© 2017 The Texas Lawbook.

By Jeff Bounds

New patent lawsuits fell in the Eastern District of Texas in the first half of 2017, with a key ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court ushering in a new era for the place America has gone to settle disputes about inventions.

Patent owners filed 604 infringement suits in the Tyler-based based district between Jan. 1 and June 30, down nearly 21.3 percent from 767 in the same period last year, according to Lex Machina, a California-based supplier of legal data.

In a May 22 opinion in TC Heartland vs Kraft Foods, a unanimous Supreme Court said patent cases must be filed where defendants have a “regular and established place of business,” as laid out under a long-standing statute, 28 USC 1400(b).

That reversed a 1990 ruling from the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals in VE Holding vs Johnson Gas Appliance, which had allowed the suits to be filed most anywhere.

“The decision in TC Heartland has caused me to pause in filing a couple of new cases to ensure we’re getting the correct venue,” says Charles Baker, a partner in the Houston office of Locke Lord. “Before, all you really needed to worry about was whether an infringing product was sold or offered for sale in that judicial district.”

To avoid venue disputes, plaintiffs are shifting to places like the District of Delaware, where many companies are incorporated, experts say. Based in Wilmington, the district saw a 71.1 percent jump in first-half patent cases, from 201 to 344, Lex Machina data shows.

It is also likely that the Central and Northern Districts of California will see more cases, as many technology companies are based there, experts say.

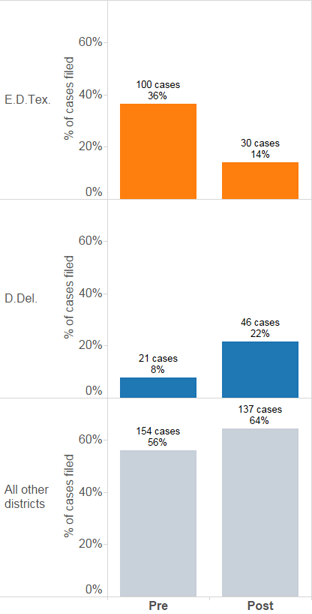

The Eastern District’s share of new patent cases was low in the weeks after the TC Heartland decision, while Delaware and other districts got a greater percentage, Lex Machina data show.

The early view is dramatic. In the 21 days prior to TC Heartland, the Eastern District of Texas accounted for 36 percent of the 275 patent disputes filed nationwide. Of the 213 patent cases filed in the 21 days after Heartland, the EDTX share dropped to 14 percent, Lex Machina data shows.

TC Heartland may also accelerate an on-going exodus from East Texas courts of “non-practicing entities,” or NPEs – businesses that enforce patents they don’t use in the production of goods or services. These operations are sometimes known by a pejorative label, “patent trolls.”

By one measure – plaintiffs who have filed at least 10 patent cases within a 365-day span – Lex Machina found these “high-volume plaintiffs” make up a disproportionately large share of both East Texas and Delaware dockets at a given time.

A decline in Eastern District cases usually corresponds with an increase in high-volume plaintiff cases in Delaware, and vice versa. Similarly, these patent owners account for most of the spikes and dips in the two districts’ new patent cases, Lex Machina’s analysis shows.

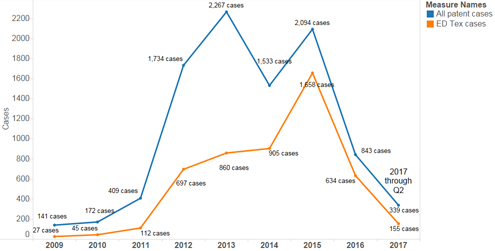

Using a slightly different measure of high-volume plaintiffs’ infringement claims (see chart) 1,658 cases were filed in East Texas in 2015, out of 2,094 nationwide that year, Lex Machina says. During the first half of this year, only 155 such cases were filed in the Eastern District and 339 nationwide.

What now, big cities?

Changes in East Texas may create uncertainty for intellectual property practices in large firms that handle patent litigation.

The flip side is that Texas litigators are getting pulled into far-flung locales to handle patent squabbles.

“Our practice has become practically borderless,” says Demetrios Anaipakos, a Houston-based shareholder at Ahmad Zavitsanos Anaipakos Alavi & Mensing. “Not only have we handled cases all over the United States, but also we have been actively involved in numerous significant cases in Germany and, more recently, in China.”

As experts like Smith point out, changes affecting the Eastern District have been underway for some time. While NPEs like the district’s knowledgeable and efficient judges, they now must contend with potential challenges to their patents’ validity through an administrative arm of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Cases that plaintiffs expect to litigate could end up there if their potential value is enough to offset a battle about which district should handle them.

“It also may mean more low-dollar cases against smaller and smaller defendants – cases that settle for mid- to low five figures or even less, cases that are cheaper to settle than to fight over venue,” he says.

Brushing up on venue law

A 2016 study predicted the Eastern District would rank the No. 2 district nationwide, with 14.7 percent of all patent cases, if Supreme Court made all the venue changes that TC Heartland had asked for.

Delaware, with a projected 23.8 percent, was No. 1 in the study’s rankings of districts.

Of course, the Justices carved their own path, such as by leaving extensive venue choices for those suing foreign corporations.

The study’s predictions were also based on patent suits from 2015, when 44 percent of those cases nationwide were launched in the Eastern District.

For now, lawyers and Eastern District judges alike are grappling with a paucity of case law for determining what constitutes “a regular and established place of business” in patent cases.

Patent litigation wasn’t as prevalent as today when the Federal Circuit’s VE Holding opinion threw open the venue floodgates in 1990. Judges have thus largely left the question untouched for nearly 27 years.

“We have all had to brush up on our venue law,” says Stephen Stout, an Austin-based partner at Vinson & Elkins.

Amid a flood of venue challenges, Eastern District Judge Rodney Gilstrap on June 29 laid out a four-factor test for determining the appropriate districts for given patent disputes. Gilstrap’s opinion is viewed in some quarters as favorable to patent owners.

In his opinion in Raytheon Co. vs. Cray Inc., Marshall-based Gilstrap – by far the nation’s busiest patent judge – said venue should rest on the extent to which the defendant:

1. Has a physical presence in a district, such as property, inventory or people;

2. Represents internally or externally that it has a presence in a district;

3. Receives benefits from its presence in the district, such as through sales revenue;

4. Interacts in the district in a targeted way with parties such as potential customers or users.

The decision is just one of several attorneys are following closely, according to Richard Whiteley, a Houston-based partner at Bracewell.

“Our impression is that most patent litigators are watching for decisions concerning follow-up to TC Heartland, including interpretations of the meaning of ‘regular and established place of business,’” he says.

Gilstrap’s order is not binding on other judges, who can do what they believe is right under the federal statute governing venue in patent cases, Breedlove notes.

Indeed, a week before Gilstrap’s decision, a San Antonio judge, Fred Biery, dismissed a patent case even though the Kansas-based defendants had contacts with the state that earlier might have passed muster for venue purposes, experts say.

The defendants in LoganTree vs. Garmin were authorized to do business in Texas as non-resident corporations, and their web site provided viewers a list of distributors that handled their products in the San Antonio/Austin area, court documents say.

Goodbye to administrative review?

In another ruling with potential implications for the Texas intellectual property bar, the Supreme Court will hear arguments this fall about the constitutionality of certain administrative patent reviews.

Called “inter partes reviews,” the proceeding is a means by which outside parties can challenge, and potentially kill off, patents owned by others.

Dallas is one of four U.S. cities with satellite locations of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, which conducts inter partes proceedings through an arm called the Patent Trial and Appeal Board.

The case the U.S. Supreme Court will take up in their next term, Oil States Energy Services v. Greene’s Energy Group, pits two Houston companies in a battle over whether such reviews should be conducted by Article III courts.

“The case will likely turn on whether a patent is viewed as a private property right,” says Marc Hubbard, a Dallas lawyer and adjunct professor of clinical law at Southern Methodist University.

Hubbard won’t be surprised if five conservative Justices rule that inter partes reviews are unconstitutional.

“Such an outcome could give impetus to another round of legislative changes to the patent system, perhaps including more than just a replacement for inter partes reviews,” he says. The reviews were created through a 2011 law, the America Invents Act.

The constitutional argument over inter partes reviews is “anything but frivolous,” says Emerson of Haynes and Boone. “And public-rights doctrine is an interesting and somewhat arcane area of the law. This will be very interesting.”

© 2017 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.