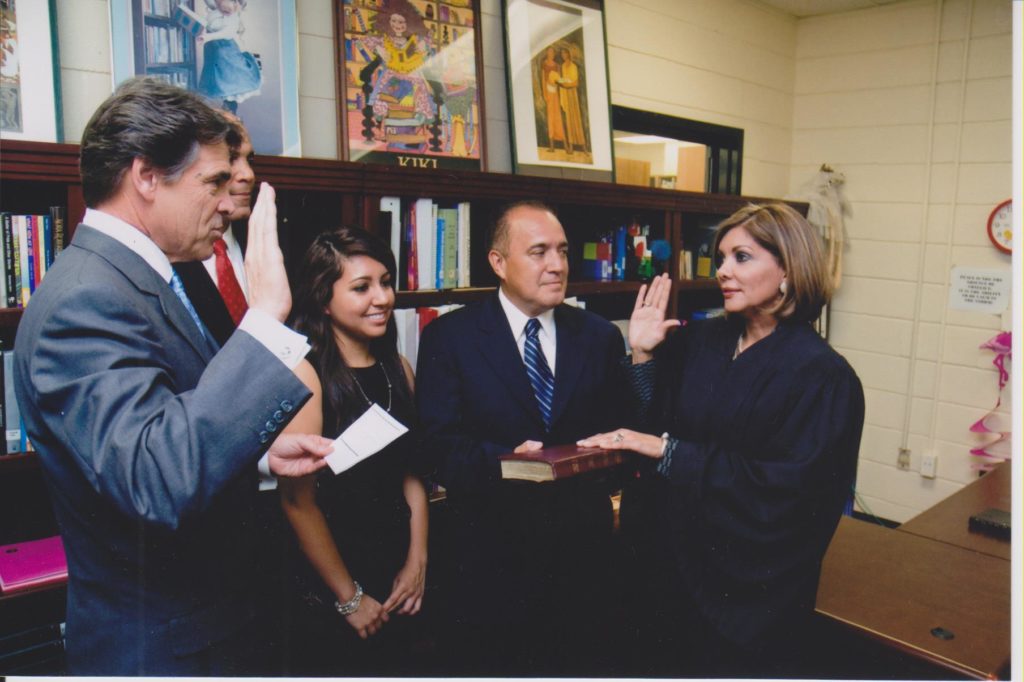

In 2009, Guzman was sworn in by Gov. Rick Perry at her former high school in Houston as her daughter and husband look on

Eva Guzman takes her place this fall as the senior justice on the Texas Supreme Court, capping a nontraditional path to the heights of the state judiciary and defying expectations of those who doubted that a female Hispanic Republican could make it in Texas politics.

Along the way to serving at the district court and two appellate court levels and becoming the first Latina elected statewide, Justice Guzman has proven that hard work, determination and empathy can make up for what some might consider obstacles to a career as an appellate jurist. She is the daughter of immigrant parents with limited education, her degree is from a regional law school, and her legal practice did not involve top tier law firms.

Guzman has served on the Supreme Court since being appointed in 2009 by then-Gov. Rick Perry to fill a vacancy. In 2010, she became the first Hispanic woman elected to statewide office in Texas. In 2016, she trounced opponents in the primary and general elections, burying the worry that Republican voters are unwelcoming to candidates with Hispanic surnames.

“I bring a sense of humility to my work,” Guzman recently told The Texas Lawbook. “I understand where there is room for growth and improvement and how to use resources to enhance my ability to serve the public.”

Her Supreme Court opinions have clarified the factors to be weighed when parties dispute the format for discovery of electronically stored information, narrowed the substantial-truth defense to defamation and determined who was entitled to $500 million in insurance coverage for subsurface pollution in the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

In June, Guzman wrote the majority opinion in a controversial decision that reversed disciplinary sanctions against a Dallas lawyer for allegedly attempting to taint a jury pool. Both trial and defense lawyers criticized the ruling and said it will make it more difficult for judges to police lawyer misconduct in cases before them.

“When bright-line rules are not possible, which is often the case, I strive to provide as much guidance as possible to help provide boundaries and contours to the law,” Guzman says.

Not one to be content with her considerable achievements, the conservative jurist in recent years has earned an LLM from Duke University School of Law, embraced her status as a role model for young Latinas and used her voice on the court to urge the Texas Legislature to improve school funding for economically disadvantaged students.

In September Guzman joined high court justices from three other states in a new podcast series, Lady Justice: Women of the Court. It is produced by the Arkansas Supreme Court to discuss the law and its real-world implications.

Albert Diaz, a judge on the U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals who has worked with Guzman on American Bar Association judicial education programs, says her work ethic can make 24 hours in a day seem like 48.

It’s fortunate, Diaz says, that Guzman is in a position to interact with judges, lawyers and the public.

“She’s always cognizant of trying to give back to others and helping others who are facing their own challenges to make their lives better, both personally and professionally.”

Family ties, ambitions

The nine-member Martinez family was close-knit and boisterous, given to robust debate around the dinner table. Guzman was born in Chicago where her parents settled after leaving Mexico in the 1950s looking for factory work and a better life.

“When I think about my parents going there without speaking the language with elementary school educations and navigating their way around the city, I admire them. I can’t imagine the courage that it took to make that journey,” she says.

When Eva was 6, the family moved to Houston where her father worked as a welder. She is the middle child among siblings that include a NASA engineer, a CPA and several successful business executives.

Guzman says her personal and judicial philosophies were forged during those dinner table discussions where different viewpoints were welcomed as long as they were voiced judiciously.

Guzman graduated from Stephen F. Austin High School, the oldest school in Houston’s East End. Her immediate dream was to become a flight attendant so she could travel for the first time.

She was instead steered toward college by her oldest brother, the NASA engineer, and enrolled at the University of Houston, where six of the Martinez siblings would obtain degrees.

Her studies sparked an interest in business, leading to a job in the brokerage division at a bank and obtaining a Series 7 securities license in her early 20s.

While still working at the bank to support herself, Eva began night classes at South Texas College of Law. She chose the school for its flexibility but benefited from its strong advocacy program.

‘You can’t go back there’

It was during law school that Eva met her husband, Tony Guzman, during a night out dancing with a classmate. The classmate left early and Eva found she was missing her keys at the end of the night. She approached a friendly police officer who said he didn’t have the keys but would call if they turned up.

“Anyway, it turns out they did have the keys but he just wanted my phone number,” she laughs. “He never stopped calling.”

After receiving her law degree in 1989, Guzman worked for a small law firm in the Galleria area doing a broad spectrum of legal work, including litigating partnership disputes and personal injury cases. She said the experience gave her a broader perspective about practicing law without the resources of a mega firm.

Guzman and her sisters with George W. Bush

“It prepared me well, I think, for my transition to the bench to have that type of hands-on experience,” Guzman says. “When I look at cases, I’m able to look at them through the lens of 90% of lawyers who don’t work at big firms.”

When her daughter Melanie was born, Guzman opened a solo practice with the soon-to-be mistaken hope that she would have more control over her time. She set up shop in an office-sharing arrangement and spent four years handling mostly family law cases.

Guzman’s preparation and courtroom skills were starting to get noticed, and she developed mentors through Houston Bar Association activities who encouraged her to apply for a vacancy on a family law bench in 1999.

During a mediation session, she asked for a break so she could drop her application in a FedEx box. Two days later, she was on her way to Austin for an interview with Gov. George W. Bush’s appointment staff. She soon got the call confirming she had beat out nearly 30 other applicants.

The first time Guzman walked into the 309th District Court and headed for the chamber, a bailiff told her she couldn’t go back there.

In her typically calm, respectful manner, Guzman replied: “Well let me introduce myself. I am Eva Guzman and I’m the new judge here.”

The bailiff apologized and Guzman got busy. She became known for her work ethic, fairness and experience gained from having litigated a number of cases.

Knowing what she didn’t like about some of the judges she had practiced in front of, Guzman says she “aspired to be the kind of judge that lawyers respected and thought they would get a fair shake from.”

As the first Latina to serve on a family court bench in Harris County, Guzman occasionally used her Spanish language skills to make sure court interpreters were properly communicating questions and answers. “At the time, it was unique to have that ability to communicate with litigants in their own language,” she says.

Impressing the governor

In 2001, Guzman gave a speech at a large Republican event about what it means to be a Latina Republican. As usual, she had worked hard on her three-minute speech, and Perry was among those who were impressed. He sent an aide to suggest she might want to serve in a different capacity.

“It was a bit of serendipity, frankly,” says Guzman. “A vacancy came open a few months after that. I became the first Latina on the appellate bench in Houston.”

Guzman served on the 14th Court of Appeals for almost a decade and says only one of the many opinions she authored was reversed. The intermediate appellate courts hear both civil and criminal cases, and Guzman initially sought guidance from a more experienced court colleague about the nuances of criminal law. She learned quickly and continued to be highly rated in local bar polls.

Brett Busby, who was appointed to the Supreme Court in 2019, considers Guzman a mentor from his days as a young appellate attorney in Houston. After watching her insightful presentation on appellate law at a Houston bar luncheon, he introduced himself.

“She was very gracious to give me some advice and help me get more involved in the appellate world there in Houston. She’s been a mentor of mine ever since,” Busby says.

Supreme campaigner

Guzman says she applied for vacancies on the Supreme Court a few times before Perry elevated her in 2009. She requested a ceremonial swearing in at her old high school, wanting students to witness the possibilities that come with education.

Fellow justice Nathan Hecht, now chief justice, says Guzman was fully prepared for the job.

“She has a very unusual, impressive background, and I think it’s given her the vision to kind of see the law and the justice system from a different perspective, which she has not lost by the way,” says Hecht.

In Texas, the high of a plum judicial appointment is often followed by the low reality of a partisan election where most voters don’t know the judicial candidates. Republican candidates have been safe in general elections for many years, but GOP primaries have at times proved hazardous to incumbents with Hispanic names.

“Early on, one of the challenges was, ‘Will the Republicans vote for a Latina?’ I knew that going in,” says Guzman. “My job was to explain to them what I brought to the bench and my judicial philosophy.”

With husband Tony receiving her LLM from Duke University

She recalls a small gathering in Navasota during her 2002 campaign for the court of appeals where she introduced herself to an older white voter, who grunted and took her brochure. Figuring that vote was lost, Guzman was surprised when the man came up to her after her speech, told her he believed she was the right person for the job and gave her a $15 check.

“I just treasured that,” says Guzman. “Here’s a gentleman, a farmer, who probably had never seen a woman of color come into his community and talk about serving as judge and making the system better.

“When campaigning, I think about him and that experience and how we can connect in ways that maybe we don’t even think about.”

In 2010 and 2016, Guzman beat opponents in the primary and general elections. She had the distinction in 2016 of being the top vote-getter of any statewide candidate in both the primary and general elections.

Guzman began using Twitter to communicate about her campaign and has since evolved to commenting on civic issues. Her 7,300 followers get an intriguing mix of information about the judiciary, messages of faith and social justice, and mouth-watering images of her Mexican cooking.

In recent months, Guzman has tweeted about the importance of wearing masks and the need to intentionally focus on racial justice in child welfare cases. She prompted a discussion thread about what women of color do to make their white co-workers feel comfortable.

On June 4, Guzman tweeted about a state senator who told her “we had our doubts” when she was appointed to the Supreme Court but that she had “ended up doing great.”

The tweet continued: “Me in my head: WTH. Me to Senator: ‘glad I exceeded your expectations.’ He thought he paid me a compliment. Happens all the time.”

Guzman says social media is a vehicle to highlight issues that merit attention from the public and decision-makers.

“You can’t ignore away the issues of bias, that these things are happening,” she says. “We should look at ways to not only change the system ourselves but to inspire other people to pursue change.”

In the wake of violence involving communities of color and law enforcement and the killings of five Dallas police officers in 2016, Hecht tapped Guzman to lead a summit to address unconscious bias sponsored by the Supreme Court and Court of Criminal Appeals. The summit produced an online curriculum that communities can use to critically examine themselves.

Consenting for change

Guzman was a member of the 2011 inaugural master’s in judicial studies class at Duke’s law school. She studied dissenting opinions and surveyed 150 judges from 49 state courts of last resort about what factors influenced their decisions to dissent and what it cost in collegiality and extra work.

A rare dissenter on the conservative, cohesive Texas Supreme Court, Guzman has regularly used concurring opinions to speak to the Legislature about needed statutory changes.

Her most high profile concurring opinion came in the 2016 case that upheld the constitutionality of the beleaguered school finance system. Guzman, joined by Justice Debra Lehrmann, wrote of the need for the Legislature to support the 60% of students who are economically disadvantaged. She said that Texas “should aspire to more than being solidly in the middle” of national academic rankings.

To the surprise of many, the 86th Legislature in 2019 for the first time revised school finance laws in the absence of an order from the Supreme Court. Lawmakers pumped $6.5 billion into school funding, including money targeted at economically disadvantaged students.

Guzman also has used concurrences to encourage the Legislature to review laws that preempt cities from passing plastic bag bans, consider waiving immunity for prosecutors who withhold exculpatory evidence and allow parents of deceased workers to recovery exemplary damages for intentional workplace injuries.

“I have a judicial philosophy that respects the separation of powers, and our role as jurists is not to create laws and not to extend them in ways that invade the province of the Legislature. Sometimes I write to speak to the Legislature about changes that would produce a better outcome for Texans,” she says.

Second-generation lawyer

Last year, Guzman administered the new lawyer oath to her daughter. The occasion prompted reflection on the profound differences in their respective journeys to the law.

Thirty years ago, Guzman was entering an unfamiliar world she had studied but not seen firsthand. Melanie, who graduated from Harvard University and Duke Law School, had seen the practice of law from all sides.

“Knowing that Melanie chose a life in the law truly understanding the dedication and responsibility the profession demands made welcoming another committed Latina to the bar particularly rewarding,” says Guzman.