© 2013 The Texas Lawbook.

By Natalie Posgate

Staff Writer for The Texas Lawbook

When LynAlise Tannery applied for law school in 2008, times were still good for lawyers. Law schools promoted their job placement at 95 percent or higher. Six-figure starting salaries for new law graduates were cited as the norm.

By the fall of 2009 – Tannery’s first year at SMU Dedman School of Law – the legal job market plunged. Big law firms experienced unprecedented layoffs. More importantly for Tannery and her fellow law students at the time, firms also drastically reduced the number of new lawyers they hired right out of school.

“Most of my group of friends who graduated cum laude and higher didn’t have jobs when we graduated, and I don’t know that anybody expected that,” said Tannery, who graduated last year.

“I have some friends who are still legal interns and are struggling to find that permanent position,” she said. “My thoughts of getting a job when starting law school were definitely different from when I finished.”

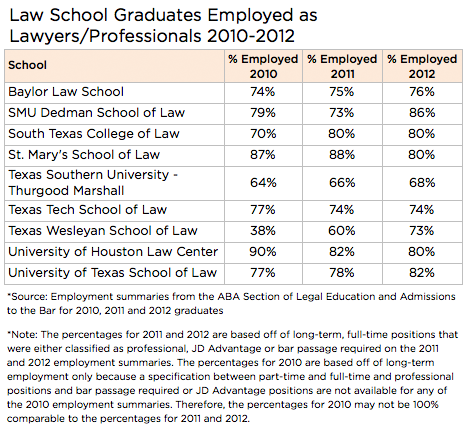

The job market for new law school graduates in Texas is slowly and modestly improving, but it still remains far tougher than before the financial crisis only a few years ago, according to new data released by the American Bar Association.

Texas’ nine law schools report that nearly 79 percent of all their 2012 graduates found permanent, full-time jobs as a lawyer or another professional position, which is three percentage points higher than 2011 but still much lower than the 95-plus percent levels that law schools bragged about in 2009 and before.

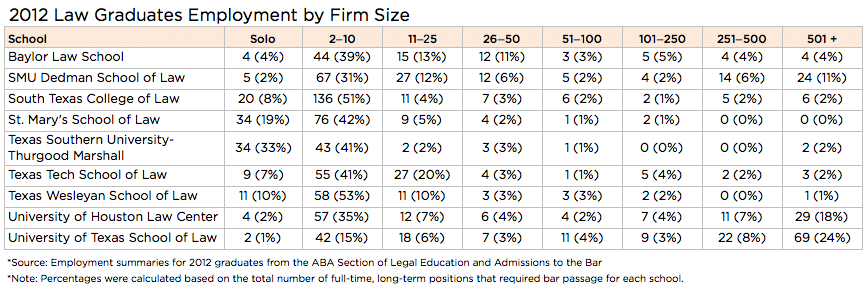

Only two-thirds of the 2,346 law graduates in Texas from 2012 found full-time permanent employment as lawyers – compared to 56 percent of law school graduates nationally, according to the ABA.

Even that number may be a little misleading. Seven percent of those listed as full-time lawyers are in solo practices, which two law deans admittedly described as law graduates who couldn’t get a job at a law firm and hung out their own shingle in desperation.

The unemployment rate for 2012 law school graduates in Texas stands at nearly 10 percent, which includes those no longer seeking a job for whatever reason. In addition, nine percent of the 2012 law graduates are listed as having temporary, part-time or unskilled jobs.

In 2012, SMU Dedman School of Law placed 86 percent of its graduates in full-time, permanent lawyer or professional positions – up from 73 percent in 2011. Fort Worth-based Texas Wesleyan University School of Law saw its job placement numbers for those same positions jump from 60 percent in 2011 to 73 percent last year. Nearly 82 percent of 2012 graduates from the University of Texas School of Law found full-time, permanent employment, up from 78 percent a year earlier.

Legal educators say they are comforted that the bleeding has stopped and the job market for new graduates appears to be recovering.

“I’d be rich if I could tell you what will happen in the years to come,” said Richard Alderman, who is interim dean at the University of Houston Law Center. “The fact that firms are moving [to Texas] creates a great marketplace for lawyers and opportunities for our students. I hope and assume that will continue.”

Cautious optimism aside, legal experts admit that the financial crisis and the decline in legal hiring exposed significant cracks in their business model and that the dynamics of their operations are changing and will need to continue to change significantly.

The high cost of legal education, which usually ranges from $20,000 to $50,000 a year or more depending on the law school, was still attractive because law schools promoted that 95 percent of their students had great paying jobs upon graduation. But following the financial crisis, the legal industry contracted and jobs dried up.

Law schools point out that some of the disparity in the numbers is because the ABA changed the job placement reporting requirements. In 2011, the ABA mandated that law schools be more transparent in the employment data they made public.

A handful of advocacy groups complained that law schools were cooking their job placement numbers by hiring some of their graduates to work temporary positions in order to get higher rankings with U.S. News and World Report. In addition, several law graduates sued their schools claiming the institutions had fraudulently provided misleading information about their job placement numbers.

For their part, law schools became much more aggressive and strategic in seeking employment for their graduates.

SMU Dedman was one of the first law schools nationally to take proactive steps to address the tightening job market. In the spring of 2010, SMU launched two programs in reaction to the economic downturn: Test Drive and Partner to Practice.

Partner to Practice allows students to clerk full-time at local law firms the summer before their final year, and matches the amount the firms decide to pay the students in tuition remission.

Test Drive allows law firms to work with new SMU Dedman graduates for two months on a “no strings attached” basis. The law school subsidizes the graduate’s salary for the first month. If the graduate and employer believe the effort will lead to a full-time, long-term position, the school will pay for a second month.

“Frankly, Partner to Practice and Test Drive were bets,” said SMU Dedman Law Dean John Attanasio. “All we were doing was getting students through the door, and betting that once they got through the door that they would get the job. The bet turned out to be right.”

Last August, Tannery interviewed for a job at Thering McCarley, a six-lawyer firm based in Frisco. She used Test Drive as a marketing tool to get her foot in the door. The firm was impressed with her skills and effort, offering her a full-time position practicing bankruptcy and family law.

“It was such a relief that I didn’t have to worry about job-hunting anymore,” said Tannery, who is 26. “I don’t know if I would have a job if it wasn’t for Test Drive. It’s made such a huge difference in my life.”

Karen Sargent, SMU Dedman’s executive director of career services, said nearly all graduates who participate in Test Drive have received offers after the two-month trial period.

A job offer for those participating in Partner to Practice is less guaranteed. The summer clerkships result in about 15 percent of those participating law students receiving job offers from the law firms, according to Sargent.

Vicki Tall, a fourth-year evening program student who will graduate this spring, came to SMU for law school after spending more than a decade working at a telecommunications company in Dallas. One of her favorite aspects of her job was handling employee-employer relationship matters, so she started law school with labor and employment law in mind.

Last summer, she was excited to clerk in the Dallas office of Ogletree Deakins, a national labor and employment firm, through the Partner to Practice program. She was even more thrilled when the firm called her in January to offer her a full-time position after graduation.

“When I got the clerkship, I was ecstatic; I just felt like I had won the lottery,” Tall said. “Then when I got the [full-time] offer, it’s a good thing I was sitting down, because I was really, really, really happy.”

Other Texas law schools have gotten equally creative.

Texas Tech School of Law has created a Regional Externship Program that allows third-year students the opportunity to spend a full semester working for a government or legal services organization in Dallas or Fort Worth while gaining academic credit.

Tech Law Dean Darby Dickerson said the school will double the number of positions next year by expanding to corporate general counsel offices and opportunities in Austin and Houston during the next two years.

“With these various components, our students are able to build a professional network in the city in which they plan to practice,” Dickerson said.

Fort Worth-based Texas Wesleyan School of Law offers a clinical program that allows students to work closely with three of the school’s in-house attorneys and represent members of the local community, according to Arturo Errisuriz, who is the assistant dean for career services.

In addition to placement efforts, law schools say that they are using other methods to help their students get jobs.

For example, Alderman of the UH Law Center said he plans to organize breakfasts with groups of alumni, and if they are successful he will start inviting students so they can network and mingle.

Schools such as SMU Dedman and Baylor Law School have expanded their career services office and hired people to explicitly seek jobs for students.

Dean Donald Guter of South Texas College of Law said the school is currently recruiting to fill an additional career services position to accomplish similar efforts to Baylor and SMU.

Guter said the number of on-campus interviews has increased this past year, which he said is generally an indication the legal market is improving.

“We’re pretty optimistic that we’ll be fine going forward,” Guter said.

Despite the better employment numbers, Errisuriz of Texas Wesleyan said he isn’t sure how long it will take for the Texas legal market to completely bounce back.

“I’m hopeful and cautiously optimistic, but I don’t see a lot of huge growth any time soon,” he said. “It will be slow.”

© 2013 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.