A state senate committee, voting along party lines, approved two bills Thursday that would radically change the appellate landscape across the state and that have already raised questions of partisanship and voter dilution, particularly that of Hispanics.

One bill (SB 11) would reduce the number of courts of appeals from 14 to 7, significantly realigning the existing boundaries of the current courts of appeals. The other (SB 1529) would create a new statewide Texas Court of Appeals that would hold exclusive jurisdiction over lawsuits involving Texas agencies and constitutional issues.

Before the votes by the Senate Committee on Jurisprudence, both bills were confronted with significant criticism in public hearings, but in each case the committee voted 3-2 to send the bills to the Texas Senate for a vote.

The chair of the committee, Sen. Joan Huffman (R-Houston), sponsored both bills. She described them to the committee as efforts to make the appeals courts more efficient by balancing dockets, reducing the number of inter-court transfers and eliminating conflicts between the various courts of appeals.

But over the next three hours witness after witness spent two minutes each criticizing, for the most part, the potential effects of the legislation and what they perceived as a lack of transparency evident in the process. Of particular concern to most was a realignment of counties that could result in a reduction of minorities on the appellate bench.

“This is restructuring, not redistricting,” asserted Huffman, who pointed out that there had been no large scale restructuring of the Texas court system in 40 years.

“It has the effect of redistricting,” said Sen. Juan Hinojosa (D-McAllen), the committee’s vice chair. “And it seems to me it’s a violation of the Voting Rights Act.”

“It would reduce the ability of minorities to elect the judges of their choice,” Hinojosa said.

Sen. Nathan Johnson (D-Dallas), who sits on the committee, concurred with Hinojosa. He said the two proposals seemed like radical solutions to problems that could be solved in simpler ways.

“It just seems to me a consolidation of power with partisan intent,” said Johnson.

“It feels like that we take a legitimate question, then use it to pursue illegitimate ends through illegitimate means.”

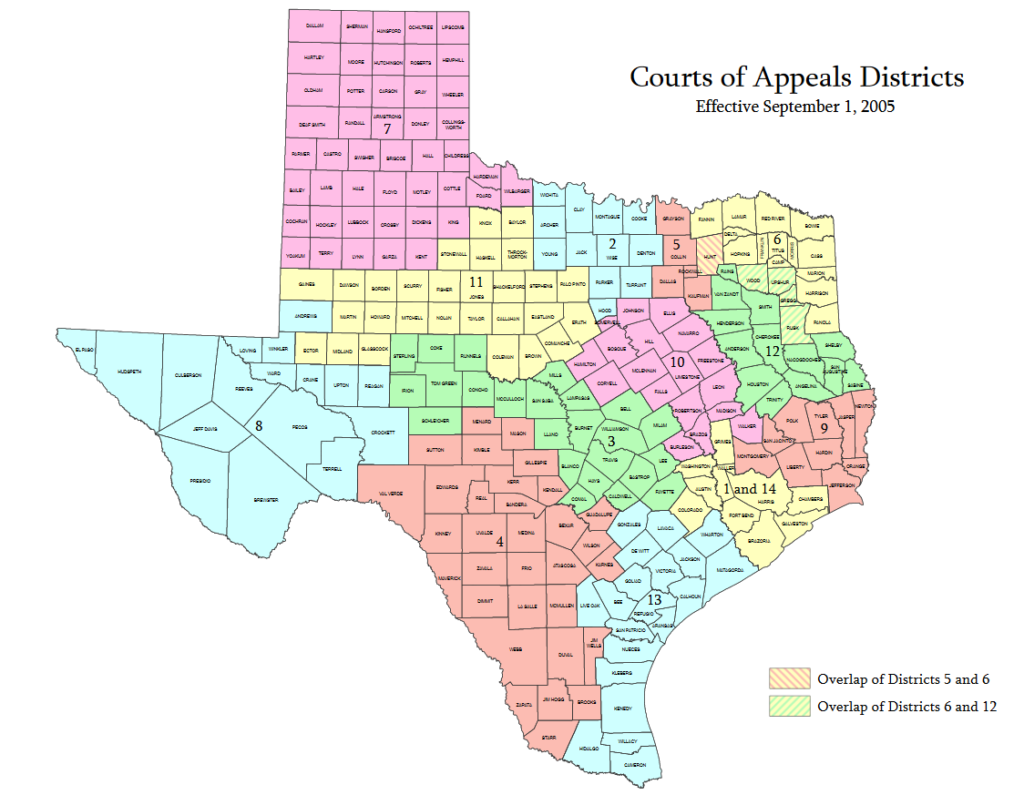

In essence, the bill seeks to realign the current districts from this:

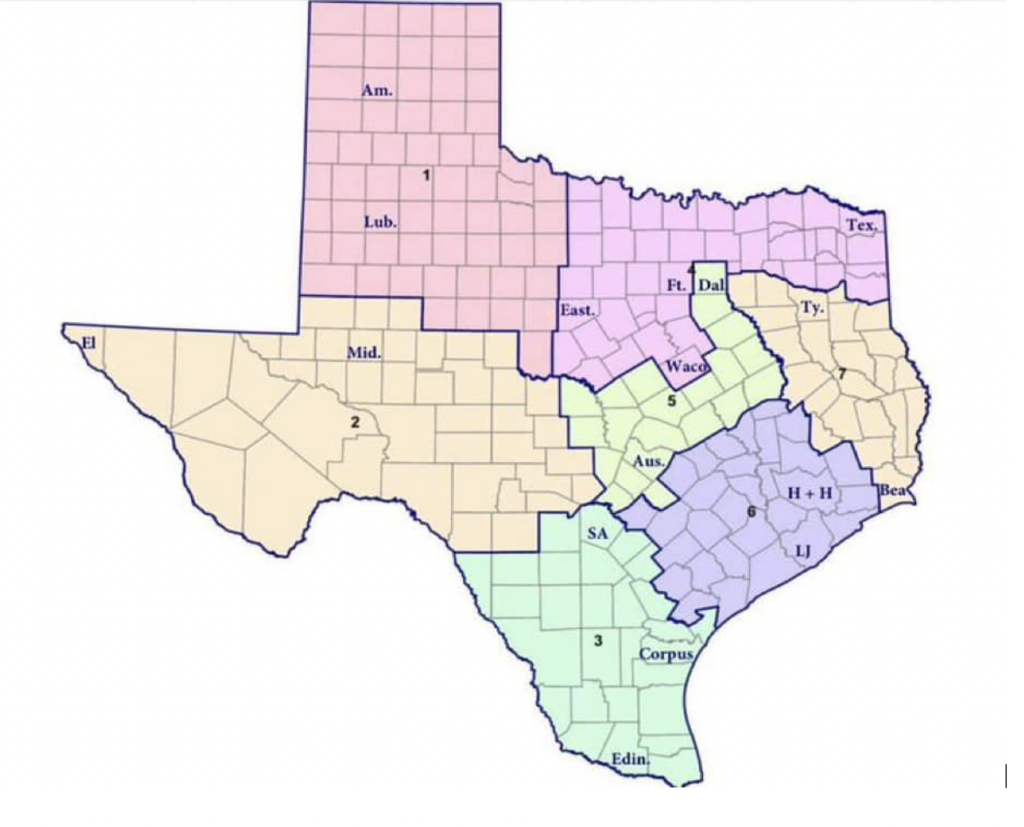

To this:

Under the new legislation, five counties in East Texas that are currently split between appellate districts (Hunt, Wood, Gregg, Rusk and Upshur) would be aligned with a single district. But those districts would themselves be realigned to create seven much larger districts.

The Dallas-based court of appeals, for instance, would stretch south and west into Austin and the Hill Country beyond. Houston’s two districts would consolidate and expand. Another district would stretch from Texarkana west into Fort Worth on to Eastland. El Paso would stretch Eastward into San Antonio and north to include Midland.

Although the legislation promises to keep most of the current chief justices in place for their current terms, all the justices would be forced into campaigns that would cover much larger geographic areas, watering down the influences of urban centers like Dallas and Houston in ways that a number of witnesses argued would clearly hurt minority representation on the bench.

Moreover, the five justices of the newly-created Texas Court of Appeals court would be elected statewide, in effect adding a layer of potentially partisan control over challenges to state agencies — and over such issues as public health, school policy or election procedures — by what would be a court dominated by Republicans.

Emily Eby, staff attorney for the Texas Civil Rights Project, said a state appeals court that would be hearing civil rights cases with judges elected at-large would have “a dramatically discriminatory effect.”

Nina Perales of Texas MALDEF said SB 11, in particular, represents “an unconstitutional dilution of Latino votes.”

Justice Erin Nowell, of the Fifth COA in Dallas, said that of a combined 80 justices on the courts of appeals in Texas, she is the only African-American. “And under this new law I would not likely be elected.”

The bills were likewise criticized in two-minute increments by the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), Texas Watch, the League of Woman Voters and others.

Beyond the question of voter dilution, more than a few critics questioned whether the proposals would solve problems or create them.

Chief Justice Darlene Byrne of the Third Court of Appeals said the additional layer of a state appeals court seems redundant. By statute, the Third COA already has jurisdiction over many agency-related cases. All cases originated by the attorney general go through Travis County. And there just aren’t that many of them, she said.

“By our calculation, there are only about 94 cases annually that are reviewed by our court,” she said. “If that rose to 108 cases that would still be only 20 cases handled by each justice (of the proposed five) each year,” she said.

Chief Justice Bonnie Sudderth of the Second Court of Appeals, spoke on behalf of all 14 COAs. She said a wholesale reformation of the state appellate system will overload a system that is forced to deal with Covid-19 restrictions, the lingering effects of a statewide ransomware attack and a likely explosion in caseloads within the next 12 to 24 months.

“It’s not just the justices who will suffer, but the citizens of this state,” Sudderth said.

Justice Gisela Triana, also of the Third Court of Appeals, questioned whether the proposals would solve any of the conflicts cited by Huffman. Adding in the proposed chancery business courts and would create 18 courts, she said. “That wouldn’t solve the problem; it would exacerbate it.”

Some found the legislation remarkable, both for the sparseness of its content and its lack of readily available statistical support.

“The integrity of the process is flat-out offended by this bill,” said Marshall Wood, president-elect of East Texas ABOTA (American Board of Trial Advocates).

Having listened to several hours of criticism Sen. Huffman tried to assure the committee that much thought had gone into the legislation.

At her request, David Slayton, director of the Office of Court Administration, testified that his office had provided Sen. Huffman with statistics that suggested ways to balance such factors as inter-district case transfers and docket caseload. Sen. Huffman said she and the committee’s lawyers drew the maps based on that data.

She said all 14 chief justices were informed of the process. “We had a Zoom meeting,” she said.

“Did you consider census data?” asked Sen. Hinojosa.

“We used data from the court, not census data,” Sen. Huffman said.

“Did you consider partisan implications?” asked Sen. Johnson.

“Absolutely not. We considered only the case filings,” Sen. Huffman said.