It’s been four years since Randy Johnston was hired by former Navy SEAL Matthew Bissonnette, the author of the controversial book No Easy Day.

In a lawsuit version of “Planes, Trains and Automobiles,” Johnston has shuffled across two federal courts 650 miles apart, fought numerous motions to dismiss – and now, a large summary judgment motion and battle to discredit an expert witness.

In a lawsuit version of “Planes, Trains and Automobiles,” Johnston has shuffled across two federal courts 650 miles apart, fought numerous motions to dismiss – and now, a large summary judgment motion and battle to discredit an expert witness.

Johnston has exerted all of this effort for perhaps the worthiest cause of his already successful legal malpractice career: clearing Bissonnette’s name.

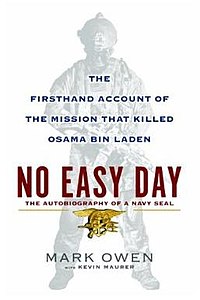

In 2012, Bissonnette published his first-hand account of the raid that resulted in the death of Osama bin Laden. But Bissonnette found himself at the center of civil and criminal investigations because he published the book, No Easy Day, without pre-publication review by the Pentagon.

He only did so, he alleges, because his lawyer advised him he was not legally obligated to do so.

Johnston says the faulty legal advice caused his client immeasurable harm. He went to bed nearly every night for four years wondering if he would be criminally indicted for treason. He lost $6.66 million in royalties that he had planned to give to charity. And, once the controversy was revealed, he was “vilified” by the press.

Earlier this month, a federal court in Indiana ruled that Bissonnette will get to argue his malpractice claims before a jury. The trial has tentatively been set for Nov. 29, according to Johnston.

“There has been so much written about him by people who do not know the facts. It is going to be a professional delight to set the record straight.”

— Randy Johnston

In a 45-page opinion, U.S. Magistrate Susan Collins cleared the way for a trial, denying motions by Bissonnette’s former lawyer Kevin Podlaski, and his former law firm, Carson Boxberger. The defendants had argued that the statute of limitations for Bissonnette’s claims had already expired and that Bissonnette failed to provide sufficient evidence to show that Podlaski was the source of the damages he suffered.

“The court is persuaded that a reasonable fact finder could conclude – without engaging in undue speculation – that Podlaski proximately caused Bissonnette to forfeit royalties to the government,” Judge Collins wrote. “Defendants, by insisting that all the evidence of record is too speculative, are ‘throwing sand’ in the court’s eyes to avert its attention. Therefore, defendants’ speculation arguments fail.”

New York lawyer Richard Simpson, who is leading the case for for Podlaski and Carson Boxberger, declined to comment. Podlaski is currently practicing at Indiana law firm Beers Mallers Backs & Salin.

“This American hero will now get his day in court and will finally be able to show his extensive efforts to comply with all his obligations of confidentiality,” Johnston said on the opinion. “There has been so much written about him by people who do not know the facts. It is going to be a professional delight to set the record straight.”

Johnston said he feels “a great deal of weight” representing Bissonnette.

“In my over 40-year career, I consider it to be one of the three most important cases I’ve ever handled,” he said. “Candidly, I’d probably make it the most important. I know that the outcome of this trial will have a profound effect upon this guy’s future life.”

The Background

Bissonnette published No Easy Day in September 2012 under the pseudonym Mark Owen through Dutton, a publishing house owned by Penguin Group. Through his book agent, Bissonnette hired Podlaski prior to publication to review the manuscript and screen it for classified information, Judge Collins’ opinion says.

Podlaski, a former U.S. Army JAG who had previously helped a former Special Forces member publish a book, advised Bissonnette not to submit a manuscript to the Pentagon for prepublication review.

Though the book quickly became a bestseller, it was not well-received by the Pentagon. Advance copies of No Easy Day somehow made their way into the government’s hands, and days before the book’s release in September 2012, Department of Defense General Counsel Jeh Johnson sent a letter to Bissonnette stating that No Easy Day would be violating the two non-disclosure agreements Bissonnette signed while in the Navy.

Despite that, Podlaski doubled down on his bad legal advice, Johnston said.

“He hadn’t even seen the documents that the client had signed,” Johnston said. “He hadn’t visited with the government at all. He didn’t even ask the critical questions that one has to know before answering this question. He simply came out with his fanny saying, ‘Oh, you have no obligation. Don’t worry.’”

What’s worse, Johnston argues, is if there had been a prepublication review, Bissonnette could have made a few easy tweaks to address the government’s concerns.

“It is absolutely true that if he had submitted the book for prepublication review, there were some things the government would have taken out. They were, however, minor,” Johnston said.

The DoD general counsel letter marked the start of civil and criminal probes by the Department of Justice and Department of Defense. Meanwhile, Bissonnette immediately became subject to public scrutiny as well. His identity was almost immediately revealed by Fox News once the publishers announced the release of the book.

“He is on the Al Qaeda hit list,” Johnston said. “He had his children change their names so they can’t be traced to him.”

Once everyone knew Mark Owen was really Matthew Bissonnette, Johnston said the press immediately reported false critiques about him, including the idea that he was trying to profit from his service.

Aside from using some of the royalties to pay his ghostwriter and publisher, Bissonnette said in the forward of his book that he would donate the rest to six different charities that served the families of fallen SEALs, Johnston said.

The charities never saw that money, however, since Bissonnette agreed to forfeit the $6.6 million in royalties to the government as part of a consent decree that ended the DoD and DOJ investigations.

Johnston said Bissonnette decided to write the book after “everyone and their dogs” started taking credit for the bin Laden operation. Among those who took credit, Johnston said, were former CIA director Leon Panetta and U.S. Navy Admiral William McRaven, who also wrote books about the bin Laden raid with no repercussions.

“It’s fine for officers and everyone above them, but if the lowest paid members of our military who actually put their lives on the line write a book, then they get criticized,” Johnston scoffed. “Everybody was getting credit except his brothers who had risked their lives as Navy SEALS and he wanted to tell the story from the standpoint of the SEALS themselves,” Johnston said.

The Ruling

The court’s opinion appeared to reflect some of Johnston’s positions.

“Defendants correctly argue that once the book was published, Podlaski could not vet it for classified or sensitive information,” Judge Collins wrote. “Unfortunately for defendants, that does not mean there was ‘nothing [Podlaski] could have done’ in an ongoing professional capacity to mitigate or reduce the damage resulting from Podlaski’s alleged negligent advice to Bissonnette.

“To the contrary, Podlaski appears to have advised Bissonnette on how to manage the fallout from the Johnson letter by counseling him ‘do nothing except apologize and maybe donate money to charity of DoD’s choice,’ and by submitting the FOIA requests” the judge added, citing Podlaski’s deposition.

Judge Collins also declined the defendants’ motion to preclude testimony by Bissonnette’s national security expert, Mark Zaid, rejecting arguments that Zaid was not a credible expert.

Zaid, a well-known national security expert, testified that had Bissonnette undergone a prepublication review with the Pentagon, the Pentagon would have allowed publication to occur assuming he made “minor redactions and rewrites to the manuscript to clear it of any sensitive information,” the opinion says.

Judge Collins points out that Zaid, who recently held top secret/special compartment information clearance eligibility, has litigated at least 10 cases involving classification or prepublication review determinations in the executive branch.

The defendants argued that Zaid was not qualified to render his opinion on Bissonnette’s situation because he “has never been employed by or affiliated with the DoD or any government agency that would have reviewed the manuscript of No Easy Day,” the opinion says.

“Defendants discount Zaid’s entire experience advising and litigating on behalf of clients in the prepublication review process solely because Zaid has not represented or worked with the government on prepublication reviews,” Judge Collins wrote. “For a district court to require such ‘particular credentials for an expert witness is radically unsound.’ ”

False Starts

Now that a jury trial is set for November, it’s time for Johnston to buckle down for the finish line – something Johnston says he is happily obliged to do.

“The level of malpractice is beyond anything I’ve ever seen,” Johnston said.

Johnston said he got involved after being recommended by some of Bissonnette’s lawyers. He filed an initial malpractice suit against Podlaski and Carson Boxberger in November 2014, in the Southern District of New York, where the book had been published.

The defendants asked the judge to dismiss the lawsuit because the venue was improper. U.S. District Judge Jesse Furman ultimately sided with Podlaski and Carxon Boxberger and dismissed the suit in October 2015, ruling that Bissonnette lacked personal jurisdiction in New York.

Johnston re-filed the lawsuit in the Fort Wayne division of the Northern District of Indiana nearly a month later. Procedural matters moved a little more slowly in Indiana, and due to various delays, a formal motion to dismiss was not filed until September 2016. The motion was argued in June 2017 and denied two months later. The summary judgment motions tied to the current ruling were argued in February of this year.

“It took a long time to get the motions keyed up so the court could rule on them,” Johnston said.

Johnston says he’s looking forward to getting the matter before a jury.

“Right now, the Internet is kind of frozen with all the bad stuff about him because he refused to engage and rebut it due to his confidentiality obligation,” he says. “The only way the record can be set straight and his name can be cleared of the lies is if I do my job properly representing him.

“And I fully intend to.”