By Janet Elliott

Appeals court judges in Texas are increasingly hostile to jury verdicts in civil cases, especially when the jurors rule in favor of plaintiffs, according to a new study.

The report, which examined a full year of decisions in 2010-2011 by the state’s 14 courts of appeals, found that the judges on those courts reverse more than one-third of all civil jury verdicts and that they are four to six times more likely to overturn jury verdicts that favor plaintiffs than verdicts favoring defendants.

Even in non-jury cases, the Texas appellate court reversal rate of lower court judgments favoring plaintiffs was double that of decisions favoring defendants

The yearlong study, conducted by two prominent appellate lawyers at Haynes and Boone, found the Texas appellate judges have an overall reversal rate of 49 percent when they review cases that the plaintiff won in the trial court and the defendant appealed. But those same judges reversed only 25 percent of the cases in which the defendant prevailed at trial and the plaintiff appealed.

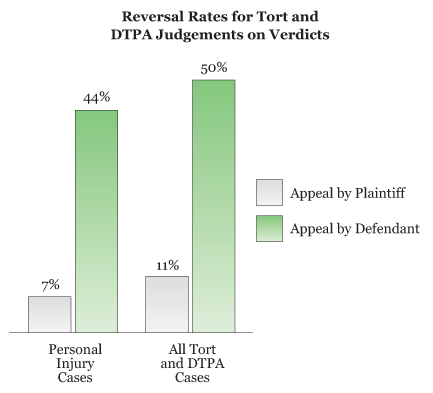

The Texas courts of appeals reversed 50 percent of the jury verdicts that favor plaintiffs in consumer fraud and general tort cases, but the judges overturned only 11 percent of the jury verdicts that favored defendants, according to the study, which is titled “Reasons for Reversal in the Texas Courts of Appeal.”

In personal injury cases, including allegations of wrongful death, the disparity was even larger. Appellate judges reversed seven percent of the jury verdicts that favored defendants, but they reversed 44 percent of the jury verdicts that decided for plaintiffs.

“It does seem to me that whether you like tort reform or you don’t, it’s worked from the standpoint of really severely limiting plaintiffs’ ability to recover in the Texas court system,” said Lynne Liberato, co-author of the study.

“It’s fair to say, they are showing less deference to juries and we see that manifested in all sorts of ways, both in the development of the law and in the attitude of some appellate judges,” said Liberato, who was chief staff attorney for the First Court of Appeals in Houston for a decade.

Liberato and Kent Rutter, who are partners in the Houston office of Haynes and Boone, reviewed 1,832 opinions issued from Sept. 1, 2010 to Aug. 31, 2011. The appellate law experts read each case and determined who had won and why. Unlike the Texas Supreme Court, which has discretion to hear appeals, the lower appellate courts must consider all that are filed.

The Haynes and Boone report reprises the law firm’s widely acclaimed 2002 study of the reversal rates in Texas’ 14 intermediate appellate courts. The 2012 findings appear in the Houston Law Review.

The new study shows that appellate courts today are more likely to reverse jury verdicts than they were nine years ago, 34 percent now compared to 25 percent then. This follows the recent report by The Texas Lawbook that the number of civil jury trials conducted in Texas has plummeted by more than 65 percent during the past 15 years.

In 2003, the state Legislature enacted significant changes limiting the amount of damages for pain and suffering that plaintiffs could recover in medical malpractice cases. They also made it more difficult for plaintiffs to prevail in product liability cases.

As a result, Rutter said, lawyers who represent plaintiffs were more strategic about picking their appellate battles, filing 39 percent fewer appeals than in the period before lawsuit reform.

By focusing on their best cases, they should have experienced greater success if everything else was equal, Rutter said.

But that didn’t happen.

“Even though they are being a lot more selective and they are appealing only their strongest cases, they still don’t have a very good track record on appeal,” Rutter said.

Liberato added that the study has a public policy aspect by showing that it’s no longer valid to blame lawyers and the legal system for economic issues such as lack of job creation.

“That’s a straw man and if that did exist, it doesn’t exist anymore, and it’s time to get off of that and look at what the real issues and real problems are,” she said.

Courts Vary in Decisions

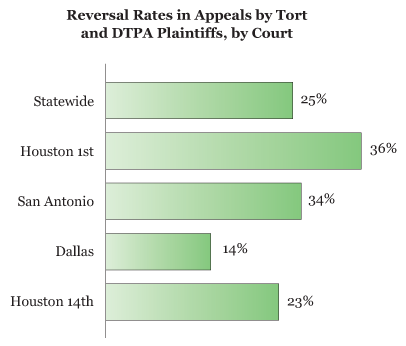

Courts that decided the most appeals brought by plaintiffs in personal injury, business and consumer protection cases were the First Court in Houston (reversal rate of 34 percent), the San Antonio court of appeals (reversal rate of 26 percent), the Dallas court of appeals (reversal rate of 14 percent), and the Fourteenth Court in Houston (reversal rate of 23 percent).

The statewide reversal rate in all civil cases – including contract disputes and family law cases — was 36 percent, a rate that the study authors call dramatic.

“Courts of appeal are certainly not rubber stamping decisions from trial judges. They are looking at each case pretty closely,” said Rutter.

Differences between the individual courts do exist, although not to the level they did in the earlier study. When all appeals are considered, the court most likely to reverse, at 46 percent, was in Corpus Christi and the one least likely to reverse, at 32 percent, was in Beaumont.

When jury verdict reversals are broken out, the variation was even more significant. For example, the Fourteenth Court of Appeals reversed 29 percent of jury verdicts, while the San Antonio court of appeals reversed 50 percent.

“We see a lot of courts of appeals reviewing a jury verdict and saying this case never should have gone to the jury in the first place,” Rutter said. “Even if a jury awarded damages, that reward is going to be reversed.”

Summary judgment appeals were the most common type of appeals. Noting that most summary judgments are granted in favor of defendants, the statewide reversal rate was 31 percent. Fact issues accounted for 47 percent of the reversals and errors of law for 35 percent. The remaining 18 percent were caused by procedural errors, a significant increase since 2001-2002 when procedural errors accounted for only 11 percent.

“In the eyes of the courts of appeals, Texas lawyers and judges are becoming less proficient or less careful when requesting and granting motions for summary judgment,” the article states.

Appeals from bench trials were reversed at a 28 percent rate. The vast majority, 81 percent, were reversed because the evidence was legally insufficient or because there was some other reason the judgment was incorrect as a matter of law.

Contract cases were reversed at a statewide rate of 32 percent, and the rates between courts did not vary widely.

In coverage disputes between insurance carriers and their policyholders, carriers were nearly five times as likely to win reversals, at 48 percent, compared to 10 percent when policyholders appealed a judgment for the carrier.

Twenty-seven percent of family law cases were reversed. Divorce cases were reversed 20 percent of the time and child support cases 35 percent of the time. While family law is the largest group of civil cases, few are tried and even fewer appealed.

Lessons for Lawyers

Jury trial results were most often reversed because the evidence was legally insufficient or the trial judge did not correctly apply the law. These reasons accounted for 77 percent of the reversals; error in charging the jury, 9 percent; and complaints about factual insufficiency, just 5 percent.

The lesson for lawyers, Rutter said, is that fights during the trial about what evidence should be admitted matter less at the appeal level than how the law is applied.

The authors said their data is a “tool to better inform the lawyer’s and client’s decision.”

“The first question our clients ask us when they hire us for an appeal, is how likely is it I’ll win, give me a percentage,” said Liberato. “We can’t really do that.”

But they can use the study to determine that reversal rate in a specific court for a certain type of case.

“It helps the client decide whether to appeal and it helps the lawyer decide which types of arguments to emphasize in the appeal,” said Rutter.

PLEASE NOTE: Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.