HOUSTON – Closing arguments concluded Friday afternoon in the Jack Stephen Pursley federal tax evasion trial, but the case will proceed without a juror who the judge has dismissed because the juror apparently flashed a middle finger to others in the courtroom and used the F-word in response to testimony.

U.S. District Judge Lynn Hughes told lawyers Friday morning that he decided to strike Juror No. 5 prior to closing arguments because the juror has been animated throughout the trial and because prosecutors worried that he would cause problems when the jury begins deliberations.

Shortly after closings concluded, Judge Hughes dismissed Juror No. 5 and one of the true alternate jurors, framing it as “random selection.”

“We’re not mad at you,” he said, as Juror No. 5 scuttled out of the courtroom hurriedly.

Juror No. 4, prosecutors pointed out, has appeared annoyed at Juror No. 5.

“Shooting people the middle finger is probably not conducive to deliberation,” Judge Hughes said to the lawyers during the impromptu hearing before the lunch hour. “I didn’t even know what that was until my law clerk explained it.”

“My concern is not that he favors IRS or Pursley, but that he’ll be erratic and mess the whole thing up,” Judge Hughes said. “He could hang the jury.”

In addition to flipping the bird, prosecutors added during the hearing, the juror waved his hands and muttered, “What the fuck?!” Thursday when DOJ lawyer Jack Morgan was cross-examining the defense’s expert witness and cracked a joke on whether the witness would report the income he earned for testifying on his taxes.

While the juror has not indicated which side he favors and has been animated during testimony for both sides, DOJ Prosecutor Sean Beaty noted based on his experience as a former police officer that he knows problematic body language when he sees it.

“I see conflicts coming,” Beaty said to Judge Hughes before he made his ruling.

Victor Vital, who represents Pursley, had a different perspective.

“None of the other 13 [jurors] have complained about him being disruptive,” he said during the impromptu hearing. “Everybody’s talking on observations based on their own interpretations. None of the seated jurors have brought the issue … [on] the record.”

Vital added that the juror was reacting to the evidence as anyone would: “As human beings, they’re going to have emotions,” he said.

Seth Kretzer, who is serving as appellate counsel on the defense team, said that case law does not suggest that Juror No. 5’s behavior constituted juror misconduct.

After Judge Hughes announced he agreed with the government, Vital thanked him for hearing his objections.

“I just want to make sure that when I get to the Fifth Circuit that it’s preserved,” he said.

Despite the unusual twist in the trial, legal experts agree that Judge Hughes’ discretion to strike the juror was justified.

“I don’t see this as reversible error,” said Houston criminal defense lawyer Kent Schaffer. “It is not uncommon for jurors to be struck during trial or even deliberations if the court believes that the juror is potentially disruptive, refusing to deliberate, etc…. Flipping the bird is not something that I have encountered in a case, but I think that the court can find that this type of erratic behavior could indicate that the juror is potentially causing a disruption that could impede the jury process.”

Winston & Strawn’s Tom Melsheimer, who just successfully got the only doctor acquitted from the Forest Park federal bribery and kickback trial, had a slightly different perspective.

“I’ve never heard of what you describe,” he said. “The defense makes a strong point that the juror is entitled, within reason, to have reactions to the evidence. It certainly doesn’t look good for the government to seek to have a juror removed. After all, the prosecution wants to bring cases that are so strong that any 12 Americans would be acceptable to them.

“That said, it is probably within the judge’s wide discretion to remove a juror for misbehavior,” Melsheimer said.

Natalie Posgate is in the courtroom and will provide updates on closing arguments later today.

Day Three: The Man From Rio; A call to Dubai; The existential question

HOUSTON – By Thursday afternoon, when the prosecution rested its tax evasion case against Houston lawyer Jack Stephen Pursley, the jury had been presented with at least three continents from which to draw evidence.

A Brazilian oil rig safety advisor had flown from Rio de Janeiro to testify. A financial crimes enforcement expert from the Isle of Man had testified by video. And the jury was left to contemplate why anyone with $18 million dollars to his name might be working on an African oil rig.

First, the Brazilian.

Eduard Venerabile, the oil rig safety advisor whose name is at the nexus of an alleged $18 million tax avoidance scheme, took the witness stand Thursday morning. And by the time of the first jury break, he confirmed for the prosecution that he has never owned, invested in, or held a bank account on behalf of the many companies involved in the tax evasion scheme – whether they bore his name, or not.

Speaking in a short, staccato English, his answers were one-worded and emphatically redundant — “no,” “never,” “nothing.”

Significantly, he said he never owned Southeastern Shipping, the original source of the repatriated revenues, though he was listed as its legal owner in the company’s incorporation in the Isle of Man.

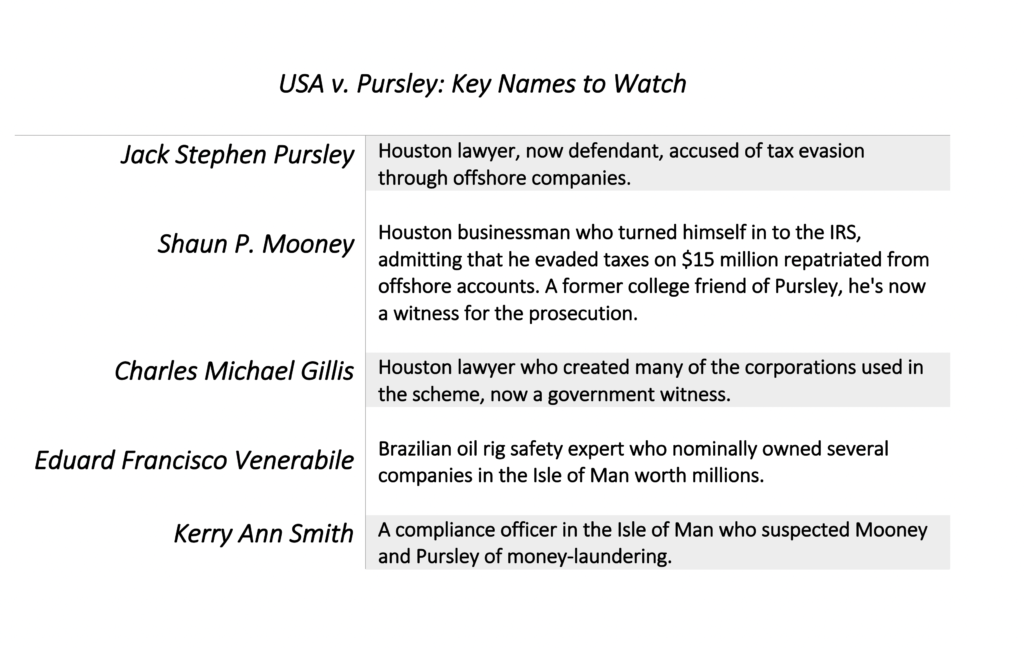

Pursley is accused of helping Houston businessman Shaun P. Mooney repatriate millions from the company through a series of false business loans and bogus investments in shell corporations, for which he received $4.825 million on which taxes were never paid.

The actual ownership of Southeastern Shipping, and the extent to which Mooney’s involvement was known to Pursley and others, is central to the case both for and against the Houston lawyer. Pursley maintains he didn’t know that Mooney owned the company, but records have emerged in the case that suggest he should have.

That perception is important because it was revenues from Southeastern’s offshore rig recruiting business that flowed through a series of companies, properties and investment funds that became part of the alleged tax evasion scheme.

Venerabile said he never met Pursley until 2008, when Pursley traveled to Rio de Janeiro. He recalled a day in 2009, when Pursley came to his house to have him sign documents. There were several. Venerabile said he asked Pursley if he needed a lawyer, and Pursley replied, no; that he, Pursley, was Venerabile’s lawyer.

When prosecutor Jack Morgan asked what he thought of that, Venerabile replied that he didn’t review the documents closely because they included legal language that he didn’t understand. He said his basic belief was that they related to a headhunter operation he was developing within Mooney’s oil rig recruiting business. He signed them anyway – though he noticed that his name was misspelled in several places.

Why would he do that?

“I trusted Mr. Pursley because Mr. Mooney asked me to trust him because he’s a lawyer. Why wouldn’t, I?”

At one point, Venerabile was presented with an email he sent to Pursley in 2012. The Brazilian oil rig safety advisor, nominal owner of a multi-million dollar company, was asking to borrow money for a business plan he had pitched to Pursley and Mooney. Venerabile said he asked them for the funds because interest rates in Brazilian banks were very high at the time.

Morgan pointed out that he emailed the pitch to Pursley, not Mooney.

“But they’re in the same office, huh?” Venerable volunteered.

When Morgan asked why he didn’t take money from Southeastern Shipping, Venerabile said, “What money? I don’t have no money there.”

Wrapping up, Morgan asked Venerabile if he would still be working on oil rigs in Africa if he had the $18 million Southeastern that had been his in the records.

He laughed: “No, never. Do you have any idea of what it’s like to work abroad on African rigs?”

On cross examination by Pursley’s lawyer, Victor Vital, Venerabile’s recollections didn’t jibe completely with the testimony of others. His answers reverted to staccato.

He remembered an August 2001 soirée in Brazil with the Mooney brothers, Shaun and Steve. It was Steve’s bachelor party and he didn’t remember signing documents presented to him, moving Southeastern Shipping from Panama to the Isle of Man.

There was a meeting at the home of a Houston tax lawyer, but he didn’t “remember anything formal” – only dinner and a drink.

Likewise, he remembered a visit by Pursley and Mooney to his worksite in Dubai, but not a phone call with a compliance officer in the Isle of Man who had become suspicious about his alleged ownership of Southeastern Shipping; this, despite earlier testimony that included a handwritten script he had been given in an alleged effort to allay her suspicions.

The compliance officer, Kerry Smith, was a problem for everyone, including her colleagues who managed the Southeastern Shipping account at the Isle of Man Financial Trust.

Appearing before the jury in a video deposition under an immunity agreement with the government, Smith said she had deep-seeded problems with the fact that Venerabile had no operational contact with his own multimillion-dollar account.

She told the court that her suspicion was that the account was either being used for money-laundering, or that Pursley and Mooney were taking control of funds that rightly belonged to Venerabile. At the time, Southeastern Shipping was the firm’s largest client, and her colleagues, especially the account managers, were not inclined to share her suspicions.

“I had a small doubt as to whether he existed based on the lack of information and input he had in relation to the file,” Smith told jurors. “It was key that I established whether he did or not.”

Smith said the telephone conversation with Venerabile in Dubai did not resolve her suspicions. It was not until she met him in the Bahamas – on a trip arranged by Pursley and Mooney – that she became satisfied, if not convinced, that Venerabile owned Southeastern Shipping.

The government closed its case with its expert witness, Michael Frazier, who followed the money — and tax returns — of Pursley.

He narrated the convoluted web of money for jurors, showing how the $4.8 million Pursley received ended up in Pursley’s personal bank accounts. He compared those funds with Pursley’s tax returns for 2007-2010, showing that the funds had never been reported as personal income.

On cross, Vital asked Frazier if he considered a movement of money from one’s right pocket to one’s left pocket a transaction instead of a transfer. Frazier said he didn’t. Pressing further, Vital asked whether looking at paper transfers alone demonstrates what was intended, believed or advised on. Frazier said no.

As the prosecution rested, the defense countered with its own expert witness, Ron Braver, a former IRS agent. But Braver focused on the flow of Mooney’s money and tax returns – not Pursley’s. Judge Lynn N. Hughes interrupted.

“This is completely pointless… we’re not trying Mr. Mooney. Everybody knows that,” Judge Hughes blurted. “So we need to move on to something that provides a defense.”

The defense case resumes Friday.

Day Two: A sin of omission; a Brazilian connection; a judge’s help

HOUSTON – By any measure, Wednesday was a rough day for the government’s key witness in the Jack Pursley tax evasion trial.

Houston businessman Shaun P. Mooney spent most of the day explaining to the jury that he actually owned what he didn’t own; that he’s cheated on his taxes for decades; that his friend was no longer his friend and, finally, that he is now telling the truth about lying to the government at the very moment he had finally chosen to come clean.

That last confession was telling. It came in late afternoon on cross-examination, when Pursley lawyer Nicole LeBoeuf asked Mooney about sworn testimony he had given in a lawsuit between the two. When asked under oath in November 2015 if Pursley had done anything dishonest or unethical, Mooney had mentioned nothing about the elaborate tax evasion scheme he had been testifying about all day Wednesday.

As LeBoeuf pointed out that Mooney’s 2015 testimony had come a full year-and-a-half after he had reported the scheme to the government, Judge Lynn N. Hughes interrupted, advising Mooney “to think hard” before giving an answer.

“If you answered that question truthfully, it would have implicated you. You weren’t keen to do that… you lied to prevent doing that. That’s just the straightforward explanation,” Judge Hughes continued.

“Yes,” Mooney replied.

Earlier in the day, under questioning by prosecutors, Mooney had been far more brazen – both in substance and in tone. Describing for the jury the guiding principle behind his partnership with Pursley, he was blunt: “I didn’t wanna pay my taxes.”

Pursley is accused of helping Mooney repatriate more than $18 million from a lucrative offshore oil rig recruitment company. In exchange, the government contends, Pursley received nearly $4.825 million upon which he paid no taxes.

“I’m not going to say I’m not responsible for what I did,” Mooney said, but Pursley was “heavily involved… he was a central figure in moving the money.”

Because the offshore company, Southeastern Shipping, had become wildly successful —with clients like Noble Drilling — Mooney said he wanted to get the money to the U.S.

“I had money overseas that I didn’t know what to do with… I’m a pretty good businessman, I work hard. But I couldn’t spend it. [Pursley] said, ‘I know what to do with it.’ He told me he had a plan.”

That plan, according to the government, was to repatriate the millions through a complex scheme to avoid paying U.S. taxes.

With Pursley acting as his attorney, the two are accused of setting up a complex network of companies and partnerships designed to hide the Southeastern income as business loans and investments. Mooney’s own interest in Southeastern was disguised through an owner-nominee, a Brazilian offshore rig safety advisor, Eduard F. Venerabile.

Asked about Venerabile’s participation by Justice Department prosecutor Sean Beaty, Mooney became emotional. They had been friends since the 1990s, having met while Mooney was living in Brazil.

Mooney said he went to Venerabile’s house and asked him to help him because he needed to conceal his identity as the owner of Southeastern Shipping.

“I feel bad. Eduard is my friend, and I feel like I used him. I needed a nominee.”

Because Mooney had helped Venerabile get a job a number of years back, Mooney said, “He said you’ve helped me; so, I’ll help you.”

Despite his help, Mooney said Venerabile never had access to the bank accounts in the Isle of Man, where the company eventually moved its incorporation.

Like other witnesses, Mooney is testifying under a non-prosecution agreement with the government.

Pursley has accused Mooney of sparking the federal tax case following a dispute between the two men over money. According to court records, Mooney avoided prosecution and civil action when he reported receiving more than $15 million in offshore funds through the Offshore Volunteer Disclosure Program – a government program that provides prosecutorial leniency in exchange for full disclosure.

As part of the ensuing agreement, Mooney testified that he has since paid the government nearly $10 million in back taxes.

Mooney depicted for the jury what he characterized as a very close working relationship with Pursley. Mooney said the two had stayed in touch after their college years at Texas Christian University and at one point Pursley stayed with Mooney when he lived in Brazil. They had gone on trips together, including to Australia and even officed together for a time, Mooney said.

But more significantly, Mooney told the court that no one other than Pursley knew that he had avoided paying taxes on Southeastern Shipping ever since he had incorporated it.

Mooney said his relationship with Pursley ultimately deteriorated over money. From his point of view, Pursley was getting greedy. After Pursley agreed to help him evade his taxes, Pursley still wanted more. In addition to the $4.8 million he demanded, Mooney said, he asked him for a 40% stake in his offshore staffing business.

“I walked out [of the meeting] and said this is ridiculous,” Mooney said.

He ultimately agreed to give him a 25% stake in the business. “I felt like I was really stuck,” he explained. “I would have liked to have gotten it down to zero… I regarded it as a legal fee.”

“I made a horrible decision,” Mooney said. “I was really, really scared about everything I had done… I made some ridiculously bad decisions.”

The government showed the document that, according to Mooney, Pursley had drafted up reflecting this agreement. It was framed as an investment, but Mooney said it was really a fee.

By the end of 2012, Mooney said, the relationship had completely deteriorated. Pursley still wanted more, he said. He emailed his brother and his brother’s law partner, asking for advice on how to rid himself of Pursley.

“He just wanted more by doing nothing,” Mooney told the jury. “I was the rainmaker, I was killing myself… he wasn’t doing anything but chasing a check.”

When Beaty asked him if they were still friends, Mooney replied, “there’s no friendship there.” Asked if he could recall the last time he saw Pursley socially, Mooney paused: “I just don’t remember. It’s been a while.”

Once the funds from Southeastern Shipping got to the U.S., Mooney said he bought a house in Edwards, Colorado. He said that Pursley advised him to draft up a promissory note from Mooney’s company, Diversified Land Holdings, that loaned money to him. He said Pursley said the purpose was to continue hiding the funds.”

“[We did it] to keep the scheme going,” Mooney said. “To hide funds, to not pay taxes. He told me it was important to keep up.”

Beaty asked Mooney how many people he had lied to over the years. In general, Mooney said he had been using foreign corporations to cheat on his tax returns since 1990 or 1991. It was about then, he said, that he first opened an account with BSI, a bank on the Switzerland-Italy border that he used while he was living and working in Brazil.

On a screen in the courtroom, Beaty pulled up a 2005 document from the financial advisors KPMG. The document described Mooney as the owner of Southeastern Shipping. Mooney said the document was created after he got in touch with the Isle of Man Financial Trust to figure out how he could move his money to the U.S.

He said Pursley had a copy of it because he personally handed him a copy.

On cross examination, LaBoeuf attempted to establish that, despite his decision to confess to the government, much of what he has told them – and the jury – is in conflict.

For instance, LeBoeuf pulled up that 2005 KPMG memo, which had been part of a package prepared for Nigel Tibay, a financial advisor in the Isle of Man. She pointed out, and Mooney confirmed, that a disclaimer marked the memo “for discussion purposes only” and “tentative purposes.”

LeBoeuf pointed out that Mooney had sought yet another opinion on the topic two years later by a firm in London called International Fiscal Services Limited. She pointed out that the new memo offered yet another opinion: that Southeastern Shipping was owned by Eduard Venerabile.

Mooney’s reaction was defensive: “The fact was I was banking in an overseas jurisdiction, and I didn’t want my name known. I was very clear about that. I used a nominee so I wouldn’t be identified. That was the fact.”

LeBoeuf challenged Mooney’s recollections on a variety of issues about time and money. She pointed out that Mooney, not Pursley, had moved Southeastern Shipping from Panama to the Isle of Man; that Mooney, not Pursley, had installed Venerabile as the company’s nominal owner.

She pointed out that Pursley had only recently received his law degree when Mooney says Pursley helped him create the highly complex tax evasion scheme.

“That’s not something I keep up with,” was Mooney’s reply.

Day One: One jury in 25 minutes; Two opening arguments before lunch; Three Houston lawyers tell the jury what they know

HOUSTON – Jury selection began early Tuesday morning in federal court for Jack Stephen Pursley, a Houston lawyer accused of tax evasion by the federal government. It ended just 25 minutes later.

By the lunch break, both sides had made their opening statements. By day’s end four witnesses had testified – three Houston lawyers and a homeowner who lives near Pursley’s Colorado ski home.

Cases move briskly in District Judge Lynn N. Hughes’ court.

Pursley is accused of helping his client and business partner in an overseas oil rig recruiting venture repatriate $18 million from the company in personal income disguised as investments and business loans. For that he received $4.8 million he never reported to the IRS. If convicted, Pursley faces as much as 20 years in prison for tax fraud.

As in most tax cases, the evidence is complex and convoluted, but the contrasting perspectives – as presented in Tuesday’s opening arguments – are remarkably simple.

The government: Jack Stephen Pursley knew exactly what he was getting into when he agreed to help his business partner, Shaun Mooney, transfer $18 million in offshore funds and avoid paying federal income taxes in the process.

“This is a case about the responsibility to pay taxes, but it’s also a story about concealment,” Jack Morgan, a prosecutor for the government told jurors Tuesday morning. “In February 2007, Shaun Mooney had a problem. He had stashed millions of dollars offshore but didn’t want to pay taxes. The evidence will show that Mr. Pursley agreed to help.”

The defense: Pursley’s business partner did not tell him the whole truth about who really owned the companies the funds were in, thus Pursley was unknowing when he helped Mooney repatriate millions from overseas accounts.

Victor Vital, who represents Pursley, claimed before the jury that the only reason Pursley is standing trial is because his former business partner Shaun Mooney turned on him – falsely implicating him after a civil dispute between the two exposed his own tax evasion scheme.

Vital told jurors that they needed to look no further than an email that Mooney sent to his brother when their relationship soured asking for advice on getting rid of his Pursley as his business partner.

“Mooney tells the truth: ‘I created the business… and Mr. Pursley really knows nothing about this,’ ” Vital read to the jurors.

Vital says Mooney fooled not only Pursley, but other “very smart people,” including tax lawyers and a compliance officer for a financial service company in the Isle of Man that managed Southeastern Shipping’s accounts.

What Pursley didn’t know, said Vital, was the key fact in the case: that Mooney owned Southeastern Shipping, the oil rig recruitment company he was advising, not the person named on the company’s books: a Brazilian named Eduard Venerabile.

But in his opening argument Morgan, the federal prosecutor, maintained that Pursley had to know that Mooney, his business partner, was the real owner of Southeastern Shipping. Venerabile, a rig safety advisor and Mooney’s longtime friend, had no operational connection to the company and Pursley possessed a 2005 memo from the financial consultants KPMG stating as much.

What’s more, Morgan told jurors, prosecutors plan to show that Mooney and Pursley flew to the Middle East, where Venerabile was working, to provide a him script for a conversation that had been scheduled with a compliance officer who had raised questions about his ownership of Southeastern Shipping.

The case has garnered a great deal of attention within Houston legal circles. And three of the first four witnesses in the case were Houston lawyers who had been mentioned – but unnamed – in Pursley’s 2018 indictment. Each said they were approached by Pursley, each time with a different story.

Bill York was the first of the three. York said Pursley had presented himself as the “caretaker” of funds owned by a Brazilian who had “disappeared.” Pursley said he was trying to figure out what to do with the money.

After checking out Pursley’s story, York said he declined. “I didn’t believe it,” York told the jurors.

A second Houston lawyer, Tom Foster, testified that he provided Pursley with a legal opinion that reversed the earlier KPMG assessment: that Venerabile was, in fact, the beneficial owner of Southeastern. The information was based solely on information provided by Pursley, Foster said.

But the third Houston lawyer, Charles Michael Gillis, testifying under a non-prosecution agreement with the government, told the jury that he decided to work with Pursley, and began unwittingly to create companies to facilitate Mooney and Pursley’s scheme.

Gillis testified that he had proposed four different tax avoidance plans to Pursley and Mooney. The other three were rejected because they required some form of reporting to the IRS, Gillis said.

The plan they ended up using depended on the opinion provided by Foster, presenting Venerabile as the actual owner of Southeastern Shipping. The claim, Gillis said, was that Venerabile now wanted to transfer his entire interest in the recruiting firm to Mooney because Mooney had built the company and done all the work.

“It went against human nature,” Gillis said. But in two meetings with Venerabile, the Brazilian told him the same story.

“I thought I was dealing with honorable people who were telling me the truth,” Gillis told the court.

Gillis said that while working for the three men he considered clients – Mooney, Pursley and Venerabile – he interacted with Pursley “95 percent of the time.” Still, he said he first learned that Pursley was personally benefitting from the tax-avoidance maneuvers when he formed a company called Four Sevens Investments under Pursley’s name.

“I have no understanding…as to why he was getting that amount of money,” Gillis said.

The jury of ten men and four women, including two alternate jurors, was chosen after a voir dire conducted by Judge Hughes. His inquiries, given to a panel that remained remarkably silent, were based on written responses to questions from both sides; as a result, little was made known in open court about the jurors chosen.

Though prosecutors expressed no qualms about any specific juror, 10 were struck by the government. Pursley’s defense attorney, Victor Vital, cited concern about one, a man who had served as a government witness in a tax evasion trial before, which he said “struck a little too close to home.”

Judge Hughes pointed out that the man also appeared unhappy to be here, having noted multiple upcoming business and personal trips. He was one of 16 ultimately struck by the defense.

Testimony resumes Wednesday.

The Back Story

Prosecutors with the Department of Justice are accusing Pursley of helping a client transfer $18 million in offshore funds from the Isle of Man to shell companies in the U.S. by disguising the transfers as stock purchases. For his help in the elaborate scheme, the government says, Pursley received $4.8 million and received an interest in the client’s ongoing business – income never reported to the IRS.

The case has attracted attention among tax and white collar defense circles. Pursley faces three counts of tax evasion and one count of conspiracy to defraud the U.S. government, for which he could face up to 20 years in prison if the jury finds him guilty.

While the allegation of tax evasion is at the crux of the case, the story behind litigation features international intrigue, a relationship between business partners that soured and an underlying civil dispute that launched government scrutiny of their affairs.

According to court documents, the government’s star witness will be Shaun Mooney, Pursley’s former business partner. Mooney is listed as an interested party in the criminal case.

While details have been closely held by both sides, court documents suggest it was Mooney who provoked the federal investigation when he applied in 2013 for the Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program. The OVDP allows individuals who used offshore accounts to evade paying U.S. taxes to come into compliance, by reporting their transactions. Court records say Mooney signed an agreement with the IRS in June 2014, which resolved all criminal and civil liability for Mooney during tax years 2004 to 2011.

A federal grand jury in Houston indicted Pursley Sept. 20, 2018. The indictment also mentions three unidentified Houston lawyers (who have since been identified) as well as a Brazilian citizen as playing roles in the scheme — albeit some unknowingly, based on false information Pursley and Mooney allegedly provided them.

Pursley’s lawyers contend there is much more to the story.

“We have great respect for the legal process and are confident the truth will come out at trial,” said Vital and Nicole LeBoeuf, Pursley’s lead lawyers, told The Texas Lawbook in an email.

Prosecutors declined to comment on the case. The DOJ lawyers prosecuting the case for the government include Sean Beaty, Grace Albinson, Jack Morgan and Nanette Davis. All attorneys are based in Washington, D.C. and are part of the DOJ’s tax division.

The outcome of the verdict, according to legal experts, will hinge on two key questions: 1) how much did Pursley know, and 2) who between Mooney and Pursley will the jury believe?

“At the end of the day, this is a classic ‘he said, she said’ kind of case,” said white collar expert Bill Mateja, who is not involved in the litigation. “A lot will boil down to whether or not [Mooney] can withstand cross-examination by Pursley’s attorneys.”

“Pursley’s attorneys are going to need to demonstrate that if Mooney had told the truth about the facts that this strategy wouldn’t have been legitimate, and that Pursley had wool pulled over his eyes by Mooney,” Mateja added.

Mateja also emphasized that it will be crucial for the defense to demystify the world of offshore money and the notion that parking funds in a tax haven such as the Isle of Man doesn’t automatically mean one is breaking the law.

“Offshore tax strategies like we’re seeing here aren’t necessarily illegal,” said Mateja, who is currently representing Texas Attorney General Kan Paxton in his ongoing criminal securities fraud case. “I work with a number of individuals who have set up legitimate tax avoidance strategies, not to be confused with tax evasion.”

From Brazil, Isle of Man & Beyond

Pursley and Shaun Mooney – a Houston businessman identified as “Co-Conspirator 1” in the indictment – were friends from college at Texas Christian University. Court records show the $18 million in funds originated in Southeastern Shipping Company Limited, which until 2009 provided personnel services to clients who owned offshore oil rigs, primarily in the Middle East.

In 2009, court documents say, Southeastern Shipping essentially became a shelf corporation after its operations were transferred to Recruitment Partners, a Texas limited partnership in which Mooney and Pursley split a 74-26% ownership stake. Although Mooney retained continuous ownership of both companies, Mooney eventually began presenting Eduard Venerabile, a longtime friend and Brazilian citizen, as their nominal owner to conceal his true ownership.

The indictment alleges Pursley helped Mooney repatriate the funds between 2007 and 2013.

From the time Mooney formed Southeastern Shipping in 1999 to its dissolution, he retained the Isle of Man Financial Trust, a financial services firm on the U.K. island, to manage Southeastern Shipping’s accounts, according to court documents. Mooney instructed the firm in 2006 to form another company, Pelhambridge Limited, which the government alleges had “no legitimate business purpose” other than to facilitate the transfer of funds.

Court records indicate that employees of Isle of Man Financial Trust understood Pelhambridge to be a shelf company that invested in U.S. properties. Pelhambridge received its funds via loans from Southeastern Shipping. Court documents say that in some instances, Southeastern wrote off the loans due to Pelhambridge’s inability to repay.

The government alleges that Pursley demanded compensation from Mooney and thus received $4.8 million — or a 26% cut — of the funds he helped transfer. The government alleges the two transferred the first $2.735 million — of which Pursley received $900,000 — from Pelhambridge between 2007 and 2009 into a company Pursley formed called Diversified Land Holdings. Mooney then paid Pursley by way of a sham stock purchase by Diversified into Gulf States Management Corporation, which Pursley owned.

In 2009, after a compliance officer at Isle of Man Financial Trust expressed concerns about potential money-laundering, Mooney and Pursley consulted with several attorneys in Houston to transfer the remaining $15 million. But in doing so, the indictment says, they provided false or misleading information, while rejecting any proposals that would require them to declare the funds as income or pay U.S. taxes.

One Houston attorney, Charles Gillis, helped them form Australian Partners Holding Corp., an Australian investment company that became a vehicle for transfer of the remaining millions. The company was nominally owned by the Brazilian, Venerabile. The holding company then proceeded to make sham investments in three new companies — one owned by Pursley and two owned by Mooney. Pursley earned another $3.925 million out of the subsequent transfers.

Instead of reporting the funds as income, the government alleges, Pursley and Mooney reported their newly-earned wealth as “capital contributions” into the sham companies, and reported their withdrawal of the funds from the corporations’ bank accounts as non-taxable “loans” or “returns of capital” from the corporation.

The government alleges Pursley used his millions to buy properties in Houston as well as a vacation home in Vail, Colorado, which is currently on the market for nearly $2 million.

The trial is taking place in the U.S. District Court for the the Southern District of Texas. Although Judge Hughes has not assigned a set amount of hours per side to present its case, he has expressed to the lawyers that the trial should only last a week. The prosecution is projected to close its case sometime Thursday morning.

Pursley and the government are expected to show hundreds of documents to the jurors, including bank records, emails, memos, meeting notes and tax return forms.