© 2012 The Texas Lawbook.

By Mark Curriden, JD

Senior Writer for The Texas Lawbook

FORT WORTH (July 11, 2012) – Very few corporate executives or general counsels have ever heard of Michael King.

An assistant director of enforcement with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s Fort Worth Regional Office, King is the lead lawyer in two of the biggest corporate financial investigations the federal government is conducting.

King, who is 38, will not discuss either inquiry – one into whether senior Wal-Mart executives bribed Mexican officials in an effort to gain advantages over their competition and the other into allegations that top corporate leaders at Chesapeake Energy committed fraud and misled investors. In fact, King cannot acknowledge that these investigations even exist.

“Michael is calling the shots,” says a lawyer with knowledge of the two inquiries. “He’s intimately involved.”

The two cases, according to lawyers familiar with the investigations, are likely to thrust King into the global spotlight. Both matters have the potential to become historic prosecutions as the companies face hundreds of millions of dollars in civil fines and as much or even more than that in disgorgement of profits. Executives at Wal-Mart could even face jail time.

But the cases also offer an extraordinary opportunity for the SEC’s much maligned Fort Worth Regional Office to finally achieve public redemption after years of criticism by Congress and the SEC’s own inspector general for its handling of the Stanford Investments scandal.

“The pressure on Michael and the Fort Worth office right now is enormous,” says Kit Addleman, a partner at Haynes and Boone who specializes in securities litigation and white-collar criminal investigations. “The entire office is very anxious to get out from under the negative reputation.”

“For years, New York or Washington, D.C. would beat Fort Worth to the punch in grabbing the big cases,” says Addleman, who worked with King at the SEC until 2009. “Not this time.”

By assigning King to lead the Wal-Mart and Chesapeake investigations, SEC senior leaders are signaling that they entrust two of their biggest and highest profile cases to the Fort Worth office, according to securities law experts.

“I view the spotlight as an opportunity,” says King, a 2001 graduate of the SMU Dedman Law School. “If you want to do important work – work that people care about and that makes a difference, the spotlight automatically comes with it.”

The Wal-Mart case demonstrates a noticeable shift for the Fort Worth office, which has been criticized for years for focusing on smaller, easy-to-win cases and shying away from more resource-intensive, higher risk investigations, according to securities law insiders.

David Woodcock, who is approaching his one-year anniversary as the director of the SEC’s Fort Worth Regional Office, admits that King and the Fort Worth office are under the microscope – internally by superiors at the SEC in Washington, DC and externally by Congressional leaders and SEC watchdogs.

“The expectations of Michael and this office are very high and a lot of pressure comes from those expectations,” says Woodcock. “The leadership in DC expects big things from this office.

“Michael is aggressive, smart, hardworking and hungry,” says Woodcock, who like King, declines to comment on the Wal-Mart or Chesapeake investigations. “He holds himself and others to a very high standard.”

No current SEC inquiry has a higher profile than the one focusing on Wal-Mart, which burst into public view in April with a front page article in the Sunday New York Times.

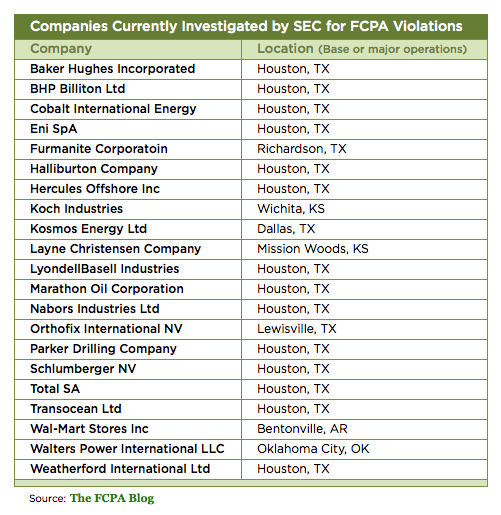

The investigation, which is being jointly conducted with the U.S. Department of Justice, examines allegations that executives in the Arkansas-based retailer’s Mexican operations paid $24 million over several years to local government officials in Mexico in order to receive licenses and permits to open stores faster and in more ideal locations, which would be a violation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

King and his team also are probing allegations that senior Wal-Mart executives in the U.S. knew about the bribes and did nothing to stop them and may have acted to cover them up.

“The conduct of Wal-Mart, if it has been accurately reported, was horrific,” says Jeff Ansley, a former SEC enforcement lawyer and now a securities litigation partner at Curran Tomko Tarski in Dallas. “This conduct appears to have been pervasive and extended to the highest ranks at Wal-Mart.

“I think King is under tremendous pressure to make Wal-Mart the poster child for what happens when corporations violate Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and then don’t self-report,” says Ansley. “The great thing about King is that he will not hesitate to make Wal-Mart that poster child if he thinks the evidence warrants it, but he also has the integrity to say when an investigation has gone far enough.

“Either way, this is also a great opportunity for the Fort Worth Regional Office to showcase its expertise for all to see,” he says.

Ansley and other legal analysts say that King’s investigation into Wal-Mart is not limited to the company’s conduct in Mexico. They say the inquiry is exploring the possibility that the retailer’s conduct is systemic and reaches into other areas of the company’s global operation.

The SEC’s probe into Chesapeake examines whether Aubrey McClendon, the Oklahoma City-based oil and gas company’s CEO and co-founder, improperly borrowed $1.5 billion from investment firms doing business with Chesapeake and whether he failed to properly inform his board of directors and investors of his actions. But other SEC watchers believe that regulators are also interested in Chesapeake’s balance sheet and whether company officially have been completely transparent about the amount of debt the it has been accumulating.

Both the Wal-Mart and Chesapeake cases could mean significant amounts of billable hours for Texas lawyers.

Wal-Mart has hired Rob Walters, a litigation partner at Gibson Dunn & Crutcher and former Energy Future Holdings General Counsel, to defend it against shareholder lawsuits filed as a result of the alleged corruption.

Jones Day is handling Wal-Mart’s internal investigation. Sources say that Dallas securities litigation partners Wes Loegering and Joshua Roseman are playing key roles for Jones Day.

Meanwhile, Chesapeake has retained Bracewell & Giuliani white-collar defense attorney Patrick Craine, a partner in the firm’s Dallas office, to represent the company. Craine is a former enforcement lawyer who worked with King in the SEC’s Fort Worth office.

But the eyes of the lawyers working for the targeted corporations are most certainly fixated on Michael King.

“I promise you that lawyers for Wal-Mart and Chesapeake are researching Michael and the various cases he’s handled to see if it gives them any insight into how he will move forward in these cases,” says Ansley.

King grew up in Franklin, Tenn. His dad was a small town lawyer whose office was connected to the family home, which was only a block from the town square and the courthouse.

“My dad hung out a shingle on the front of our house that said he accepted all comers as clients,” says King. “My dad is my hero as a lawyer. He always put his client’s ahead of his own interests, even when they couldn’t pay.”

By high school, King realized he had a wicked swing and a pretty good putting game, too. He received a scholarship to play golf at Vanderbilt University, where he later became captain, and he had visions of being a pro-golfer.

“Michael is no shrinking violet – on the golf course or at work,” says Jacob Smith, a former law school classmate at SMU and friend of more than a dozen years who is now the general counsel at Luther King Capital Management in Fort Worth. “In fact, he relishes the pressure. The pressure makes him work harder.”

Once King realized that the professional golf tour was not in his future, he enrolled at in law school at SMU. But classmates quickly realized there was more to King than just golf and getting a job.

“Mike was the one we all knew would go into public service,” says Michelle Hartmann, a securities litigation partner at Weil, Gotshal & Manges and a former classmate of King. “You could see his ambition. Everything Mike did, he threw himself into.”

King says he initially planned to return to Tennessee to possibly practice law with his father or at a law firm in Nashville.

“I decided to stay in Dallas to leverage the SMU Law School name and the contacts I made while I was there,” he says.

Upon graduation, King joined Haynes and Boone’s Dallas office for the opportunity to work with prominent trial lawyer George Bramblett, which he did for two years. He says it was a great learning experience.

In 2003, a friend at the SEC recruited King to join the regulatory agency as a staff attorney. It was a hot time to be a securities prosecutor, as Elliott Spitzer was making headlines going after investment banks and hedge funds.

“It was amazing,” says King. “I went from sitting second or third chair in a case where I had no decision-making authority or influence to leading cases on the front page of the newspaper.

“The work we do is sophisticated and important,” he says. “Our cases can have major public policy implications and they impact a lot of people.”

Steve Korotash, the former head of the SEC’s enforcement division in Fort Worth and now a partner at K&L Gates in Dallas, promoted King twice during the past decade.

“Michael is a super lawyer in an office of truly excellent lawyers,” says Korotash. “He is dedicated to the mission of the SEC. He has the ability to see the forest over the trees and how to get to the meat of a case.”

Legal experts say that Wal-Mart and Chesapeake lawyers are likely studying two specific cases handled by King that might provide insight into how he will lead their inquiries.

Wal-Mart lawyers are surely examining King’s civil prosecution of global freight forwarding corporation Panalpina, Inc. and six oil services companies, which the SEC accused of violating the FCPA in 2010.

King and his team learned that the companies were bribing officials in 10 countries in an attempt to circumvent rules and regulations, giving those businesses operating advantages in those nations. King prosecuted two of the companies, Panalpina and Pride International, while other SEC regional offices handled the other five businesses.

In a settlement reached with the SEC, which was filed in the U.S. District Court in the Western District of Texas, Panalpina admitted to paying $27 million in bribes to foreign officials. The bribes were falsely recorded as legitimate business expenses in the company’s financial statements. And the companies did not self-report the FCPA violations.

The seven corporations agreed to pay $156.5 million in fines and $80 million in disgorgements.

The facts in the Panalpina case, according to lawyers following the Wal-Mart investigation, parallel the allegations that have surfaced against the retailer, with one major exception: Wal-Mart’s revenues from its Mexico operations were multiple times more than those of the seven companies in the 10 countries.

Lawyers familiar with the Wal-Mart inquiry say that could mean that the fines and disgorgements would be multiple times more – possibly exceeding $1 billion.

“The SEC and Justice Department have made it clear that self-reporting is critical in how it approaches FCPA investigations,” says King. “In most cases, FCPA inquiries are largely dependant on a corporation’s internal investigation and on the cooperation of that corporation’s legal counsel with the SEC staff.

“In resolving FCPA cases, the SEC looks for opportunities to give credit to those corporations that self-report and cooperation, which incentivizes others companies to do the same,” he says.

Hartmann, who has represented companies that were the target of King’s investigations, advises lawyers for Wal-Mart and Chesapeake against trying to bully King.

“Pounding the table,” she says, will not work.

“Our case got contentious at points, but Mike was always open to hearing our client’s side,” says Hartmann. “Mike is the future of that office and SEC leadership is right to have him take on these very important cases.”

King is not new to controversy. In 2007, he was promoted to the position of branch chief. Among the new case files that came with the new job: allegations of fraud against Houston investor Allen Stanford.

A file on Stanford had been opened years before King had been hired. It had been passed around the SEC’s Fort Worth office from lawyer to lawyer, but the case never became a priority, according to lawyers with knowledge of inquiry.

Upon taking his new leadership role, King reviewed the case file and made a decision in April 2008 to refer the matter to the Justice Department.

“There was a real concern about jurisdiction regarding off-shore banks,” says King. “Referring the case to the DOJ was one of the best decisions I have ever made. At that point in time, DOJ was much better positioned to move forward with the case.”

Others say that King’s superiors simply didn’t want to take the risk of using significant resources on an investigation that might not yield a prosecution.

By late 2008, the financial crisis had struck and the DOJ was still investigating and had not moved to shut down Stanford. Meanwhile, the SEC was receiving more complaints and more insider information.

King and his superiors called the Justice Department saying they wanted the case back.

“Four of us lived in a conference room on the 11th floor, 15 hours a day seven days a week for 12 weeks, going through every piece of paper we had on the case,” says King. “At 12:30 a.m. on February 17, 2009, we made the decision and as soon as the courthouse opened the next morning, we filed.

“We understand that the great work done at the end by the team that inherited the Stanford investigation is no consolation to any of those who lost their life savings,” he says. “There’s no one at the SEC who doesn’t wish things had worked out differently… better.

“The 90 days that our team spent in that conference room informs my belief that the lawyers in our office are more than capable of prosecuting the SEC’s highest priority cases.”

© 2012 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.