© 2013 The Texas Lawbook.

By Patricia Baldwin

Lifestyle Writer for The Texas Lawbook

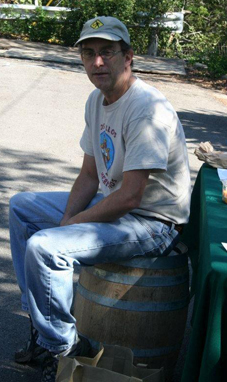

(April 4) – As a hobbyist, Pete Kennedy brews beer at home. He also has long been a fan of craft brews. So it was not surprising that, one day, the partner at Graves, Dougherty, Hearon & Moody in Austin was searching a local craft brewery’s website for locations to buy its beer. What was surprising was that he could not find the information.

Kennedy ought to know. The 50-year-old attorney first earned national attention in 1993 as the lead trial lawyer for Austin-based Steve Jackson Games in a successful lawsuit against the U.S. Secret Service, helping to establish limits on the government’s right to seize email.

He has since shaped a practice at the intersection of the law and emerging technologies, communications, intellectual property and constitutional limits on governmental regulations.

Kennedy more succinctly characterizes his practice as focusing on “disruptive market entries.”

But more on that later…

When Kennedy discovered that local craft brewers could not even tell people who were touring their facilities where to buy their products, he envisioned gathering his beer-drinking friends together to become proverbial caped crusaders in a battle to change a “silly rule.”

Then he discovered he wasn’t the first to have such an ambition. Austin attorney Jim Houchins of Houchins Law already had filed a lawsuit about another “silly rule” that labeled craft brew products according to alcoholic content, creating an arbitrary definition of styles.

Thanks to happenstance and the legal grapevine, the two attorneys met and realized they had complementary expertise. Houchins was knowledgeable about the industry; Kennedy had experience with First Amendment issues. They joined forces on behalf of several clients.

“The fact that Pete was a homebrewer added a dimension,” Houchins says. “Texas laws have been restraining the industry.”

The result: In late 2011, Judge Sam Sparks of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas declared the statutes and Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission rules in question as unconstitutional and invalid. The ruling allowed beer to be labeled “beer,” and ale to be labeled “ale,” and so on, regardless of the alcohol content. Also, as a result of the ruling, breweries and distributors were no longer prohibited from independently telling consumers where their products could be purchased.

“We felt very lucky to have the expertise and services of someone who not only had a mastery of our constitutional challenges, but also understood the nature of our business and our culture as small brewers in Texas,” Stuffings comments. “There isn’t actually that huge of a leap between homebrewing and craft brewing, so we felt very comfortable being represented by a fellow brewer.”

For Stuffings, some battles have been won, but the war to expand Texas’ craft brewery industry continues. The Jester King website is closely following the progress of Senate Bills 515, 516, 517, 518 and 639 in the Texas Legislature. Craft brewers support the first four, which would allow for off-site distribution by Texas brewpubs as well as limited on-site sales by production breweries and which also would bolster the ability of small breweries to self-distribute. The craft brewers oppose SB 639, which would make it illegal for breweries to sell the right to distribute their products to wholesalers, while making it legal for wholesalers to sell those rights to one another.

Kennedy notes that he doesn’t lobby, so “I don’t keep up with all the fine details of the legislative give-and-take.”

However, he adds, “I would certainly like to see the loosening of regulation on small business.”

A flash point for the company in Austin came during the recent South by Southwest festivals when the city wrote a cease-and-desist letter to SideCar, claiming the company was involved in an unlicensed taxi service.

“This is a disruptive technology,” Kennedy says. “These guys developed new technology. Arcane regulations are not intended to regulate them.”

Another Kennedy client is LegalZoom. “I get to be a lawyer and argue that lawyers are monopolizing,” he says, adding, “Lawyers recognize their value to clients isn’t filling out forms.”

Kennedy characterizes the underlying meaning of the evolving focus of his legal practice: “I’ve finally gotten away from ‘he’s a First Amendment lawyer.’”

Kennedy downplays his talents as a homebrewer, noting he only started about six years ago with a basic kit called “Mr. Beer.” In the past four years, however, he has become more sophisticated and serious in his hobbyist pursuit. Last fall, at a neighborhood “Yaktoberfest,” he took top honors in a casual competition with two of his beers, which are named for characters in the AMC television series “Breaking Bad.” Heisenberg IPA won first prize; Fring’s Porter took second.

Now, a family tradition required a special beer for Easter. The 2013 selection was Mexican Chocolate Irish Stout.

And, for Kennedy, “homebrewer” might be better phrased as “backyard brewer” since the smell of hops can be “very rich” for indoors, he says. He likes to combine an afternoon of boiling such brewing ingredients as barley, hops and water with cooking a brisket in his smoker.

Other steps for the homebrewer include cooling, fermenting, priming, bottling, aging – with the beer, depending upon style, ready to drink in about six weeks. Kennedy says the typical batch is five gallons.

If he’s not drinking his own brew, Kennedy has a short list of favorite local brewpubs, including Banger’s Sausage House & Beer Garden, Pinthouse Pizza, Drink Well, Hopfields…and so on. After all, as Kennedy points out, “It’s Austin.”

Do you have a special hobby – or other lifestyle interest – to share? Please email patricia.baldwin@texaslawbook.net.

© 2013 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.