Photo credit: Houston Chronicle

HOUSTON — As Tracy LeRoy and Paul Yetter walked back to the firm’s office after lunch last August, they bumped into an appellate lawyer from New York City.

“Wait, are you the Paul Yetter of Yetter Coleman?” the New Yorker asked.

“Paul said something like, ‘Yes, I’m Paul Yetter of Yetter Coleman, but my name just happens to be on the firm. I have an amazing team, and Yetter Coleman is so much more than me,’” recalled LeRoy, a partner who had just joined the Houston litigation boutique a few days earlier.

Business leaders and lawyers say the response is typical Paul Yetter — unassuming, modest and always ready to credit success to others.

But the reason corporate leaders in Texas recognize Yetter’s name in the first place is because he’s won so many bet-the-company cases for some of the biggest companies in the state. His clients include Energy Transfer Partners, General Electric, NRG Energy and American Airlines.

As a newly-minted lawyer in the 1980s, he worked with the late Joe Jamail in the historic $10.5 billion win for Pennzoil against Texaco. A few years later, he helped defeat Jamail and famed trial lawyer David Boies in a $1 billion airline antitrust dispute.

Yetter and his legal team made headlines again this month when they won a major federal appellate decision that will make Texas’ foster care system safer for children. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit affirmed many of the reforms to the system that Yetter has long sought, including the appointment of monitors to approve the state-conducted studies on how to reduce the workload of caseworkers, and the requirement of 24-hour “awake-night” adult supervision in group homes.

Yetter Coleman – a Houston-based litigation boutique with only 36 attorneys – has battled with state officials for nearly a decade claiming that the Department of Family Protective Services routinely violated the constitutional rights of the 12,000 children in its long-term foster care system due to institutional flaws that subject them to unreasonable risks of harm.

To date, the firm has worked more than 12,500 hours on the case and invested more than $5.8 million in staff time and expenses — all pro bono. The reason the litigation has taken so long and cost so much is that Texas officials have appealed court decisions seven times during the last decade — from pre-trial orders to post-trial decisions ordering fixes to the system.

“To our knowledge there has been no state in the country who has fought more obstinately than the State of Texas against foster care reform,” said Yetter at his office in Houston’s BG Group Place. “Most states recognize they have a problem and when it gets to the forefront in litigation, they work to find some sort of agreeable resolution. Not Texas.”

Although officials said the state is still weighing its next steps in light of the Fifth Circuit’s July 8 opinion, Yetter said he is certain the Texas Attorney General’s office is not done fighting.

“They have the right to fight it, and they have fought it, so they will,” he said. “They’ve already said they will appeal it to the full Fifth Circuit, and we assume probably to the United States Supreme Court.”

The father of seven sons, Yetter said his law firm committed to take the case 15 years ago because it fit the firm’s goal of tackling a big impact pro bono case that would lead to permanent systematic changes.

“Institutional reform litigation is tough, complicated and needs a lot of resources, and we felt like we could do it really well,” Yetter said.

With Yetter Coleman’s extensive background handling large class actions and other highly complex commercial matters, the foster care case was a challenge Yetter said he felt his lawyers could handle.

“We wanted to give back to the community, and this became a glaring opportunity at the time,” Yetter said. “We were more than happy to try it out. I don’t think at the time we even realized how big of a job that would be, but we’ve never looked back. It’s been incredibly gratifying.”

Yetter has been able to pull off such a complex and tenacious battle against the State of Texas due to the approach he has developed over the past three-and-a-half decades as a high-stakes commercial trial lawyer.

“He takes very technical, complex commercial disputes and simplifies them into concepts and language that the average person who would be sitting in a jury box can understand,” said Jim Zucker, a partner at Yetter’s firm. “I think he can genuinely relate to jurors no matter what their background is, because he has remained so humble and down-to-earth.”

“He rides the bus to work every day and eats a brown bag lunch every day,” Zucker said. “He has for all his success not changed who he is.”

Another key to Yetter’s success, according to former American Airlines General Counsel Gary Kennedy, is his impeccable preparation on cases and ability to avoid the courtroom theatrics and Rambo-style tactics that many Texas trial lawyers employ.

“He is a gifted orator with impeccable judgment, born out of an understanding of every facet of the case,” said Kennedy, who during his tenure as American’s GC hired Yetter for high-stakes cases, such as a $235 million settlement it obtained against Sabre in the midst of the airline’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy. “Whatever he recommended, I knew I could trust his judgment without reservation. It made my job easy.”

“Paul’s demeanor in a courtroom is an event in itself,” added Kennedy, who is now on the board of the global investment firm Pimco. “I never once saw him elbow his way around a courtroom. He never needed to. When he’s in a courtroom, jurors want to marry him and the judge wants to take him out for a beer. He is that good.”

A West Texas Upbringing

Born and raised in El Paso, Yetter developed his affinity for the law and helping others through his father, a solo practitioner. While helping out in his father’s law office, he observed the elder Yetter take “whatever (work) came in the door” — be it writing a will, solving a personal injury dispute, setting up a small business, or something else.

To see how far Richard Yetter would go to help his clients, one would have only needed to look at the downstairs décor of the Yetter family home in those days, which was sprinkled with large, mismatched pieces of furniture given by clients who could not afford to pay Yetter’s father in cash.

“My dad has a very big heart and if you couldn’t pay, he would figure out a way to make it work for you,” Yetter said. “I watched how he could help people, which is one of the very important reasons being a lawyer made a lot of sense to me.”

For college, Yetter decided to stay in his hometown and attend the University of Texas at El Paso, where he received a bachelor’s degree in business. While there, he met Patti, his wife of 36 years.

“El Paso is a bigger town than people realize, but you have a small-town feel growing up,” Yetter said. “Economically it’s not a wealthy town, so it’s very focused on family, church, history, and the local college is the focal point of the city. The city rises and falls with their sports teams.”

Right after graduating from law school at Columbia University in 1983, Yetter moved to Houston to be with his wife, who had taken a job at Continental Airlines. He spent a year clerking for the legendary John R. Brown, a federal circuit judge best known for helping desegregate the South in the 1950s and 1960s. Brown was a member of the “Fifth Circuit Four,” a group of four judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit who wrote a series of opinions that were pivotal to the Civil Rights Movement.

“One of the lasting lessons I learned from him is that lawyers can make a difference in society on a very big scale,” Yetter said of Judge Brown. “He and his fellow judges did it not through persuasion or force; they did it through the rule of law. It’s one of the things that makes me proud of our profession.”

Becoming a Trial Lawyer

After his clerkship, Yetter started at Baker Botts, where he met another mentor.

Finis Cowan was a senior partner at Baker Botts around the time he and Yetter began working on cases together for Houston Lighting & Power Co., one of the firm’s primary clients.

Unlike many of the firm’s insurance industry clients, Cowan said, HL&P didn’t “just sometimes” take cases to trial.

“They had a very strict and firm policy that if they thought there was no liability, they would try a case no matter what,” Cowan told The Texas Lawbook. “That resulted in Paul getting the opportunity to get some very intense and beneficial training very early in his career.”

“He got to go to the courthouse and try cases, and quickly formed a reputation as one of the very best young trial lawyers in Houston,” Cowan added.

The first time Cowan and Yetter worked together closely was during a $1 billion trial involving allegations of attempted monopolization that Continental Airlines and Northwest Airlines leveled against American Airlines after it significantly cut its fares during a price war in 1992. Continental and Northwest viewed the act by American as an attempt to force them out of business. Because it involved antitrust claims, this was nothing short of a bet-the-company case. American could be hit with treble damages if it lost.

Photo credit: Houston Chronicle

To top it all off, Cowan and Yetter faced two formidable trial lawyers as opponents. Jamail, whom Yetter had worked with on the Pennzoil case, was representing Northwest and Boies was representing Continental.

“I remember that Joe Jamail was aggressive, clever and effective and David Boies was brilliant and polished, but the two best storytellers in the courtroom that the jury trusted without question were Finis Cowan and David Beck (co-counsel for American Airlines),” Yetter recalled.

Although the trial lasted four weeks, the jury deliberated for only 90 minutes before delivering a verdict in favor of American, Yetter said.

“I remember at the time as a young partner learning … that the key to being a great trial lawyer is telling a compelling story and building trust with your audience,” he said. “That’s how you win trials.”

While Cowan was the lead lawyer for American, he said Yetter, a newly-minted partner in his early thirties at the time, played a significant role in securing the win for American when he cross-examined a couple of executives from Continental and Midwest.

“It was a big surprise to a lot of people in the community,” Cowan said. “They figured with Joe Jamail and David Boies representing Midwest and Continental that American didn’t have much of a chance, but they were mistaken. It was a great victory and one in which Paul as a very young lawyer took on a major role.”

Built to Serve a Client

In 1997, Yetter reached a fork in the road. He represented a group of investors of Bre-X Minerals, a Calgary, Alberta-based mining company that claimed it had discovered a large chunk of gold in Indonesia. When the claims turned out to be false, Bre-X stock was delisted. Many investors, including some of Yetter’s clients, lost their life savings. Yetter spearheaded a class-action shareholder suit in Texas to recover investors’ money.

Then, Bre-X filed for bankruptcy. It became apparent to Yetter that he would have to go after other players involved who had deeper pockets.

One of them was JP Morgan, an institutional Baker Botts client. Yetter faced a choice: drop the client and continue enjoying job security at one of Texas’s most prominent law firms, or take a risk and hang up his own shingle to continue representing the investors.

“I was not comfortable leaving the client, so I left the firm,” Yetter said.

He started the litigation boutique Yetter & Warden with David Warden, a friend and Baker Botts colleague who had already left the firm.

Yetter won the case against Bre-X, and with it, more wins followed at his firm.

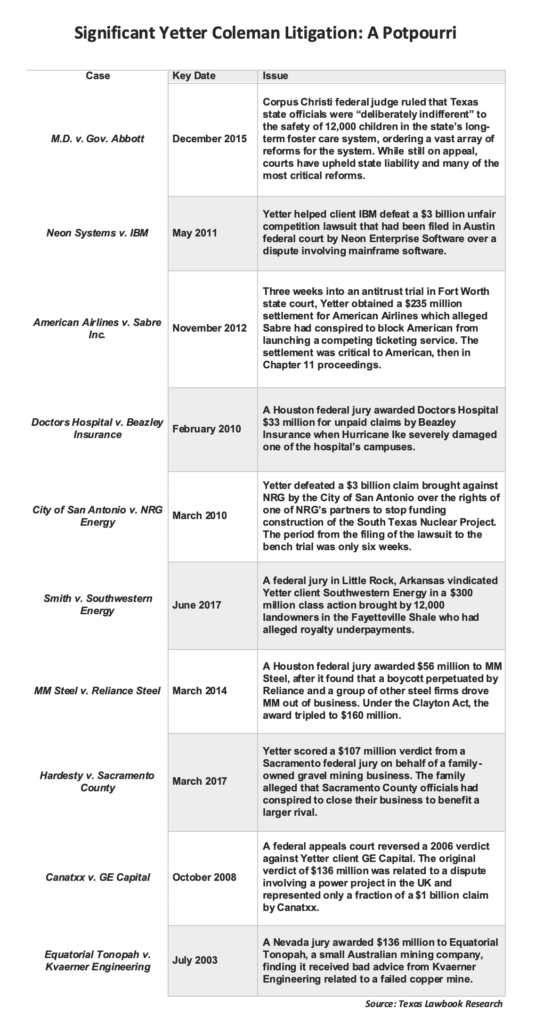

In 2003, Yetter secured a $136 million verdict for Australia’s Equatorial Mining Limited against an engineering company for providing bad advice on a failed copper mine. And while a jury hit Yetter’s client, General Electric Capital, with a $136 million verdict in 2006 in a dispute over a power project in the United Kingdom, it was a fraction of the $2 billion at stake. Two years later, an appeals court reversed the verdict into a take-nothing judgment, thanks to the work of appellate partner Gregory Coleman.

Coleman’s arrival at the firm in 2007 allowed the firm’s success to reach new heights. He brought a team of lawyers with him and launched the law firm’s appellate practice in Austin, giving Yetter Coleman the ability to serve clients in both trial and appeals courts across the state and nation, including the U.S. Supreme Court.

Coleman, a former clerk for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, served as the first Solicitor General of Texas and was once rumored to be a potential judicial nominee for the Fifth Circuit.

But in 2010, the firm faced an unexpected tragedy.

Yetter received a call two days before Thanksgiving. Coleman, a licensed pilot, had been flying a plane to a Thanksgiving family gathering when it crashed on the approach to an airport in Destin, Florida. A couple family members were with him. No one on board survived.

“Everybody was shocked. Paul made a lot of personal sacrifices to keep the firm together during a really tough time,” Zucker said. “Nobody left the firm for more than a year, which would have been easy — particularly for the appellate people — to go somewhere else. But everybody stuck together and pulled through.”

Yetter helped get the appellate practice back on its feet after recruiting Reagan Simpson from King & Spalding in July 2011 to lead the group.

Around that time Finis Cowan abandoned a quasi-retirement to join Yetter’s firm.

“He asked me and I said yes,” Cowan recalled of his decision to join. “I just thought it was a great firm and a great bunch of people to work with.”

Constantly in the Courtroom

Today, the litigation boutique that Yetter began “with no plan or forethought” remains busy at a svelte three-dozen attorneys.

“We existed to serve some clients that needed us, and that’s exactly what we’re doing here today,” Yetter said. “We have a tremendous team that is very collaborative and hard-working. Lots of the lawyers are much smarter and more effective than me, which is a joy — which is why I enjoy coming into work every single day.”

While the amount of talented lawyers at the firm has grown, the foundation of Yetter Coleman has remained the same, Yetter said.

“When I left Baker Botts, I did commercial litigation and fairly high-stakes work, and that’s what we’ve done from day one of this firm,” he said. “We do a whole lot more of it today than we did on day one because we have lots of other really good people doing it.”

The firm has made some notable lateral hires recently from the Big Law world.

LeRoy, an oil and gas litigator, headed the litigation practice at Sidley Austin’s Houston office before joining Yetter Coleman. She recently scored a pro bono win for the Houston SPCA in litigation related to the rescue of a herd of mistreated horses known as the Conroe 200.

Last January, IP litigator Jeff Andrews joined from Locke Lord. Andrews has represented big names like Baker Hughes and General Electric in IP cases and helped score a win for the University of Houston in a trademark infringement dispute it launched with South Texas College of Law, which had changed its name to Houston College of Law.

And in 2016, the firm added Andrews Kurth partner Tim McConn, a respected energy litigator. McConn is currently representing Cheniere founder and former CEO Charif Souki, who is headed to trial early next year against Cheniere in a high-profile case that — depending on who you ask — involves trade secret misappropriation, breach of fiduciary duty, or the theft of a lucrative project.

In addition, the firm added three women to its associate ranks: Myra Siddiqui, a Harvard Law grad; Heaven Chee, a former clerk for U.S. District Judge George Hanks; and Amy Heard, a former clerk for Texas Supreme Court Justice Debra Lehrmann.

Yetter said the firm has about a dozen cases slated for trial throughout the rest of the year.

At the end of the summer, Yetter and law partners Bryce Callahan, April Farris and Collin Cox will represent the FDIC in a federal securities battle against Deutsche Bank in Austin federal court.

This fall, a team led by Zucker will take an intellectual property dispute to trial in Houston federal court against Halliburton on behalf of Legacy Separators, a small oilfield tool supplier based in Oklahoma City.

Also this fall, Yetter, Callahan and associate Wyatt Dowling will wade into a trade secrets dispute involving two feuding brothers, E. Pierce Marshall Jr. and Preston Marshall, the grandsons of Houston business tycoon J. Howard Marshall II.