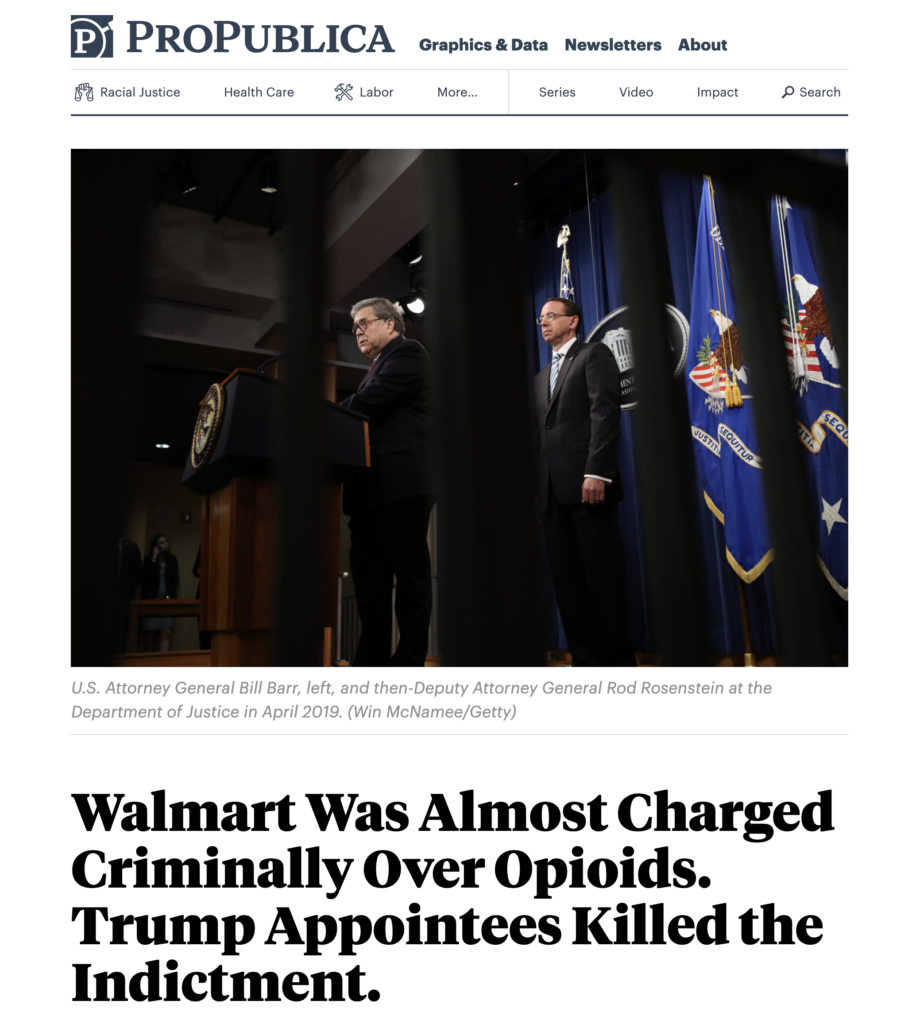

In March 2020, a scathing and authoritative story by Jesse Eisinger and James Bandler about the troubled investigation appeared on the website of ProPublica, a nonprofit investigative news organization. Two months after that, Brown, who was quoted at length in the article, followed Russ into the private sector. Brown declined to speak with The Texas Lawbook for this story.

DOJ officials at the time believed that Russ was the source leaking hundreds of internal Walmart emails and investigative documents to ProPublica — an allegation that Russ told The Texas Lawbook was false. The only thing he admitted to providing was his resignation letter with any mention of “Walmart” redacted — the same version he provided to Congress.

Finally, three days before Christmas last year, after years of investigation and negotiation and on William Barr’s last day as attorney general, federal prosecutors from five offices – but not the Eastern District of Texas – filed a lawsuit in Delaware alleging that Walmart routinely violated the CSA.

Two months later, U.S. District Judge Sean Jordan of Sherman rejected Walmart’s preemptive lawsuit accusing the EDTX prosecutors of misconduct and alleging that higher level DOJ officials had already agreed to drop the case. Walmart has since appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and asked U.S. District Judge Colm F. Connolly of the District of Delaware to dismiss the DOJ’s lawsuit.

Although the Eastern District is not one of the offices actively involved in the DOJ’s suit against the retailing giant, the government’s 160-page petition has the fingerprints of Russ and his former EDTX colleagues all over it.

Russ has been interviewed by congressional investigators and last year was a hair away from giving his whistleblower account before the House Judiciary Committee about the case and his allegations of political interference. Even so, he finds it difficult to identify the emotions that still swirl around his life-changing choice to leave his post and the complaint he left behind with the inspector general.

“It’s not really grief. It’s not really despair. It’s making up your mind to do something that’s really scary and hard,” says Russ. “I couldn’t be in a situation looking like I had signed off on the things that were being done, and that is a heart-wrenching position to be in. I still think about it every single day, and I resigned over a year ago.

“I couldn’t resign without lodging that complaint,” Russ added. “[Simply] walking away wasn’t an option; I had to fix it. Sitting here today, I can’t think of any other decision that was more painful and gut-wrenching.”

Russ declines to talk about specifics of the Walmart case or about the specifics of his whistleblower complaint. But much of that can be found in the public record.

“My blowing the whistle really had very, very little to do with the company itself,” Russ said of Walmart. “It was about the department’s conduct. You expect some bad behavior or gamesmanship from defendants — that’s part of the job. I don’t have hard feelings against the company; I want the DOJ to be running better for the American public.”

Friends, family and business acquaintances say they aren’t surprised that Russ rebelled at a challenge to his integrity.

“Maybe one in 100 have the same type of skills he does, but one in 1,000 who will really put his money where his mouth is,” said Winston & Strawn partner Matt Orwig, a former U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Texas who worked opposite of Russ in a couple cases during Russ’ tenure at the DOJ. “His view upholds the oath. He’s one of those people that you look at and think, ‘Gosh, I wish I would behave the same way in those same circumstances,’ and wonder if you would do it that right. He’s the gold standard.”

“Josh is a phenomenal lawyer because he is smart, dedicated and an excellent writer,” said Joel Reese, a name partner at Reese Marketos, where Russ landed his practice. “But more importantly, he is a great person because he acts without ego or self-interest. He is guided solely by his own moral compass and deep-seated honesty.”

“If he sees something that’s wrong, then he’s going to speak out against it,” said Brian F. “Rusty” Russ Jr., Josh’s father. “He’s not easily intimidated to back off on what his beliefs are, whatever they may be.”

“I think Josh thought he was doing [what] he needed to do to live with himself,” said Bryan F. “Trey” Russ III, Josh’s older brother. “He was sending a broader message that he was not just going to be a puppet.” Those characteristics became important in the making of both Josh Russ the Whistleblower and Josh Russ the Target.

A Family of Lawyers

Josh Russ comes from a family of trial lawyers. His grandfather’s portrait hangs in the Robertson County courthouse in Franklin. Bryan F. Russ served 24 years as county attorney. Josh’s father was recently elected as district judge there. His brother, Trey Russ, represents the third generation of the family to practice at the firm formed in Franklin by his grandfather: Palmos, Russ, McCullough & Russ.

Josh Russ grew up in Robertson County, and folks there still recall his grandfather and the national attention provoked by his 1962 grand jury investigation into the death of Henry Marshall, a U.S. Agriculture Department official who was found dead while investigating legendary swindler Billie Sol Estes.

By the time the elder Russ retired in the 1970s to return to private practice, he had lost count of how many criminal cases he prosecuted. But he was certain about one thing: He never lost a case.

Sometimes a win came by way of courtroom theatrics.

One of Russ’ criminal cases involved the prosecution of a 17-year-old accused of raping a woman at knifepoint. At the end of the sentencing phase, Russ ended a relatively unmemorable closing with a stroll back to his seat. But as he passed the evidence table, he casually picked up the knife from the evidence table and threw it into the defense table, where it stuck and quivered as he finished his argument to the jury.

Bryan F. Russ, Josh’s grandfather

“One more thing. If you decide to give the defendant probation … be sure to send that with him,” Russ said. The jury gave the defendant 20 years.

While it appeared to be a spontaneous at the time, it was later revealed that Russ had practiced in the courthouse the night before by throwing the knife into a piece of plywood on top of the counsel table.

Rusty Russ made a point of exposing his children to the law: taking them into the office and talking about his cases at the breakfast table. Josh recalls being interested in his dad’s cases and wondering why his dad got so many evening calls from clients with plumbing issues (“They relied on him to solve their problems,” he said). When Josh and his siblings argued, his father would hold court in his home office. They would sit in chairs facing their father’s desk and take turns sharing their account of some event, then wait for their father to make a ruling.

“He started using it as a teaching opportunity,” Russ said. “Maybe we didn’t appreciate it as much at the time, but I definitely remember him doing that.”

Sometimes lessons were self-taught. As a 5-year-old in a small town, Russ and his brother Trey were allowed to take their BB guns into the woods, as long as they promised not to shoot at bluebirds. When Trey shot one, Josh helped put it out of its misery, thus sharing the blame with his brother.

“I immediately felt horrible,” says Josh, now 36, recalling the incident.

As the family ate dinner that evening in the den, the day’s events were still eating at Josh. Though the brothers had agreed not to speak of the incident, Josh couldn’t handle the guilt. “Mom, we shot a bluebird,” he confessed.

The punishment was temporary (a BB gun ban for a week or so) but the experience stuck. It is Josh’s earliest memory of the value of truth and rules.

“I like to be able to sleep well at night,” Russ says. “I like to be able to look at myself and be proud of who I am. I like to be able to tell my kids to be honest and know that I’m not asking them to do anything more than what I would expect of myself.”

Coming from a family of basketball players, Russ was a talented player himself, with aspirations to earn a basketball scholarship. But when he was 14, he was diagnosed with a spine condition. He continued to play through three more seasons on the varsity team with pain during every game. He finally underwent a spinal fusion surgery three days after graduating as valedictorian in his class.

“That has had a big impact as far as being able to persevere and dealing with adversity — especially when you’re young and you realize you may not be able to do the things you want to do,” he said. “But it also helped me understand suffering. When you’re in constant pain, it teaches you about your perspective and matures you fast — especially as you’re going through it as a teen — and about having empathy for people.”

Becoming a Lawyer

After graduation from the high school in Franklin, he attended the University of Miami. It was there where he built the foundation for his legal career through his political science and history studies. He also met his wife, Alisha. The couple decided to move to the Bay Area after college so Alisha could attend chiropractic school and Russ could study law at Berkeley. The couple got married after Russ’ first year in law school.

Josh (Center) with his father and grandfather

Russ became intrigued with becoming an assistant U.S. attorney while working as an extern for the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California. He watched two prosecutors try a case against a businessman who had been indicted for soliciting sex with a minor.

“I didn’t know until I watched that trial what an AUSA was or what a federal prosecutor did, but I was intrigued by it,” Russ said. “So, I started making connections with people who were AUSAs and people who were interested in becoming AUSAs.”

After law school, Russ began his legal career in Thompson & Knight’s Dallas office, where he was a corporate lawyer “for like two weeks” before TK partner Wilson Jones took Russ under his wing and he began practicing healthcare litigation and regulatory compliance.

Two-and-a-half years into his career, Jones sent Russ to rural Indiana to lead a small, one-day bench trial involving a physician who owed a debt to a hospital. It was Russ’ first trial, and he was yet to take his first deposition.

Russ said the judge, who had to have been around 70 years old, poked his head in the courtroom and asked, “Is this gonna take long? Because I have some dental work I need to have done.”

“Without missing a beat, I said ‘Absolutely not,’ and tried the case in less than five hours,” Russ said. He won, anyway.

“It was a rush. After that experience, it reminded me why I went to law school: to be in the courtroom, try cases, advocate — everything my grandfather had done.”

After that trial, Russ met lawyers at Reese Gordon Marketos, a Dallas litigation boutique. The firm was looking for a third-year associate. Russ put his name in and got hired in 2013.

Less than a year after arriving at the firm, now called Reese Marketos, Russ experienced what lawyers describe as a Perry Mason moment. He took a deposition in El Paso involving a debt collection matter in which the debtor had lodged a counterclaim. The case involved land, a multimillion-dollar loan and a guarantee made by a bank, and Russ’ client had purchased the loan. The debtor claimed he had made payments that had not been credited to the account.

While preparing a couple of nights before, Russ went through the record of the case and accounted for every penny in the debtor’s claim. When he deposed the debtor’s corporate representative, the official admitted that his counterclaim was not true.

“He glanced over at his lawyer and looked like he was so mad at [him],” Russ recalled.

“It’s false, isn’t it?” Russ asked the witness.

“It’s not true,” the corporate official admitted.

At the end of 2014, Russ learned civil AUSA positions had opened in both the Northern District of Texas and Eastern District of Texas’ Plano division. Russ applied for positions in both districts, went through multiple rounds of interviews and received an offer in the Eastern District after meeting with U.S. Attorney Malcolm Bales in the spring of 2015.

Bales was interested in beefing up EDTX’s civil division because he saw an opportunity for the office to grow its presence on the plaintiff’s side in healthcare fraud and qui tam cases.

Historically, the civil division had focused on defending the government in civil lawsuits such as Social Security cases and bankruptcy matters, but it had not been assertive in pursuing civil fraud.

Bales said Russ immediately impressed him for a few reasons: He had the perfect experience of healthcare law and complex civil litigation needed for the job and had “impressive academic credentials.”

But what was most compelling to Bales was that Russ, unlike most in the office, was actually from East Texas.

“I was intrigued because the guy had gone big in terms of choice of university and going to Berkeley for law school, but his parents still lived in Franklin,” Bales said. “I liked that Josh had East Texas values.”

Russ started in the U.S. attorney’s office in June 2015, and it immediately became apparent to him that he had, indeed, landed his dream job.

The Dream Job

Russ says the best day of his career was the day he took the oath as a federal prosecutor. He printed a copy of the oath and pasted it on the credenza behind his office desk. It was that oath, Russ says, that gave a purpose and a set of values in this everyday work for the Department of Justice.

“I did it with my whole heart,” Russ said. “It wasn’t just a career … to pull a paycheck. It was really driven by doing it right.

“There’s a saying that percolates within the DOJ about how you do the right thing, the right way, for the right reasons,” he said. “The day I took the oath was by far the most important and probably the greatest day of my career.”

(From Left): Then-EDTX U.S. Attorney Joe Brown; Josh’s mother, Laura Russ; Josh Russ; Josh’s wife, Alisha Russ, and Josh’s father, Rusty Russ. In front are the couple’s two sons, Luke and Lawson.

Russ began his time in the Eastern District of Texas as an affirmative civil enforcement (ACE) coordinator, a civil AUSA position within the DOJ that typically handles False Claims Act cases on behalf of the government. The cases usually fall under three categories: health care fraud, procurement fraud and contractor fraud.

Even before Russ joined, the DOJ was moving to beef up “parallel investigations” — collaboration between the civil and criminal divisions (and administrative) on cases that could cross both lines. Over several administrations it was felt that a lack of communication between the civil and criminal sides allowed cases that should have required prosecution, in particular, to slip through the cracks. And even when cases were communicated from one side to the other, they often faced statute of limitations problems before the case could be evaluated.

When Russ came on board, he said there was an “essentially nonexistent policy” on parallel proceedings, so he and a handful of colleagues led the charge in writing the Eastern District’s policies.

Russ said the first year of this endeavor revolved around “relationship and credibility building” among prosecutors across the district.

“Criminal prosecutors are very protective of their cases for good reason; they don’t want something messed up by civil,” Russ said. “So, part of it was gaining their trust that we know what we’re doing.”

Sometimes developing the rapport was as simple as driving to the various divisions within the Eastern District jurisdiction and meeting with criminal prosecutors to “let people know what we could do.”

By May 2016, the Eastern District’s work caught the attention of others within the department, and Russ was asked to speak on a panel at the University of South Carolina’s National Advocacy Center, the facility where DOJ trains its prosecutors.

More speaking engagements followed. He was sent to Germany to present before military personnel who primarily focused on criminal procurement fraud. He guest lectured at the University of Houston Law Center. He talked especially about how parallel proceedings worked with False Claims Act cases and how, through the collaboration of the criminal and civil divisions, it makes it easier to recover more money for the government.

Meanwhile, Russ was practicing what he was preaching in his own jurisdiction.

“Right off the bat” Russ joined an on-going False Claims Act case brought in the Eastern District against the East Texas Medical Center and its ambulance company, Paramedics Plus. A whistleblower alleged they offered kickbacks to several municipal entities the defendants had public utility model ambulance contracts with, including Oklahoma’s Emergency Medical Services Authority.

“What we had found was there was roughly $20 million that had gone from the ambulance company to the authority, which is the wrong direction for the money to go,” Russ said.

Russ and others in EDTX’s civil division joined the qui tam case in early 2017 and settled it in August 2018 for nearly $21 million, which was believed at the time to be the largest health care fraud recovery in EDTX.

Dallas lawyer Sarah Wirskye, one of Russ’ opposing counsel who represented an individual defendant in the case, recalled having a positive experience working with Russ.

“What stood out was even though we were opposite of each other, he always had an open and straightforward line of communication,” she said. “I always felt I could trust him and take him at his word.”

Shortly before the settlement, Russ was promoted to chief of the EDTX civil division. He was 33.

The other side of Russ’ practice involved pursuing civil claims under the Controlled Substances Act, the federal statute that regulates the manufacture and distribution of controlled substances. The CSA in particular is an area of the law that allows for parallel proceedings within the federal government — criminal and civil cases.

Since the Eastern District was crosstraining its lawyers, Russ ended up as second chair in a criminal trial against Habiboola Nimatali, a family doctor charged with selling prescriptions for painkillers to patients without examining them. Nimatali was sentenced to six years of prison, a sentence later reversed on appeal for “improper venue.”

On the civil side, Russ decided to focus more on the Controlled Substance Act cases as a tool to help resolve the opioid crisis. By following larger opioid investigations undertaken by EDTX, Russ learned about pill mill operations, and spent his free time reading books like Dreamland by Sam Quinones and Dopesick by Beth Macy about the opioid crisis and watching 60 Minutes documentaries.

“I started trying to get a better sense for what was happening and how it started, and — even though East Texas wasn’t as bad as some areas like in Appalachia — how to make sure it didn’t get worse,” Russ said.

Russ was able to observe what DEA investigators in his office discovered during their undercover operations in these kinds of cases.

“[The agents would] go around and observe, and all of a sudden, you see lines of people outside the clinic before it opens. Well, that’s a red flag,” Russ said. “A lot of them operate the same way — cash-only practice, they’re basically drug dealers in white coats.”

In other instances, a doctor would change their medical charts and write down “allergies” for a patient so he could prescribe cough medicine with codeine, even though “our undercover [investigators] never said anything about a cough or allergies,” Russ said.

“Fights were breaking out in waiting rooms. These really became criminal hot spots,” Russ said. “It’s hard to imagine that it’s practicing medicine at some point.”

The turning point in his education was the prosecution of two doctors, Howard Diamond and Randall Wade, both of whom were charged in connection with multiple overdose deaths linked to their questionable prescriptions for opioids.

Diamond, in particular, was notorious for prescribing the “Holy Trinity,” a dangerous drug combination comprised of a benzodiazepine, an opioid and a muscle relaxant. In 2016, he prescribed a total of 1.46 million dosage units of hydrocodone, 97% of which were for 10mg tablets, the highest strength available. Diamond’s practice was so egregious he began prescribing for Wade’s patients after Wade was arrested.

The convictions of Wade and Diamond helped put the Eastern District on the map for prosecuting opioid cases and “really gave you a sense that the opioid crisis was here in our backyards,” Russ said.

But the investigation also revealed that an inordinate amount of their prescriptions had been filled by pharmacists at Walmart. A DEA agent testified at Diamond’s 2017 detention hearing, revealing a raid on at least one Walmart pharmacy in East Texas.

Because of Russ’s work developing EDTX’s parallel proceeding policy and educating criminal prosecutors about what the civil division can do, Heather Rattan, the lead prosecutor who criminally investigated Walmart, approached Russ about working in parallel.

“People started seeing what we [the civil department] were doing, and it’s why people like Heather called me and started seeing the value of the civil division and what we could do,” Russ said.

Parallel Proceedings

As the public record now reveals, the DEA and a group of criminal EDTX prosecutors led by Rattan began investigating Walmart in 2016 after investigations of Diamond and Wade were underway. One of the primary issues that concerned the government was the fact that Walmart had continued to fill thousands of suspect opioid prescriptions while still working under a previous agreement not to, according to the DOJ’s lawsuit ultimately filed against Walmart.

In March 2011, Walmart signed a four-year memorandum of agreement with the DEA to avoid administrative actions for a failure of a Walmart pharmacy in California to comply with its CSA obligations. Under the MOA, Walmart agreed it would no longer fill questionable prescriptions and would report any incidents to the DEA within seven days.

In response, the government later charged, Walmart created a system of “red flags” to identify bogus prescriptions from suspected pill mill operations but chose not to disseminate them to its pharmacists. Acting as a wholesaler and a dispenser of the drugs, Walmart was uniquely positioned to help the government interdict their illegal distribution, but instead urged its managers to “drive sales” instead of refusing and reporting fraudulent or excessive opioid prescriptions, the DOJ lawsuit alleges.

The sheer numbers are as heartbreaking as they are staggering. According to the DOJ’s lawsuit, the Centers for Disease Control reported 232,000 deaths from opioid overdoses between 1999 and 2018. In 2016 alone, there were 42,000 opioid overdose deaths, about 16,800 (40%) from prescription sources. The Covid-19 pandemic has not helped. A JAMA Psychiatry study published in February shows that emergency visits related to opioid overdoses were up by 45% between March and October of 2020 compared to that same period in 2019.

Walmart not only continued to fill “red flag” prescriptions but refused to allow its pharmacists — as a matter of company policy — to categorically decline fulfillment of all prescriptions from suspected “pill mill” operations and, in some cases, filling prescriptions from them when other pharmacies, even other Walmart pharmacists, refused, the DOJ lawsuit alleges.

“In doing so, Walmart endangered its customers and contributed to the prescription drug abuse epidemic that has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives,” says the lawsuit.

According to the March 2020 ProPublica article that first broke the news about the EDTX investigation, Walmart filled 13,000 prescriptions for Diamond alone between early 2014 and March 2017 — three months after the DEA raided Walmart. And Walmart only blocked prescriptions written by Wade in November 2016, a month after he was indicted.

A criminal investigation into a publicly traded company is an obviously sensitive matter, often requiring review at the highest levels of the Department of Justice. And as the criminal investigation lost momentum, Russ and the civil team began their own investigation under the relatively new EDTX policy of “parallel proceedings.”

Although later accused, in effect, of being unethically aggressive, Russ says he was, at first, skeptical of making a case against Walmart.

“If you had told me at the beginning of the process where we ended up, I probably wouldn’t have believed you,” Russ told The Texas Lawbook. “Even when we started to follow it, I was still very skeptical, like, ‘This has to be a one-off. It’s got to be a mistake or something.’ We were a very skeptical unit. We weren’t trying to make headlines. We were trying to just follow the evidence — and really trying to protect the public.”

Following a document production by Walmart, Russ got into the weeds. Russ declines to speak in specifics about what he found, but suffice it to say it was apparently enough to return the case to Rattan and her staff on the criminal side.

“I grew a beard because I was so in it,” he said. “I went through document by document to figure out what happened.”

According to ProPublica’s report, Rattan informed Walmart in the spring of 2018 that she was preparing to indict the company for violating the Controlled Substances Act. Walmart requested a meeting, and both sides met in April 2018. The meeting between prosecutors and Walmart’s attorneys apparently began politely, only to be soiled by the word “embarrass.”

There’s a dispute between two sides over the specifics of context.

In Walmart’s version, the ProPublica report says, Rattan said she aimed to “embarrass Walmart” with a criminal indictment. Rattan’s version is that she told the Walmart reps that the company should feel “embarrassed” by its conduct.

Walmart asked for 30 days to respond, and the parties gathered again for a two-day meeting in early May 2018 in EDTX’s Plano office — this time with Russ and others from the civil division in attendance, the report says. Russ hadn’t planned to attend because the meeting was being led by the criminal side.

There was more than courtesy involved. There was also a policy consideration. Under Justice Department policy, backed by substantial case law, criminal and civil actions can be coordinated, so long as they are not used to leverage each other. A civil suit, for instance, should not be filed solely to develop evidence for a criminal case. And conversely, a criminal prosecution should not be used to leverage a larger civil settlement. But Walmart, apparently seeking a more universal agreement, asked in writing that Russ attend, according to the ProPublica report.

Walmart’s lawyers, led by Jones Day partner and former U.S. Attorney Karen Hewitt of San Diego and Walmart Chief Counsel of Global Investigations Bob Balfe, former U.S. attorney for the Western District of Arkansas, spent the first six hours presenting the results of the company’s own internal investigation. Jones Day lawyers in Dallas also represented Walmart when the retailer was investigated by the DOJ and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission in 2012 for possible violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

The Jones Day internal investigation concluded that there had been no criminal wrongdoing by Walmart or any of its employees, according to the ProPublica report. The investigation had also found no evidence of collusion or any improper financial relationships between doctors or customers and Walmart pharmacists.

According to DOJ court filings, this conflicted directly with a vast amount of evidence compiled from Walmart’s own records, as well as direct email communications from a Walmart manager describing a company policy not to cut off fulfillment for suspected pill mills and, finally, not to report bogus prescriptions as agreed to under the 2011 MOA.

The threat of criminal indictment, however, clearly drove the negotiations. As described by ProPublica, Walmart’s lawyers explained to the prosecutors the risks to shareholders, employees and the public that could stem from a criminal prosecution. The AUSAs remained unconvinced, likening those arguments to an individual defendant who says the prosecution would hurt his or her children. Plus, just because Walmart was big and powerful didn’t mean that it was immune from a prosecution.

According to ProPublica, lawyers for Walmart asked Russ to be a part of a meeting with prosecutors. But his presence at the meeting later became part of the Walmart defense.

The DOJ lawyers’ takeaway from Walmart’s tone of the first day was that Walmart hadn’t done anything wrong and that it didn’t need to take the prosecutors seriously — a sentiment that seemed corroborated the following day when Walmart, which rakes in approximately $500 billion in annual revenue, offered to settle for $34 million, according to the ProPublica report. By contrast, several state attorneys general recently reached a $26 billion settlement with the nation’s three largest distributors and drugmaker Johnson & Johnson for their role in the opioid crisis, and it is believed that local governments will turn their attention to major pharmacies next.

According to the report, Russ called the offer “insulting” and said they could do better. Walmart accused the prosecutors of trying to leverage the threat of a criminal prosecution for a higher civil settlement. Feeling that his moral compass had been attacked, Russ left the room.

A week after the meetings, Hewitt wrote to then-U.S. Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, accusing the EDTX prosecutors of ethical violations, the report says. Walmart, by its own admission, decided to stop cooperating with the government’s investigation because of those alleged ethical violations, despite Walmart now contending that it has been cooperating since the beginning, the public record shows.

Russ made it clear in his interviews with The Lawbook that he wasn’t looking for a settlement; he wanted a lawsuit. With the criminal investigation now hanging by a thread, Russ ramped up the civil effort. By August 2018, Russ and others in EDTX’s civil division were ready to file their complaint and the U.S. attorney’s office began preparing for a press conference to announce the civil charges, the ProPublica report says.

That same month, Hewitt wrote to Brian Benczkowski, the head of the DOJ’s criminal division. Hewitt’s letter said that a conviction against Walmart could harm millions of low-income elderly citizens who rely on welfare for food and medicine because a conviction would jeopardize Walmart’s ability to participate in those federal programs.

Soon after, an official in the deputy attorney general’s office called Joe Brown and ordered him to halt the criminal investigation, the ProPublica report says.

“The Justice Department’s investigation of Walmart was riddled with misconduct and it ended with the Department filing an unjustified lawsuit in which it invented legal theories out of whole cloth to try to extract a massive payment from the company,” Walmart spokesperson Randy Hargrove said in a statement provided to The Texas Lawbook. “If that’s special treatment, we can only wonder what the alternative is.”

In response to a list of questions The Lawbook sent, Walmart referred to the full statement it provided to ProPublica for its article and a number of documents in the public record that reflect its positions for why the corporation thought the prosecutors engaged in misconduct and how it views the responsibilities of its pharmacists.

Walmart is still pursuing their lawsuit against the Justice Department before the U.S. Fifth Circuit

For example, in a Sept. 27, 2019 letter addressed to Gustav Eyler, the director of the DOJ’s consumer protection branch, Hewitt noted a meeting a week earlier between Russ, Rattan and Mike Gibson, the attorney for Brad Nelson, a former Walmart employee from the compliance department who the DOJ’s criminal division sought to indict individually.

The letter stated Walmart was “deeply concerned” that Russ participated in that meeting, and that his participation “raises serious concerns regarding the current demands of the” working group (the group of 15 U.S. attorney’s offices on the Walmart investigation).

Russ called this misconduct allegation “hypocritical” in light of the May 2018 meeting between Walmart and both criminal and civil divisions that the company begged Russ attend. He said the meeting with Gibson, who he called a “seasoned criminal defense lawyer,” was conducted “appropriately” and “followed all guidelines and best practices” consistent with parallel proceedings, and that Gibson said he was comfortable meeting with Russ and Rattan together when they asked him whether he would prefer to meet with them separately or together.

“This behavior was clearly improper, violated the Department of Justice’s own internal policies and rules of legal ethics, and was entirely inconsistent with the Department’s long-standing policies,” Walmart’s 475-word statement to ProPublica said. “We only asked that the Department of Justice give us a fair hearing, that the prosecutors conduct themselves ethically, and that any baseless criminal investigation be closed, as required by the proper application of the law.

“We are proud of our pharmacists and compliance experts who continue to serve the best interests of our customers despite complex and often conflicting direction from federal and state regulators and prescribers,” the statement continues. “We will continue to combat opioid misuse and abuse through our industry-leading efforts, which go far beyond anything required by law.”

On the civil side, Deputy Associate Attorney General Steve Cox began to push back on the civil case, saying the case wasn’t ready, according to the ProPublica report.

Adding to the controversy, Cox was appointed U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Texas in May 2020. Some EDTX prosecutors believed Barr sent Cox to Texas because he opposed the litigation against Walmart.

Cox declined to comment for this article, but he rejected that argument in an interview with The Texas Lawbook in January 2021, when he resigned to return to the private sector.

“I couldn’t comment on any pending litigation, but my role in any case while I was in the associate AG’s office was to do all I could to drive it forward to a successful and just result, and that case was no different,” Cox told The Texas Lawbook.

Main Justice in late summer 2018 ordered a six-month cooling off period in EDTX and told the prosecutors to try to settle. In addition, efforts to secure subpoenas to further clarify what Walmart’s top officials knew were blocked by officials in Washington, the ProPublica report says.

Russ began recruiting prosecutors from other U.S. attorney offices around the country to help him with the case. He particularly praised four offices that now appear on the docket for the DOJ’s lawsuit against Walmart: the District of Colorado, the Middle District of Florida, the Eastern District of New York and the Eastern District of North Carolina.

“The Eastern District of New York has one of the most preeminent civil Controlled Substance Act attorneys in the world who teaches on this and teaches other AUSA’s,” Russ told The Lawbook. He described the lawyers in Florida as “standup,” an AUSA in Colorado as being behind some of the largest CSA settlements in the nation and the Eastern District of North Carolina as “amazing.”

“These people put a ton of time and … time away from their family to work on something that I felt — and they shared — was a really important case because they wanted to save lives too.”

So, when one example after another of political interference followed in the last year of Russ’ career at the DOJ that continued to delay the filing of the case, it weighed on Russ incrementally.

“I felt like I had to do something so they could do their jobs.”

Resignation and Complaint

Russ said it was a combination of the filing delays and an internally imposed block from gathering key evidence — both of which he believes were driven by special treatment — that finally led him to the decision to resign.

As the end of the six-month cooling off period approached, in mid-2019, Russ reported to Washington that Walmart was still not cooperating, the ProPublica report said. Trump officials decided to give Walmart three more months. And as that deadline approached on Oct. 25, DOJ officials decided to give Walmart another extension in negotiations.

Russ had had it.

Russ called Joel Reese the evening of Oct. 23 and told him that something might happen that shouldn’t, and if it did, he would need to resign. The thing happened.

Russ and Reese looked at offices together in Plano the following day.

“We were meeting the victims’ families and we told them we were going to take action, so this is not a case that was covert,” Russ told The Texas Lawbook. “It’s not a case that a company didn’t know they were under investigation; they did for years. Fast forward to a year-and-a-half after those victims were told we are going to do something, and we’re being handcuffed by political appointees and not being able to do anything. It echoed to me that I am not going to be in a position where I re-victimize these families because of politics.”

“I wanted to do my job. I wanted to do my cases. I was civil chief at 33,” he said. “I thought there was a good chance I could potentially even become U.S. Attorney down the road just by doing the right thing. This was the first time in my life that I felt like doing the right thing resulted in me having to resign.”

Some may wonder why Russ resigned since, after all was said and done, the DOJ still ended up charging Walmart on the civil side. To that, Russ replies that his main reasons for leaving did not have much to do with the Walmart case itself, but the realization that “something is institutionally wrong with the department.”

Main Justice’s interference in collecting “key evidence core to the case was the last straw for me,” Russ said. “I had never seen that in an investigation.”

It was not simply a matter of Main Justice wanting to wait until the right time to file a lawsuit and Russ got impatient because that argument did not “square away with what was being said and happening at the time,” Russ said.

“There were delays for all sorts of reasons that kept changing,” he said. “I was saying, ‘If we’re going to keep investigating, let’s get the key information.’ I was trying to do what Main Justice wanted but I wasn’t able to do the key investigation. But in the meantime, people were dying.”

That last point, Russ says, is precisely why the case needed to land in court sooner than later.

“I trust courts and I trust juries. They’re there for a reason,” Russ said. “I think our DOJ lawyers ought to trust judges and the process and not be allowed for this to be played out in a secret arena.

“There are some cases where a settlement is completely appropriate, and others where people deserve complete transparency. An opioid crisis is one where I believe the public deserves full transparency.

“I felt a sense of urgency and a responsibility that every day that ticked by, some other pharmacy somewhere was allowing the same thing to happen and that we had to act quickly to deter that,” he added. “Not necessarily this defendant, but all other defendants. Which is why you do cases: to deter. In this case, deterrence didn’t mean saving a few million dollars from the Medicare trust; it meant saving lives.”

(From left) James Crowell IV, Dir. of Executive Office of US Attorneys, with Deputy Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen, Josh Russ and EDTX U.S. Attorney Joe Brown, in Washington in 2019 as Josh was being recognized for superior performance as an AUSA in the Civil Section.

Russ said during his last year at the DOJ, he carried around a 6×8 notebook that he used to jot down tasks and thoughts related to his duties as civil chief as well as notes on matters on his caseload. But he also filled part of the notebook with his notes on dates and conversations “on things that were odd, not normal or concerning” with respect to internal DOJ dealings related to the Walmart case.

In “broad strokes,” Russ said these strange things involved “serious revolving door issues” between the DOJ and corporations, what the public was being told about certain opioid programs versus what was happening internally, and the involvement of particular U.S. Attorney offices that had not previously been involved in controlled substances cases that “shouldn’t be” due to “the appearance of impropriety” and “revolving door issues.”

“I started to jot [it all] down — not that I really needed it because it was so stunning [that] I memorized it,” Russ said.

But before resigning and filing his complaint, Russ made sure his observations of political interference in the Walmart case were not just guesswork and not in a vacuum. He asked around. Many validated his observations.

Russ said he was told by one seasoned prosecutor who “grew up in the department” that the Walmart case was “unprecedented” and “the worst case of special access [they] had ever seen.”

“I was testing assumptions and testing what I saw and getting confirmation on things that were said or done, because you don’t want to do something you don’t have to do,” Russ said. “It’s painful. It’s like trying to come up with a reason not to pull out stitches.”

By the time Russ announced his resignation to his colleagues, Russ had already written up most of his whistleblower complaint. He finished his resignation letter midmorning of Oct. 25, 2019, added what was left to add in his complaint. Then he quietly printed everything out and asked his assistant to FedEx the complaint to the inspector general. He sent his letter to his group, and his office phone and cellphone “immediately started blowing up.”

On Russ’s last day in the U.S. attorney’s office, he left an Eisenhower quote on the whiteboard in his office:

“A people that values its privileges above its principles soon loses both.”

***

Several months after he shipped off his whistleblower complaint, Russ hired David Seide, a lawyer in Washington, D.C., for the whistleblower advocacy organization, the Government Accountability Project, to help him navigate his dealings with the OIG and Congress.

Dating back to 1977, the Government Accountability Project originated from the Institute of Policy Studies and its dealings with Pentagon Papers whistleblowers. Seide has a track record of representing high-profile whistleblowers and, as a former federal prosecutor himself, is particularly active in working with whistleblowers from the Justice Department. Russ’s law partners, Joel Reese and Brett Rosenthal, are also on his legal team.

“[Josh’s] case is important because it’s all about the opioid crisis and participants who enabled it,” Seide said. “It’s fair to say that it wasn’t just the manufacturers of the products that have some responsibility, but it’s everyone else who participates in the distribution of narcotics throughout the system.”

Josh Russ with Joel Reese

Russ said he actually got in touch with the House Judiciary Committee before he retained Seide because in early 2020 he started seeing concerning news reports that indicated widespread improper political influence across the department. One large example was the DOJ’s plans to reduce Trump ally Roger Stone’s sentence, which led the entire team of criminal prosecutors on the case to resign.

“I didn’t know if I had done enough as an officer of court to prevent what could be improper influence on a case that is supposed to be representing America’s interest,” Russ said. “I found a way to get in touch with the House Judiciary Committee to let them know my concerns because they have oversight and investigative authority over what the executive branch was doing, and they were very interested.”

Russ was scheduled to testify before Congress, but because of the Covid-19 pandemic and other delays, it never happened. But Russ said his experience with Congress was positive.

“They took it seriously, they asked questions, and they wanted to get to the bottom of it,” he said. “They started sending letters around … they wanted explanations. I’m not sure they ever got them, but at least there were appropriate eyes on the public’s business.”

Although Russ and Seide have not heard any news about his complaint, Russ said he hopes that him coming forward encourages a second look at his complaint.

“I absolutely hope the Biden administration or Congress or anybody else has the interest in getting to the bottom of it and has a look at it,” he said.

Russ can only speculate whether his whistleblower complaint helped a civil lawsuit against Walmart by the DOJ to come to fruition. But he views the DOJ moving forward with that as a silver lining.

“I’m immensely proud of what [the team of prosecutors on the case] is doing because I think it’s going to save lives, improve policies across the country and improve compliance,” Russ said.

A Whistleblower’s Whistleblower

At Reese Marketos, Russ’s private practice comes full circle with his former and current identities as a prosecutor and whistleblower. After rejoining the firm in November 2019 as a partner, Russ helped start the firm’s new Plano office and leads Reese Marketos’ qui tam and False Claims Act practice group, representing relators — another name for qui tam whistleblowers — in some of the same types of healthcare fraud and defense procurement fraud cases Russ handled as an AUSA. And sometimes he gets to work closely with U.S. Attorney offices around the country.

“I like to think that we’re still wearing the white hat and going after bad actors and trying to get money back for the United States,” Russ said. “Even though I’m wearing a different hat now, it’s still a joy doing that work.”

Currently, he’s representing a whistleblower from JPS Health Network, Fort Worth’s hospital system, who alleges in Fort Worth federal court that the hospital submitted false claims to Medicare, TRICARE and Medicaid.

In September, Russ is slated to head to trial in Alabama federal court on behalf of two whistleblowers who allege MD Helicopters violated the False Claims Act when it negotiated helicopter sales with the U.S. Army. The litigation, ongoing since 2013, has already led to the conviction of a U.S. Army colonel, and also involves businesswoman Lynn Tilton, whose investment firm Patriarch Partners includes MD.

“I feel I may have hit the perfect calling — to use what I went through to give these whistleblowers a real voice and a real chance to take on powerful forces,” Russ said. “The people we represent are amazing people. Some have their whole careers ahead of them, but they just can’t live with themselves. They view it as … the patriotic thing to alert authorities to wrongdoing.”