© 2012 The Texas Lawbook.

– all photos courtesy of The Dallas Morning News

By Mark Curriden

Senior Writer for The Texas Lawbook

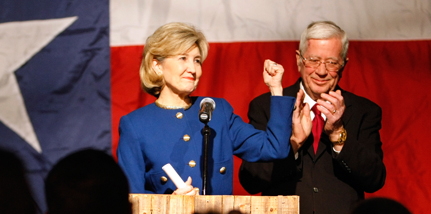

Business leaders, government officials and supporters lined up to greet U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison. They gave her business cards, brochures, documents and various promotional trinkets, which she turned and handed to an older white-haired gentleman quietly and patiently standing in the background holding her bag.

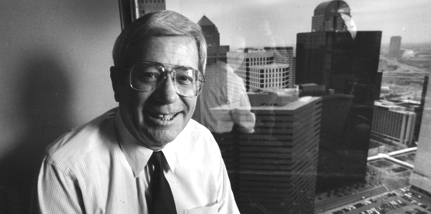

Meet the individual who has had arguably the single biggest impact on the North Texas economy for the past half-century.

No, not Senator Hutchison. The white-haired man in the back.

His name is Ray Hutchison, the senator’s husband. He’s also a municipal bond lawyer who was intricately involved in the creation, development and construction of the most important economic drivers in the Dallas-Fort Worth region.

Intricately involved, officials say, means that DFW Airport, DART, the Upper Trinity Regional Water District, the AT&T Performing Arts Center and every major professional sports facility that has been built during the past 45 years are a reality because of Ray Hutchison.

Hutchison led the negotiations to move the Washington Senators to Arlington to become the Texas Rangers and then handled the highly complex legal work required to build the team a new stadium. He represents the Dallas, Highland Park, Irving and Richardson school districts in all their expansion efforts.

He handled Parkland Hospital’s recent $700 million bond issuance and, just last month, Baylor University hired Hutchison to handle about $200 million in public financing on its new football stadium, which is set to open in 2014.

“Ray has been involved in virtually every major government development project of the five decades,” says Ben Brooks, Hutchison’s long-time friend and law partner at Bracewell & Giuliani. “Ray has easily been involved in more than $20 billion in bond issuances that have directly and positively impacted the North Texas economy.”

Former Dallas Mayor Ron Kirk once joked that DFW Airport should be renamed the “Ray Hutchison International Airport,” because without him, it would not exist.

“There’s no question that Ray has played an integral role in the economic development of the Dallas-Fort Worth area,” says Kirk, who is now the U.S. Trade Ambassador. “Certainly no lawyer has had a bigger impact.”

Two weeks ago, Hutchison turned 80. The only celebration was with family and a few friends. One close colleague said, “Ray wanted it that way” because he doesn’t want to detract from the attention Sen. Hutchison is getting as she wind downs her service in the U.S. Senate.

“Ray is truly one of the great lawyers ever in Texas – he’s an architect who takes the dreams of our local leaders and makes it come true,” says Judge Patrick Higginbotham of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and a good friend of the Hutchisons.

“But it is a testament to Ray’s character that he has taken a purely supportive role with Kay when Ray himself could have been senator or governor,” says Judge Higginbotham, who gives Ray Hutchison tremendous credit for his appointment to the federal bench. “Kay is very lucky to have Ray by her side.”

Hutchison didn’t grow up thinking he wanted to be a lawyer. “No one grows up dreaming of being a bond lawyer,” he says.

Hutchison grew up in Dallas, graduating from Crozier Tech on Bryan Street downtown because his family wanted him to be an auto mechanic. Classmates included Fritz “The Claw” Von Erich, the professional wrestler.

“Fritz and I were two of the few in my class who didn’t end up in prison,” he says. “I don’t think either of us made particularly good grades.”

A year later, in 1951, he was working as a messenger for Magnolia Oil Company when he received a letter from the U.S. Navy: “Congratulations, you’ve been activated. Report in two weeks.”

“College was nowhere in my thoughts at the time,” he says.

That changed once he was released from the Navy because he knew he could use the GI Bill.

“I asked SMU if I could get an extra scholarship, but the admissions fellow looks at my grades and laughed and said, ‘Are you kidding me?”

Hutchison had the last laugh. After graduating as a business major, he received his juris doctor from SMU Dedman Law School, graduating fourth in his class.

Initially, Hutchison worked as a litigator at the law firm that later became known as Jenkens & Gilchrest, where he was helping represent the Murchison brothers in their legal battle to buy New York-based investment holding company Allegheny Corporation. The legal battle required Hutchison to basically live in New York for a year on the case, which at the time was the largest hostile takeover bid in the U.S.

After a little more than a year, he decided he wanted a change of pace. He joined McCall, Parkhurst & Horton, which is one of the oldest and most prestigious municipal finance practices in Texas.

Hutchison was handling basic school bond issuances and had just helped create the Tarrant County Junior College in 1965 when he was asked to meet with government leaders in Dallas, including then-Mayor J. Erik Johnson and George Underwood, about building a new international airport.

There were numerous obstacles from the start, according to Hutchison.

“The airlines, led by Braniff, American and Delta, were absolutely opposed,” he says. “And the city attorneys of Dallas and Fort Worth wouldn’t even speak to each other.”

Hutchison recommended the creation of a multijurisdictional airport authority. He drafted a state constitutional amendment and enlisted the support of then-Governor John Connally, who helped get it passed in the Texas Legislature. But the required referendum failed in Dallas County.

The airport project was all but dead when Hutchison came up with an alternative. He unearthed an obscure Texas law passed in 1959 to allow the creation of a temporary multi-jurisdictional agency, which was needed by Odessa officials to build their airport. The one condition was that none of the airport could be financed with taxpayer dollars.

Hutchison got the approval of Dallas City officials and he physically tracked down the mayor of Fort Worth, who was literally on a gurney headed into kidney surgery.

“I’m not going to sign it because I don’t trust Dallas,” the mayor told Hutchison. But the bond lawyer was able to convince the mayor that it was a good deal and that no tax money would be used.

Hutchison did the legal work to issue and sell $35 million in bonds to North Texas Bank for the purchase of the land and construction of the airport, which then forced the airlines to the negotiating table. Since then, Hutchison has represented DFW Airport in each of its expansions, which have used more than $4.6 billion in bond issuances.

“The DFW Airport board was created as a temporary board and 46 years later, no one has ever challenged the board’s authority,” he says. “The people on the DFW board and all the local government leaders today would probably be shocked to know that it is still operating as a temporary board to this day.”

In 1967, Clint Murchison Jr. called Hutchison saying he wanted to build a new stadium for the Cowboys. Hutchison joined Murchison at a meeting with Dallas leaders, but it was clear they weren’t interested in building a new football stadium.

But Murchison gained the interest of Irving officials, who immediately hired Hutchison to negotiate for the city.

“The challenge was that Irving had no money, so we needed to get creative,” he says.

Within weeks, Hutchison presented a proposal: sell seat option bonds, which are now more commonly referred to as seat licenses. At the time, only a couple much smaller facilities had tried it.

“It turned out to be a major success,” he says. “Some of the seat option bonds for suites initially sold for $50,000 but later sold for $1 million. Texas Stadium ended up costing $35 million, but not a single dime of taxpayer money was involved.”

Then-Irving City Attorney John Boyle says Hutchison is “the most innovative public finance lawyer to ever practice law.”

“Ray drafted a plan of financing from scratch, which is highly unusual because bond lawyers almost always rely on what’s been done in the past,” says Boyle. “The City of Irving followed Ray’s plan and it worked exactly as he predicted.”

Not that there were obstacles to overcome. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission had passed a rule that would take effect January 1, 1968, which would have prohibited Irving from using the seat option bond plan.

Hutchison and Boyle immediately flew to Washington, DC, for a meeting with the SEC’s general counsel.

“For one-hour, Ray laid out his position for the general counsel on why this brand new SEC rule didn’t apply to Texas Stadium,” says Boyle. “It was some of the best lawyering I’ve ever seen.”

When Hutchison finished, according to Boyle, the SEC’s general counsel leaned forward and said, “We’ve worked on this rule for 10 years, but in 10 days you’ve found a hole large enough to drive a truck through it.”

The SEC gave Irving its waiver and Texas Stadium became the first large sports complex to be built using the seat licenses.

In 1971, Arlington Mayor Tom Vandergriff wanted to bring major league baseball to the Dallas suburb. He hired Hutchison to negotiate with Major League Baseball about relocating the Washington Senators.

“I recommended that Arlington buy the broadcast rights for the Washington Senators for 10 years to help bail out the financially struggling team,” says Hutchison.

The negotiations were held at a hotel in Boston. MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn adamantly opposed the Senators’ move. Hutchison quickly learned that someone else much more powerful also was against Arlington.

“In the middle of negotiations, there was a knock on the conference door,” he says. “A porter wearing white gloves walked in with an envelope on a silver plate.”

The letter was addressed to the owners of the American League clubs.

“I implore you. Repeat, I implore you. Do not move the national pastime from the nation’s capital.”

It was signed, “Richard M. Nixon, President of the United States.”

“Everyone was silent except Commissioner Kuhn, who was sitting next to me,” says Hutchison. “ He turned and punched me in the ribs and said, ‘Gotcha now, you son-of-a-bitches.’

“An hour later, we closed the deal and the Washington Senators became the Texas Rangers,” he says.

In the years that followed, Hutchison played crucial roles in the creation and public financing of Reunion Arena and then American Airlines Center, the Ballpark in Arlington, Cowboys Stadium, Texas Motor Speedway, and Gerald Ford Stadium at Southern Methodist.

“Ray knows more about how to do these kinds of projects than the rest of us put together,” says Dallas Cowboys General Counsel Alec Scheiner. “Ray is a businessman and a lawyer for his client. As a result, we didn’t fight over small details when we negotiated the new Cowboys Stadium deal.

“I’m just sorry that the City of Arlington hired him before we were able to,” he says.

Hutchison says he knew he had an advantage because the Cowboys’ lease at Texas Stadium would expire in less than two days.

“I sat down over a weekend and I created a ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ list,” he says. “The Cowboys took it.”

In the mid-1970s, Hutchison tried his hand at politics, running and winning two terms in the Texas Legislature. The big issues in his 1972 campaign were abortion, school financing and the Equal Rights Amendment.

During his four years in the state house, he met a fellow representative from Houston named Kay Bailey, who had introduced legislation in 1973 to create a regional transit authority in Houston, which would be funded by a one-cent sales tax.

The City of Dallas initially opposed the legislation. So, Hutchison rewrote it to Dallas’ satisfaction. A decade later, Hutchison used that exact legislation to help create the Dallas Area Rapid Transit system. He has been DART’s bond counsel ever since, handling more than $3.2 billion in bond issuances.

“Ray writes the legislation, works to get the legislation passed and then implements the legislation, which sometimes means creating the client,” says Brooks. “Then, he represents the client in public financing matters.”

In 1978, Hutchison ran for the Republican nomination for governor, but lost to Bill Clements. Following the political loss, he refocused on his bond practice and only reappeared in political circles periodically.

Hutchison found his work under attack in 2009 when Sen. Hutchison ran for governor against Rick Perry. The governor’s campaign accused him of using his wife’s position to attract clients – a claim that even many Perry supporters denounced as untrue and outrageous.

“Ray was a great bond lawyer well before Kay became a U.S. Senator and the accusations of conflicts of interests against him were just silly,” says Darrell Jordan, a long-time Dallas lawyer and prominent Republican. “The truth is that Ray got a lot of work despite his politics because he’s been the best bond lawyer in town for a long time.”

At age 80, Hutchison still goes to the office every day. He still loves the challenge of solving problems for his clients. And he has no plans to retire.

“Ray is the legal architect of a fair piece of North Texas,” says SMU Dedman Law School Dean John Attanasio. “He’s done so much great work for SMU, but his work creating and building DFW Airport into a world class transportation hub may be the single biggest factor in the economic development of our region.”

Back in his office at Bracewell, Hutchison pauses, as if mentally reviewing all the deals he’s led.

“I was there for the groundbreaking at Texas Stadium and I was there for the demolition,” he says. “I’ve helped build stadiums for every sports team in Dallas twice. I’m not sure I will be around in 20 or 30 years when the Mavericks, Cowboys and Rangers go for the third round.”

© 2012 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.