© 2013 The Texas Lawbook.

By Mark Curriden, JD

Senior Writer for The Texas Lawbook

(Editor’s Note: A variation of this article is in the February issue of the ABA Journal, which we invite you to read.)

NEW ORLEANS (February 2) – In 1953, Richard and Corine Stewart took their two sons to look at the new property where the couple planned to build their first home.

The housing development was in a section of Shreveport that was experiencing economic growth. Richard, a postal carrier, and Corine, a domestic worker, could hardly contain their excitement about owning their first home.

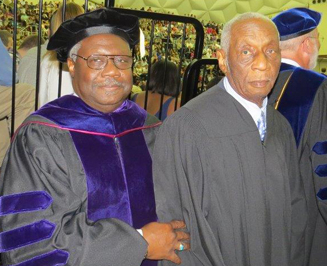

Centenary College in 2013.

“We were so excited about our new home,” says Richard Stewart Jr., who was seven at the time. “Then, all of sudden, it didn’t happen.”

Down the street, leaders of the all-white Emmanuel Baptist Church were watching. Church members didn’t want black families moving into their neighborhood and sought to have building permits reversed. They convinced local leaders to deny water services and police and fire protection to the new housing development, which led insurance companies to raise doubt about offering coverage to the new home.

As a result, the property the Stewarts bought was essentially worthless. The house was not built.

“It devastated our parents,” Richard Stewart Jr. says. “Our parents tried to shelter Carl and me, but we knew. We could see the pain and disappointment and frustration in their faces.”

Carl was only three. Over the next couple decades, he would face constant and repeated discrimination. He attended segregated schools, used “coloreds only’” restrooms and water fountains and sat at the back of the bus.

Retail stores refused to let him try on clothes to see if they fit. Customers at his first job in college routinely used the “n” word to him. He quietly admits that he continues to experience racial profiling even today.

Any of these would make most people angry for life.

Not Carl Stewart.

In fact, Stewart, who is now 63, is by all accounts one of the most kindhearted, gentle, easygoing and fair-minded people walking the face of the planet.

In fact, Stewart, who is now 63, is by all accounts one of the most kindhearted, gentle, easygoing and fair-minded people walking the face of the planet.

“I don’t see why so many people, even today, are so bitter or always picking fights over politics or race or whatever and I refuse to play their game,” says Stewart. “I believe in basic life principles: be nice to others; be fair to everyone; and help those who need help.

“People who constantly cause conflict and stress, those are unhappy people,” he says.

Stewart is the chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. He serves on the powerful Federal Judicial Conference, is vice president of the prestigious American Inns of Court and, until recently, chaired the Federal Rules Committee.

There is no disputing that Stewart is one of the most influential federal judges in the entire nation.

There is no disputing that Stewart is one of the most influential federal judges in the entire nation.

During the past several months, Chief Judge Stewart granted me multiple lengthy interviews for an ABA Journal article, which was published last week in its February issue. The article covers multiple lengthy interviews about his childhood, law school years, career as a lawyer and judge, his time on the Fifth Circuit, his judicial philosophy and his management style as head of one of the more controversial, rancorous, staunchly conservative and important appellate courts in the country.

As the Fifth Circuit’s first African-American chief judge, he knows he is under the spotlight and is definitely enduring his fair share of stress.

© 2014 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.