© 2012 The Texas Lawbook.

By Janet Elliott

Staff Writer for The Texas Lawbook

AUSTIN – Long known for its business-friendly litigation climate, Texas has quietly become the national leader in using the courthouse to punish one set of corporations, pharmaceutical companies that cheat government health programs.

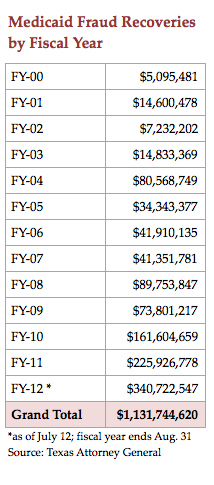

Teaming up with company insiders and others who claim to know of wrongdoing by suppliers to the Texas Medicaid program, the state over the last decade has recovered$1.2 billion from suits accusing drug manufacturers and health care providers of overpricing and fraud.

Records from the Texas Attorney General show that the $1 billion worth of recoveries resulted in Texas keeping $407 million, plus $92 million in fees for the AG’s office. The state sent $554 million to the federal government and $149 million to whistleblowers and their lawyers.

A recent analysis of all 50 states by Public Citizen found that Texas used whistleblower-initiated investigations more than any other state. In fact, Texas has become the role model for the rest of the country. By mid-July 2012, the federal government and the states had recovered a record $6.6 billion.

Texas’ program reflects an unlikely alliance between private trial lawyers and Attorney General Greg Abbott, a Republican who has regularly criticized lawyers who represent plaintiffs in lawsuits against businesses.

“The truth of the matter is, if Texas waited around for Uncle Sam to step up on the horse and ride up for the bad guys, they’d still be waiting,” said Patrick Burns, a spokesman for the pro-whistleblower group Taxpayers Against Fraud.

Burns also credits another Republican, then-Attorney General and now U.S. Senator John Cornyn, for taking advantage of whistleblower provisions Texas added to its law in 1997.

“I would like to say that salvation came from Washington,” he said. “I would like to say it came from Democrats. [But] it came from a Republican attorney general, it came out of Texas, Florida, the private bar and it came out of the West.”

The litigation not only has benefitted government coffers, but has been a boon to plaintiff lawyers at a time when medical malpractice and other traditional cases have slowed due to legislative limits.

“It’s one of the few areas that has been immune from the so-called tort reform movement,” said Tom Melsheimer, a Dallas lawyer who represented whistleblower Allen Jones in a lawsuit that alleged drug maker Johnson & Johnson falsely marketed its Risperdal antipsychotic. The case resulted in a $158 million mid-trial settlement in January, which is the largest Medicaid fraud recovery in Texas history.

The state’s recoveries have taken off since 2007, when Abbott requested money to hire additional lawyers after being questioned by legislative budget writers about 140 fraud cases that were languishing for lack of manpower.

Under the leadership of Raymond Winter, the Civil Medicaid Fraud Division has grown from nine lawyers to 33, and recoveries have leapt from $41 million in fiscal year 2007 to $411 million in fiscal year 2012.

Such numbers are inspiring other states. More than 28 now have whistleblower provisions similar to those in the Texas Medicaid Fraud Prevention Act. Even Congress has nodded its approval, allowing states with strong laws like Texas to keep a greater share of money recovered.

Cases Filed Under Seal

A case begins when a whistleblower files a lawsuit under seal and presents information to the AG. Abbott’s lawyers can initiate an investigation of the claims, using their authority to demand documents from potential defendants. If the state joins the lawsuit, it is unsealed. Any recoveries are divided among the federal and state governments and the whistleblower, who can collect 15 to 25 percent.

Defense lawyers criticize the law for allowing the state to keep cases under seal for years, during which time the defendant continues doing business with the state while the potential damages mount up.

All but two of more than 200 cases have settled before trial because the threat of trebled damages and penalties for each transaction “set the stage for pretty one-sided settlement negotiations,” said Joe Knight, managing partner of Baker Botts’ Austin office. Knight represented drug-maker Actavis in its appeal of the only Texas Medicaid fraud case to reach a jury verdict.

After a Travis County jury last year determined that Actavis should pay Texas and the federal government $170.3 million for fraudulent pricing of its generic drugs, the company sought a new trial, claiming that the Texas statute violates constitutional standards for fundamental fairness in civil actions.

In the three years before the case was unsealed, Actavis argued, not only did Texas officials not notify the company of its allegations, but the Legislature also increased the minimum penalty from $1,000 to $5,000 per violation and reduced the standard of proof for punitive damages.

“I do think there’s something wrong with a statute that would allow the state to continue doing business with somebody on terms the state has already concluded to be fraudulent without notifying the other party that the state has made that allegation,” said Knight.

The Actavis co-defendants dropped their appeal last December and settled for $84 million. AG spokesman Tom Kelley says the settlement was based on the ability of the defendants to pay.

From Key West to Austin

Texas’ effort actually began in 1999 when Austin lawyer Pat O’Connell went to work for Cornyn to head the new fraud unit. He reviewed several cases filed by the owners of a small pharmacy in Key West, Fla., alleging widespread overpricing of drugs sold to government programs.

O’Connell says the cases, which also were filed in federal court, had been languishing. He decided to intervene in 2000, making Texas the first state to intervene in whistleblower-initiated litigation targeting fraudulent drug price reporting.

The cases, known as the Ven-A-Care line, have generated $153 million for Texas out of an overall $498 million the AG and whistleblowers collected. Texas has recovered one-fourth of the $2 billion pharmaceutical companies have paid to all states combined and the federal government since the cases began.

In June 2005 testimony to U.S. Senate Finance Committee, O’Connell said that he didn’t initially plan to concentrate so heavily on drug manufacturers.

“The fact is that whistleblowers brought us cases which showed significant fraud in amounts which dwarfed the cases against other providers. Because of the limited number of staff and resources we can bring to any one case, we chose to pursue those cases which provided the greatest return to the Medicaid program,” he testified.

O’Connell left the AG’s office in 2007 and now represents whistleblowers.

Litigation to Continue

Although the Ven-A-Care cases are winding down, Abbott’s office says the upward trend of Medicaid fraud recoveries is expected to continue as more cases than ever are being filed for review. During the review process, it is critical for whistleblowers and their counsel to gain the attention of government lawyers.

“You’ve got to sell them on the merits of your case, which requires you to understand the facts and the law in a very detailed way,” says Melsheimer, who brought the Johnson & Johnson suit to the state. The AG’s office or Justice Department also wants to know what kind of resources the private lawyers bring to the table. The Fish & Richardson team led by Melsheimer in the Risperdal case, for example, helped manage 10 million pages of documents and 150 depositions.

“They told me flat out that one of the reasons they were willing to take this massive case was because I told them that we were going to put our best lawyers and our financial support behind the case,” said Melsheimer.

© 2012 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.