© 2014 The Texas Lawbook.

By Mark Curriden – (July 30) – When the U.S. Supreme Court told the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit to reconsider its decision that the University of Texas’ race conscious admission policy was constitutional, legal and political analysts predicted the lower court would quickly strike down the school’s diversity effort.

After all, the Fifth Circuit is widely considered the most conservative federal appeals court in the country – a court where Republican-appointed judges outnumber Democratic jurists two to one.

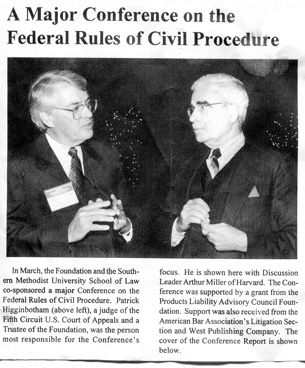

Enter Judge Patrick Higginbotham, appointed by President Reagan and once a conservative favorite for the Supreme Court. For months, Higginbotham studied UT’s admissions program and its statistical results. He examined Supreme Court precedents and the legal briefs filed in the case.

On July 15, Higginbotham issued his new opinion: UT’s race conscious program is legal because it is a narrowly tailored part of the university’s more holistic approach to student admissions.

In a 41-page decision that legal experts describe as a “legal masterpiece,” the judge provides the most detailed analysis ever of the legal, historical and public policy issues surrounding race and university admissions. Just as importantly, they say, the ruling offers a clear guide to public colleges across the country in how to develop and implement a legal race conscious admissions program.

“It was a brave decision,” says Charles Matthews, the former general counsel of Exxon Mobil and a long-time friend of Judge Higginbotham. “This case is another example of Pat laying out a roadmap for the future. He again demonstrated that he has no political agenda.”

“Pat has a cowboy common sense about life and he brings that common sense to being a judge,” says Matthews, who owns a ranch near Higginbotham’s ranch in Blanco.

Higginbotham has authored more than 400 opinions during four decades on the federal bench – the last 32 years on the Fifth Circuit, which decides the most important federal civil and criminal disputes in Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi.

His decisions have redrawn Congressional election maps to make them fairer to minority voters, transformed securities litigation, altered bankruptcy proceedings for individuals and businesses, expanded religious liberties, upheld state restrictions on abortions and favored some federal laws limiting gun sales.

His opinions have blasted Texas judges for their mishandling of death penalty trials, slammed his fellow Fifth Circuit judges for not giving more deference to jury verdicts and broken new ground by ruling for the first time that Texas judicial elections were governed by the federal Voting Rights Act.

“Judge Higginbotham’s opinions have impacted nearly every individual and every business in Texas,” says Marianne Auld, an appellate law expert at Kelly Hart & Hallman in Fort Worth. “His influence is far-reaching. He’s written groundbreaking opinions on nearly every aspect of law. Judges across the country cite his opinions.”

David Coale, a partner at Lynn Tillotson Pinker & Cox in Dallas, says Higginbotham, who turned 76 this year, has already established himself as one of the most important appellate judges in American history.

“The UT case, in a capsule, demonstrates the fearlessness, brilliance and independence of Pat Higginbotham,” says Coale, whose practice specializes on Fifth Circuit appeals. “He deftly balanced legal precedent, empirical data, and the practical realities of running a big university.”

Coale says Higginbotham took the time to actually understand the nuts-and-bolts of the UT admissions policy, to explain the statistical necessity of the race-conscious effort and to detail the specific results it has produced.

The opinion is effective, he says, because the judge was able to show that highly qualified whites and non-whites benefit under the UT plan.

Higginbotham wrote that UT’s policy allows the university “to reach a pool of minority and non-minority students with records of personal achievement, higher average test scores, or other unique skills” that it otherwise would not attract.

Then, the judge forcefully reminded the Supreme Court, which might decide to review his opinion, of its own prior decisions.

“It is equally settled that universities may use race as part of a holistic admissions program where it cannot otherwise achieve diversity,” Higginbotham wrote. “This interest is compelled by the reality that university education is more the shaping of lives than the filling of heads with facts — the classic assertion of the humanities.”

Lawyers repeatedly comment on how humble and approachable Higginbotham is, which is not something that can be said about many federal appeals court judges. Close friends point to his childhood as a foundation for his views on life and the law.

Humble Beginnings

Patrick E. Higginbotham was born in 1938 in rural Alabama. His father was a dairy farmer who struggled to make ends meet. As a kid, young Pat sold collard greens from the back of the truck to earn extra cash.

When he was 12, the town built a tennis court, which captured Higginbotham’s attention. He traded his hunting knife for a tennis racket and moved into the YMCA when he was 14 to focus on playing tennis. He was good, earning a scholarship at the University of Alabama from its athletic director, legendary football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant.

“Pat grew up poor and knows what it means to have a tough upbringing,” says long-time friend Jim Coleman, a partner at Carrington, Coleman, Sloman & Blumenthal in Dallas. “That experience is part of his character and made him the man and father and judge he is today.”

“Pat grew up poor and knows what it means to have a tough upbringing,” says long-time friend Jim Coleman, a partner at Carrington, Coleman, Sloman & Blumenthal in Dallas. “That experience is part of his character and made him the man and father and judge he is today.”

Higginbotham finished college and law school in just five years. At age 22, he joined the U.S. Air Force JAG Corps, where he tried his first case – a criminal theft matter.

Following the military, he moved to Dallas to join the city’s oldest law firm at the time – Coke & Coke, where he specialized in antitrust litigation.

“I marveled that people would pay me to have so much fun,” Higginbotham says. “The practice of law was a lot different back then. We didn’t keep timesheets until 1966 because no one ever thought about billing by the hour. A partner leaving his or her law firm for another law firm over money was simply unheard of.”

In 1975, President Ford nominated Higginbotham to the U.S. District Court in Dallas, making him the youngest federal judge in the country at the time.

He was so young that many of the older lawyers who practiced in his court called him “Judge Pat” for years, but it was clear to all of them early on that “Judge Pat” was going to be a significant force on the bench.

Fraud on the Market Theory

The national spotlight first cast on Higginbotham in 1980. The federal judiciary consolidated eight large securities fraud class action lawsuits filed across the country and sent them to Higginbotham to handle.

Scores of shareholders of Dallas-based LTV Corporation, a diversified holding company with revenues of $7 billion, sued the company after LTV issued a restatement of three years of earnings and its stock price plunged.

In determining whether the plaintiffs relied on LTV’s alleged misrepresentations, Higginbotham issued a groundbreaking opinion on the “fraud on the market” theory in which he cited some of the nation’s leading economic experts.

Higginbotham wrote that the “presumption” that investors rely on a corporation’s misrepresentations as part of the information presented by the marketplace is based on “common sense and probability.”

When LTV appealed to the Fifth Circuit, a three-judge panel issued this per Curiam decision:

“The issues raised in this case are complex, and at first glance, confusing, but the district judge did an admirable job of sorting out and resolving the complexities. The district court’s findings are errorless and its conclusions of law comport fully with our conclusions. We therefore adopt Judge Higginbotham’s opinion as our opinion on appeal.”

The Supreme Court later adopted Higginbotham’s specific language.

In 1982, President Reagan promoted Higginbotham to the Fifth Circuit, which, at the time, was packed with moderate and more liberal leaning judges. Legendary jurists, including Minor Wisdom, Elbert Tuttle and Frank Johnson, had steered the New Orleans-based appeals court to the left throughout the civil rights movement. President Carter’s eight appointees kept it left of center.

“I was privileged to have Judge Wisdom take me under his wing and guide me,” Higginbotham says. “It was an honor to watch him in action and see his mind at work.”

Higginbotham was a frequent dissenter in those early years, but eight appointments by Presidents Reagan and George H.W. Bush pushed the Fifth Circuit toward a considerably more conservative bent. Then President George W. Bush nominated six more judges and the Fifth Circuit became known as the most conservative federal appeals court in the nation.

“When I joined the Fifth Circuit, I may have been the court’s most conservative judge,” he says. “Now, I’m probably left of center, even though I don’t think I’ve changed my views at all.”

But he is in the majority a whole lot more often.

Fifth Circuit Chief Judge Carl Stewart, in an interview, said that’s because there is no judge who is more influential on the appeals court than Higginbotham.

“He has so much experience in so many different subject matters that there’s hardly a case that ever comes before us that he’s not already faced,” Stewart says. “He brings so much perspective and he’s a scholarly student of the law. He knows it like the back of his own hand.”

In 1990, Higginbotham made national news again when he authored a landmark opinion that the federal Voting Rights Act also applied to judicial elections in Texas. He wrote that state judges are “representatives” under the federal law and that there is a “linkage” between the judge’s jurisdiction and those who elected him or her to office.

In 1990, Higginbotham made national news again when he authored a landmark opinion that the federal Voting Rights Act also applied to judicial elections in Texas. He wrote that state judges are “representatives” under the federal law and that there is a “linkage” between the judge’s jurisdiction and those who elected him or her to office.

The Fifth Circuit initially rejected the judge’s argument, but the Supreme Court reversed it and adopted Higginbotham’s view as the law of the land.

“I’m actually not as confident as I used to be that I’m right, and that’s because I am sensitive to my own faults and limits,” he says. “But it is always nice when your peers and the justices in Washington recognize your hard work.”

Problems with the Death Penalty

Higginbotham says death penalty cases continue to bother him – not because he’s anti-capital punishment (he’s voted to uphold four times more death sentences than he’s voted to overturn), but because he believes the courts need to go the extra mile to make sure the defendant gets a fair trial.

As a result, he’s voted to reverse the death penalty in cases where defense lawyers slept through portions of the trial, came to court drunk or did very little work on their client’s case. He blasted prosecutors for withholding evidence and allowing witnesses to fabricate testimony.

Even fellow judges have not been immune to the sharpness of his pen.

In 2008, Higginbotham blasted Texas judges in an opinion reversing the death sentence of a North Texas man after the state judges refused to hold an evidentiary hearing about the potential mental health of the defendant.

with Jim Coleman

“The life and death of a defendant, determined without hearing cross examination to resolve disputed material facts, here violates the core principles of due process,” Higginbotham wrote. “Judges in each step of the case… decided they could sort through the complicated scientific evidence and conflicting lay opinions themselves, without the aid of adversarial truth-seeking.”

In an effort to be proactive, Higginbotham took a lead role in the development of the Center for American and International Law in Plano, an educational institute that has trained more than 600 lawyers and judges on death penalty trial procedures.

“If you really support capital punishment, you need to support competent lawyers and judges,” he says. “We make enough mistakes when all three legs of the stool [prosecutors, defense lawyers and judges] are strong, but if one or two legs are weak or incompetent, then a fair trial is nearly inconceivable.

“I would not be surprised if the death penalty goes away,” he says. “I’m not sure people support committing the necessary financial resources to make sure the process is fair.”

Vanishing Jury

But no legal or public policy issue concerns Higginbotham more than the decline in civil jury trials. The number of jury trials in civil disputes has declined more than 60 percent during the past two decades. He points to tort reform, the rise of arbitration and decisions by his peers to undermine the role and authority of citizen juries.

“There are elitists in our society who do not trust citizen juries,” he told The Dallas Morning News in an interview in 1999.

“Judge Higginbotham really respects jury verdicts and he is very reluctant to set aside the decision of jurors unless the record requires that he does so,” says Houston trial lawyer David Beck at Beck Redden.

In 2009, Higginbotham authored a scathing dissenting opinion in a medical malpractice case in which a majority of the Fifth Circuit reversed a $3.5 million jury award.

Higginbotham said the majority’s decision “delivers a gross injustice” to the plaintiffs and explains why there are so few trials.

“There is an abandonment of judicial roles when judges allow their private view on jury trials and the divisive issues of health care to guide their judicial hand,” he wrote.

“There is an abandonment of judicial roles when judges allow their private view on jury trials and the divisive issues of health care to guide their judicial hand,” he wrote.

“Trials of civil cases are disappearing in federal courts,” he continued. “Much is being written about this phenomenon and why it is occurring. To those students, I say: Read this case.”

Higginbotham says he feels sorry for some lawyers who get nervous at oral arguments and experience brain freeze. Other lawyers, he says, make the mistake of having too much fun the night before oral arguments in New Orleans.

“There was this one lawyer from Mississippi who stood up to make his argument and he was gripping the podium very tightly,” Higginbotham says. “The lawyer began leaning backwards and just kept going, falling over backwards, completely passed out.”

Fellow Fifth Circuit Judge Henry Politz jumped over the bench, rushed to the man’s side, unloosened his tie and got the man to regain conscience.

“The man looked up at Hank and immediately fell unconscious again,” Higginbotham says.

“Oh hell, Hank, he woke up, saw you and thought you were going to kiss him and passed out again,” Higginbotham said.

The judge says he has seen his fair share of cases with unusual facts or bizarre claims.

Monks and Caskets

“Every day, I am amazed that they pay me money to have so much fun,” he says.

Higginbotham points to an appeal that came before the Fifth Circuit last year in which Louisiana’s state board of funeral directors ordered a group of Benedictine monks to stop selling low-cost caskets from their monastery outside of New Orleans. The regulators said that only funeral directors licensed by the state were permitted to sell coffins.

Higginbotham found the state regulation to be simply ridiculous.

“The funeral directors have offered no basis for their challenged rule and, try as we are required to do, we can suppose none,” the judge wrote in his opinion striking down the rule.

“Louisiana does not even require a casket for burial, does not impose requirements for their construction or design, does not require a casket to be sealed before burial, and does not require funeral homes to have any special expertise in caskets,” Higginbotham opined.

While the argument and the facts may be unusual and even humorous, the legal decision is one that will be taught in law schools across the country, says Coale, the appellate law expert.

“It is extremely rare for a federal appeals court to strike down a state economic regulation on due process grounds,” Coale says. “But this is a really important landmark on how that constitutional guarantee impacts economic regulation.”

Pet Peeves

Higginbotham’s pet peeve is that lawyers sometimes ignore what the judges ask during oral arguments.

“I don’t understand it when lawyers ignore my questions, as if I am wasting their time, and they just keep making their pre-determined argument,” he says. “I tell them that’s fine but you are not answering my question.”

Higginbotham says he frequently proposes hypothetical situations during arguments. He says too many lawyers respond, “Judge, those are not the facts in this case.”

“I know those are not the facts in this case, which is why I said it is hypothetical,” he says. “It can be aggravating.”

At the end of the day, legal experts say that Higginbotham’s opinion in the UT admissions case will go down as one of the most thoughtful and well-written decisions on the issue of race and education.

“When you read the judge’s opinions, you know it is his words because he uses his words so precisely,” says Auld. “You can hear his voice in his opinions. He never hides his viewpoint and you never doubt what he’s saying.

“There are certain people called to the law the way some people are called to be missionaries,” she says. “That’s Pat Higginbotham. He understand, respects and loves the law, the legal process and the players in the justice system.”

Higginbotham’s long-time friend, Haynes and Boone partner Barry McNeil, tells a great story that provides insight into the judge’s work habits and his commitment to the justice system.

The pair was scheduled to play tennis one Saturday morning at the T Bar Racquet Club. McNeil arrived 30 minutes early, at 7:30 a.m., to find Higginbotham already there, sitting in his car and vigorously writing on a notepad. He was finalizing an opinion.

“Here was this brilliant, intellectual giant and federal judge, who has every right and ability to work in a relaxed and casual manner without any deadlines or supervision, and yet, his devotion to his work and the law was such that he didn’t want to waste a single minute,” says McNeil.

“Pat Higginbotham’s whole life has been about using the law to make the world a better place,” he says. “He will go down as one of the greatest judges of all time.”

In 2013, the Center for American and International Law celebrated Judge Higginbotham’s career with a lunch program at the Dallas Bar Association. The CAIL presented an excellent video featuring friends and family.

Chief Judge Sidney Fitzwater told the 300 lawyers who attended that Higginbotham led the way for younger lawyers, including himself, to become judges.

“The common footsteps in which we all walked — the common shoulders on which we all stood — were the footsteps and shoulders of Judge Higginbotham,” Fitzwater said. “He provided the gold standard. He proved that younger judges could have not only the intellect and dedication but the wisdom and judgment to serve as members of the judiciary. And many younger lawyers who became younger judges have Judge Higginbotham to thank for making this possible.

“His impact on the Northern District bench and on the legal profession is far-reaching and probably incalculable,” Fitzwater said.

© 2014 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.