Chicago-based mega-law firm Kirkland & Ellis hired corporate lawyer Andrew Calder away from the competition two years ago to open the global firm’s Texas operation.

Armed with a blank check and the charge to build a first-class outpost in Houston, Calder enticed 65 attorneys to join him over the past 26 months. Another 20 are scheduled to join this fall.

Premium clients, including Dallas-based Energy Future Holdings, Houston-based Terra Energy Partners and private equity giants Blackstone Energy Partners and KKR, were signed as clients. Revenues in Texas went from zero to $64 million in 2015 and will easily pass $100 million this year, according to legal analysts.

“We have been so busy in Texas that we’ve had to bring in lawyers from other offices to meet the demand,” Calder said. “The key has been to put together a team of young, hungry lawyers who want to dominate the market in their practice areas. The firm’s goal is to be a major player in the Texas market.”

Kirkland, which has 1,700 lawyers and $2.3 billion in revenues in 17 offices worldwide, is Exhibit A in a seismic shift that is underway in the Texas legal market – a shift that is radically changing the practice of corporate law in the state forever.

A new Texas Lawbook study of legal industry finances in Texas shows that elite, wealthy corporate law firms – most of them based outside of the state – are achieving enormous financial success by stealing the best lawyers and the highest paying business clients away from large, full service legacy Texas law firms.

At the same time, dozens of national and regional law firms, including many that focus on upper middle market corporate clients in the healthcare, manufacturing, retail, technology and transportation sectors, have expanded into Texas and captured more than $1 billion in legal fees from long-time indigenous law firms in 2015 alone.

As a result, many old-line traditional Texas law firms that once dominated the state are fighting for survival as their market shares plummet. They are almost helpless as their best young talent flees to wealthier competition and long-time clients shift their allegiances to the elite firms.

“A generational shift in the legal marketplace in Texas is taking place,” said Rob Walters, managing partner of the Dallas office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, which is one of those elite national firms. “The legal market is separating the ‘have’s’ from the ‘have not’s.’ Rich law firms in Texas are getting richer.”

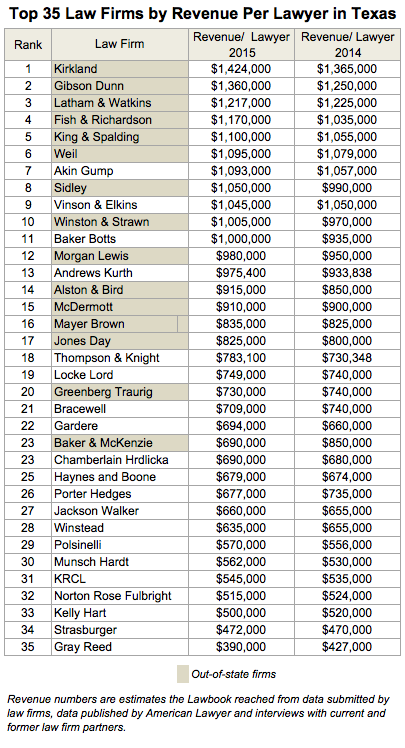

The Texas operations of 11 law firms generated revenues of $1 million per lawyer, a statistic widely viewed by the legal industry as a symbol of elite success.

Three of the 11 of the law firms are based in Texas. Baker Botts and Vinson & Elkins are headquartered in Houston. Akin Gump claims Dallas and Washington, DC as its primary residences.

The 11 elite firms generated $1.7 billion in revenues in 2015, according to The Texas Lawbook data. By comparison, in 2008, there were only two law firms – Houston-based Susman Godfrey and New York-based Weil, Gotshal & Manges – that reported $1 million of revenue per lawyer and only four other Texas firms that recorded revenues of $800,000 per attorney.

Two firms – Houston-based Andrews Kurth and Philadelphia-based Morgan, Lewis & Bockius – fell just shy of the $1 million mark last year.

“The wealthy, elite law firms have the money to hire away the best lawyers,” Walters said. “The best lawyers have the best clients. The best clients pay the most money, which means the highest revenues. And then the cycle starts all over again.”

The Texas Lawbook survey confirms the trend. Financial data examining 35 large business law firms shows that:

-

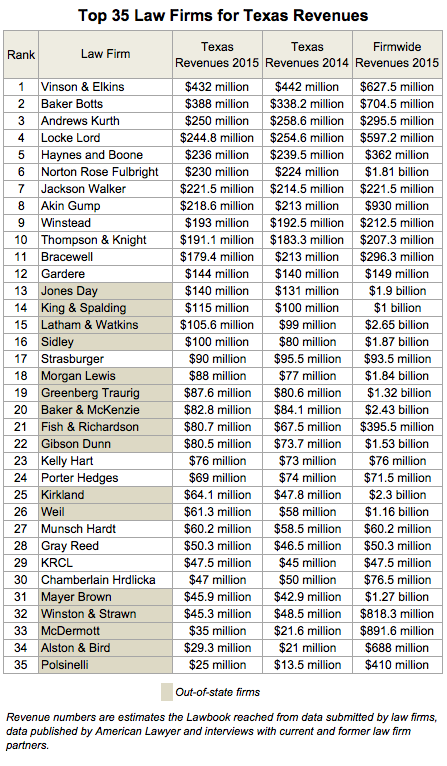

- The 35 largest corporate law firms operating in Texas generated $4.32 billion in revenues from their Texas operations in 2015 – up 2 percent from $4.22 billion in 2014;

-

- Sixteen of the 35 highest revenue-generating law firms operating in the state in 2015 are headquartered outside of Texas – up from 12 such firms in 2014 and four in 2008;

-

- Texas-based law firms generated $3.314 billion in revenues in 2015 – up from $3.309 billion in 2014, which is an increase of less than one-tenth of one percent.

-

- The Texas operations of the national law firms generated $1.005 billion in revenues last year – a 10 percent jump from the $909 million in 2014 and five times the $190 million in 2008;

-

- Seven law firms witnessed double-digit revenue increases in their Texas offices in 2015 – six are non-Texas firms;

-

- Kirkland’s $1.42 million in revenues per lawyer is double the rate of attorneys at Bracewell, Gardere, Haynes and Boone, Jackson Walker, Winstead and Norton Rose Fulbright.

The biggest shift has taken place in the corporate transactional area, where the elite law firms have nearly conquered the M&A practice.

More than half of the 25 law firms that handle the most mergers, acquisitions and joint ventures in 2015 were non-Texas-based firms, according to data from Mergermarket and The Texas Lawbook’s Corporate Deal Tracker.

The market shift started in 2010 but intensified and was magnified in 2015, when oil prices plunged and mergers and acquisitions in the energy sector went from hot to cold overnight.

“There is no doubt that 2015 was a challenging year for most law firms, including ours,” said Rob Reedy, managing partner of Porter Hedges in Houston. “Mergers and acquisitions in the oil and gas sector went from a record high in 2014 to a near crawl last year. At the same time, the capital markets practice all but dried up.

“Fortunately, the first quarter of 2016 started off much stronger,” he said.

The overall demand for legal work by Texas businesses was “anemic” or essentially flat in 2015, according to Matt Anderson, senior vice president and regional analyst with the Private Banking Legal Specialty Group at Wells Fargo in Dallas.

“Several Texas firms saw legal demand decline – some as little as 0.5 percent and some as high as 10 percent,” Anderson said. “The legal industry in Texas is essentially treading water. The Dallas and Austin firms are faring better than the Houston firms.”

Because legal demand is flat, legal industry analysts say there are only two ways to increase revenues.

“You either need to raise the rates you charge clients or you hire partners with strong books of business away from competitors,” Anderson said. “As a result, the fight for good talent in Texas is fierce.”

Law firm leaders and industry observers say lateral movement by partners from law firm to law firm hit a record high in 2015. National law firms seeking to enter the Texas market often make multimillion-dollar compensation guarantees to prominent lawyers who have books of business that they could bring with them to the new firm.

“This shift happened in other parts of the country a couple decades ago, but skipped over Texas because the state’s legal market was considered insulated from outside intruders,” said John Wilmouth, a senior adviser with Citi’s private banking law firm group.

As a result, national law firms found the Texas market closed because lawyers would not leave their hometown firms.

“Texas firms were historically hesitant to steal partners from each other,” said Jerry Clements, managing partner at Locke Lord. “But the lateral hiring frenzy has certainly hit Houston and Dallas now.”

What changed?

Many legal insiders point to a decision by corporate general counsel to stop hiring one or two large, full service legacy Texas law firms to do all their legal work.

Instead, prominent general counsel began preaching a new mantra: “We hire lawyers, not law firms.”

That seemingly innocuous decision by businesses unknowingly put into motion a series of actions that triggered the current law firm invasion.

In 2010, Latham & Watkins put the general counsel to the test by hiring seven prominent partners from Akin Gump, Baker Botts and Vinson & Elkins. Latham gambled that the corporate clients would practice what they preached and follow its outside lawyers to their new law firms.

As history – and lots of financial data – shows, it worked.

Latham’s office has been hugely successful. The firm now has 85 lawyers in Houston, reports revenues per lawyer of $1.2 million and surpassed $100 million in revenues last year.

Other national law firms quickly followed, as Texas lawyers who were once loyal for life to the law firm that recruited them in law school now readily jump from firm to firm for more money.

“A law firm’s number one asset is its lawyers,” said Richard Krumholz, a partner at Norton Rose Fulbright in Dallas. “Everyday, those lawyers walk out the door and everyday we have to work hard to make sure they come back to work in the morning.”

As the elite law firms conquer the premier clients in the high-dollar practice areas, such as capital markets, large M&A transactions, tax law and jumbo-sized bankruptcies, the rest of the corporate law firms fight to retain some business from long-time existing clients and seek new business in the upper-middle market space, according to Anderson and other legal industry analysts.

“There’s a lot of great legal work out there in the middle market and upper middle market,” said Gray Reed managing director Cary Gray. “Some of our best clients used to be clients of V&E or Baker Botts, but these clients found they could no longer afford these firms when their rates jumped from $700 to $950 an hour.”

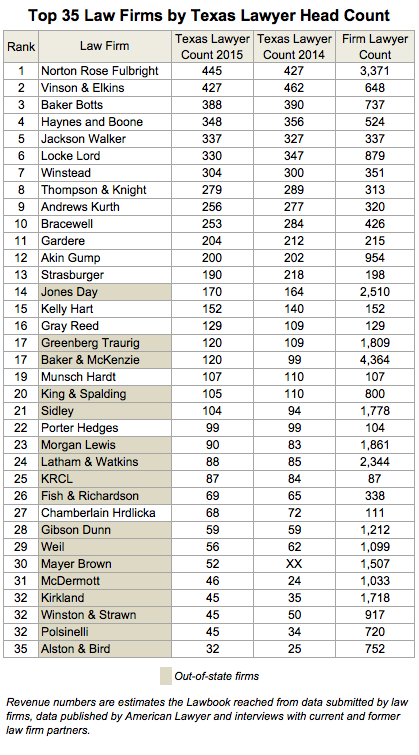

Six of the state’s oldest and largest law firms – Andrews Kurth, Bracewell and V&E in Houston and Haynes and Boone, Locke Lord and Strasburger & Price in Dallas – saw their revenues from their Texas offices decline in 2015 from one year earlier.

Three Texas firms – Winstead, Munsch Hardt and KRCL – report their revenues were up very slightly in 2015.

“Oil and gas M&A is down for every firm, but the bankruptcy and litigation practices have clearly picked up and the real estate sector is going gangbusters,” said Gardere chair Holly O’Neil, who added that 2016 has started much better than the same period one year ago.

One Houston energy law firm didn’t survive. Just 18 months ago, Burleson employed more than 110 lawyers and had revenues of nearly $100 million. They closed their doors in December.

“The biggest challenges for our firm are fluctuating commodity prices and increased competition,” Bracewell managing partner Greg Bopp said in an interview. “We need to stay focused on our core practice areas and not try to be all things to all clients.”

Bracewell has been hit hard, too. The Houston-based firm’s revenues in Texas sank 16 percent in 2015, as the firm saw its attorney count decline 11 percent and revenues per lawyer drop four percent.

Andrews Kurth and V&E were also hit hard by troubles in the oil patch. Both firms saw their strong capital markets practices sitting idle for the second half of 2015 and so far in 2016. Both shrunk their lawyer head count in Texas by 7 percent in 2015.

Not all Texas law firms suffered in 2015. Thompson & Knight increased its Texas revenues by 4 percent, while Jackson Walker and Gardere each grew its revenues by 3 percent.

“The volatility in the Texas legal market is something all firms have to confront,” Thompson & Knight managing partner Mark Sloan said in an interview earlier this year. “The economy is a challenge. Changing client demands is a challenge. Holding on to our talent is a huge challenge.

“We know we cannot get into a bidding war over talent with the wealthier firms,” Sloan said. “So, we must create an environment where lawyers want to work.”

No Texas-based law firm had a more prosperous year than Baker Botts. Total revenues for the firm’s Texas operations skyrocketed 15 percent – from $338.5 million in 2014 to $388 million in 2015.

Baker Botts also increased its revenues per lawyer to $1 million, which is 7 percent more than the year before and secured itself a spot as one of the elite law firms.

“We are witnessing a time when the practice and business of law is being challenged like never before,” said Andy Baker, manager partner of Houston-based Baker Botts. “Technology, higher client demands, law firm consolidation, new competitors and other challenges are making the business of law considerably more complex.

“Law firms either need to adapt or they will watch helplessly as their clients and their legal talent jump to other firms,” Baker said.

Analysts say that national law firms continue to open new outposts in Dallas and Houston.

“Despite the issues with oil and gas, many more national and global law firms still want to expand into Texas,” said Kent Zimmerman, a law firm analyst with Chicago-based Zeughauser Group. “Texas is much more than just energy. It is an extremely thriving economy.”

Law firms such as Alston & Bird, Greenberg Traurig, McDermott and Polsinelli have witnessed tremendous growth in Texas, even though few of their clients are oil and gas.

“Even if the energy or M&A in Texas becomes slow, we have structured our office with lawyers who are diverse in their practices and we think that makes our office here near-recession proof,” said Neil Wasserstrom, managing partner of the Texas operations of Mayer Brown, which is based in Chicago.

Zimmerman said he has “a number of law firms breathing down my neck because they want to move into Texas.” National firms want to experience the extraordinary success of those firms that have already opebned in Texas, he said.

For example, leaders at four elite mega-national law firms – Los Angeles-based Gibson Dunn and Latham & Watkins and Chicago-based Kirkland and Sidley Austin – report that their Texas offices are the most profitable in their entire firms.

“Truthfully, we braced for a slowdown in work last year, but we actually experienced a significant uptick in securities litigation involving shareholder lawsuits and a healthy increase in corporate transactional and bankruptcy work,” said Yvette Ostolaza, a partner at Sidley Austin, which now has offices in Dallas and Houston.

Sidley’s revenues from its Dallas and Houston offices jumped 25 percent in 2015 to $100 million.

“We are very bullish on Texas,” Ostolaza said. “I think you will see Sidley to continue to grow aggressively in Dallas and Houston during the next couple years.”

Editor’s note: The Texas Lawbook financial data is a combination of financial information provided by law firms, interviews with lawyers at the law firms and legal industry analysts who monitor firm financials and data reported by the American Lawyer. A handful of key law firms declined to provide financial data to The Texas Lawbook.