© 2015 The Texas Lawbook.

By Jeff Bounds

(April 11) – For Andrew Weiss and his employees at BSP Software LLC, it was time to celebrate.

The date was May 17, 2011. The occasion was BSP receiving patent No. 7,945,589 from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

For BSP and its sister business, Illinois-based BrightStar Partners, the patent was a victory over a former business partner, Dallas-based Motio Inc. The BSP-BrightStar business had once re-sold Motio software, but in 2009 had unveiled a competing product that their newly awarded intellectual property helped protect.

To commemorate the moment, Weiss circulated a photo of himself holding the ‘589 patent while wearing a t-shirt which read, “Muck Fotio,” court records say. He urged BSP employees to view the picture while singing “We Are the Champions,” court documents allege.

That picture embodies the animosity between the two businesses – animosity that today takes the form of a litigation war between them.

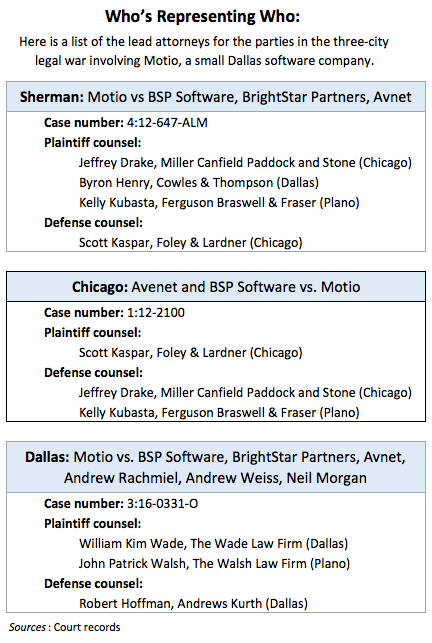

A dispute that began as a basic patent infringement complaint in Chicago four years ago has spread to federal courts in Sherman and Dallas, creating a threefold jurisdictional struggle that encompasses spicy allegations of patent fraud and the use of a fake identity.

In truth, the amount of money at stake isn’t huge. In fact, lawyer fees are likely to swallow up any cash awards that either side wins. When BSP-BrightStar sold to the Fortune 500 technology distributor Avnet in November 2012, it had annualized revenue of only $14 million.

But as is often the case where personal animus plays a role in litigation, the dollar sum at stake may not be the only factor behind the duration of the fight, outside lawyers say.

Motio scored some early victories in the struggle, including landing a $1.2 million judgment in Sherman in February on a patent infringement claim. Avnet on March 21 filed a motion asking U.S. District Judge Amos Mazzant to set aside the judgment.

“We believe the evidence supports our position,” an Avnet spokesman said.

Meanwhile, in Chicago, Motio has alleged that it has uncovered evidence that a pair of BSP officials obtained the ‘589 patent partly by submitting “doctored” evidence to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

In Dallas, Motio has charged that soon after unveiling their competing product, those same BSP officials fixed technical glitches in their offering by reverse-engineering Motio’s flagship software.

All defendants have denied wrongdoing.

But the court combat has taken a heavy toll on Motio, whose principal adversary in the case is now Phoenix’s Avnet, a Fortune 500 technology distributor that in 2012 acquired the BSP-BrightStar business.

Motio’s chief executive officer, J. Lynn Moore, has planned to offer expert testimony in Chicago that the business has lost sales of $1.9 million annually because the litigation has diverted him away from obtaining business, court records show.

Customer concerns about the court fight have also caused Motio lost sales, according to Moore’s planned testimony. The business has seen declines both in its total company revenue and in growth of its flagship software product, and has lost out on opportunities to be acquired, court records allege.

The magistrate judge overseeing the Chicago case, Sidney Schenkier, in March excluded most of the expert testimony from Moore that Motio had planned to introduce, although the Dallas company said in court filings that it may still offer his testimony as a fact witness.

Although the next trial among the three cases is set for Aug. 22 in Chicago, the dispute could be coming to a head sooner than that on several fronts.

In Chicago, Avnet on March 23 filed a motion for summary judgment on most elements of the case, including its claims that Motio infringed its two patents, Motio’s assertions that the two Avnet patents are invalid, and on Motio’s three antitrust claims.

The same day, Motio brought a summary judgment motion on its own contentions that it has not infringed the ‘589 patent and that the other Avnet patent is invalid.

In the Dallas case, Avnet has asked U.S. District Judge Reed O’Connor to toss out Motio’s suit, partly because, the defense maintains, Motio’s claims should have been brought as copyright infringement. Motio lacks a copyright registration on its software, the defense’s motion asserts.

Meanwhile, four outside lawyers not associated with the litigation said in interviews with the Texas Lawbook that they see significant hurdles that Motio will have to overcome to win its cases in both the Windy City and Dallas.

“It will be interesting to see how – or if – all the tentacles of this dispute come together in the end,” Carroll added. “This is the sort of scenario that often leads to compromise. But maybe not here. It’s been a long fight.”

Motio’s attorneys did not respond to a request for comment.

How it Began

Both Motio and BSP-BrightStar provide technology and services for what’s called “business intelligence software.”

Broadly speaking, this software helps turn a company’s raw data into forms, such as reports, that executives can use to understand how elements of the business are performing.

If, say, an executive wanted to see how a given product line was selling, business intelligence software could help create a report for that purpose.

For many years, a major player in business intelligence software was a Canadian business called Cognos. Starting in 2006, Motio began selling a product it had developed, dubbed MotioCI, which made improvements to Cognos’ offering.

The Motio product offers Cognos customers “automated version control,” or the ability to automatically keep different versions of content when various parties make changes to that content.

So if, hypothetically, an executive uses Cognos technology to create a report on a product line, the Motio product could keep different versions of that report in chronological order so the executive could track whom in her organization made what changes to the report as it circulated among managers and staff.

BrightStar, based in the Chicago suburb of Rolling Hills, is a technical services firm that, at one point, re-sold Motio products. That partnership came to an end on March 3, 2009, when BrightStar and its sister software-development business, BSP Software, released software to compete with MotioCI.

Today, Motio’s court filings say, that business and Avnet together control roughly 95 percent of the market for version control software.

Avnet’s summary judgment motion from March contends that both companies lack “any market power to control prices or output” among the roughly 23,000-plus customers that use software from Cognos, now owned by IBM.

“Doctored” Chat Logs in Chicago?

BrightStar fired the first legal volley, suing Motio in federal district court in Chicago in March 2012, a few months before its acquisition by Avnet. BrightStar claimed Motio had infringed two of its patents.

Motio returned the favor seven months later, claiming in federal district court in Sherman that BrightStar had infringed a Motio patent. Both businesses have denied wrongdoing.

It appeared that the dispute might come to an early end. Settlement negotiations between the two sides resulted in a term sheet getting on the table and a nine-month stay of the proceedings in Illinois in 2014.

But U.S. District Judge Joan Lefkow re-opened the Chicago case later that year, after Schenkier concluded that further talks would not help.

In early 2015, Judge Lefkow allowed Motio to add antitrust contentions to a counter-claim in which it had previously sought only to invalidate Avnet’s patents.

The reason: Motio claimed it had found out via discovery that Weiss and another BSP executive, Andy Rachmiel, had submitted a “doctored” chat log to the USPTO to try to help land the ‘589 patent that Avnet now accuses Motio of infringing.

Motio maintained in court filings that an analysis from a Chicago-area computer forensics expert it hired, Yaniv Schiff, showed that part of the chat log had been “altered,” another part “fabricated.” The men employed “emails using phantom names and alias email accounts” to hide the alleged subterfuge, Motio’s filings said.

Avnet countered with its own forensics expert, Jason Eaddy, who concluded that ready explanations existed for what Schiff had considered “inconsistencies” surrounding the chat logs, and that Schiff “did not account for them.”

In addition, Avnet contended that Motio had omitted “critical deposition testimony” from Weiss and Rachmiel that “readily explains” many points Motio made about the chat logs.

In a later order on a discovery dispute over privileged emails, Schenkier steered clear of ruling on the merits of Motio’s contentions.

“The question of whether (Weiss and Rachmiel) fabricated chat logs may hinge on a battle of experts,” Schenkier wrote in his order. “This complicated factual question is more appropriately determined by a trier of fact than on a discovery motion.”

Antitrust is Tough to Prove

Motio’s antitrust claims could provide it with something of a bludgeon in the Chicago case, simply because federal law provides for potentially big money verdicts, outside experts say.

“If Motio can provide its antitrust claims, it can recover treble damages, or three times its proven, actual damages,” along with attorneys fees, said Anthony Magee, a Dallas-based partner at Gruber Elrod Johansen Hail Shank who is not connected to the litigation.

In essence, Motio’s suit alleges that its opposition sued over a fraudulently obtained patent in the interest of forming a monopoly, court records say. Its suit also claims that Avnet entered into a conspiracy to restrain trade through its purchase of BSP-BrightStar.

The issue for Motio, experts say, will be proving it.

For one thing, when issuing the ‘589 patent application, the patent office did not rely on the chat logs that Motio claims were fabricated, court records say.

However, Judge Lefkow noted in a January 2015 opinion that if Weiss and Rachmiel indeed fabricated the chat logs, a court could consider that “affirmative egregious misconduct” – and, by extension, that would leave the patent unenforceable.

Motio faces a “significant hurdle” in proving that BSP engaged in fraud that played a significant role in the USPTO’s decision to issue the ‘589 patent, Magee said.

“Statements made to the patent office are often matters of interpretation,” he said. “Courts do not lightly hold that patents are unenforceable by reason of fraud.”

Ultimately, Motio’s antitrust case will hinge on whether the court decides the ‘589 patent is valid, Carroll said.

If the court upholds the ‘589 patent and Avnet wins on its infringement claim, “the basis for Motio’s antitrust claims disappears.”

Stolen Secrets in Dallas?

Motio could also face an uphill climb in Dallas, where it is alleging BrightStar officials tried to fix technical shortcomings in the first version of their software by reverse-engineering the MotioCI product, experts warn.

Less than a month after BrightStar announced its product in March 2009, Rachmiel got Motio to provide a download link to a free version of the Dallas company’s software by pretending to be “Cory Bradford,” a “business intelligence developer” in an Ohio office of the insurance giant State Farm, court papers allege.

Rachmiel forwarded the link to Weiss, who downloaded the software, installed it and examined it to understand how BrightStar “could use the code, source code and structure” to improve its own product, according to the Motio suit.

Originally filed in state court, the case in February was moved to federal court in Dallas.

By October 2009, BrightStar had unveiled a new version of its software, “improved to overcome much of its earlier technical difficulties,” the Motio suit contends. “In essence, BSP and BrightStar re-created Motio’s product by using the information they had unlawfully obtained.”

After Motio found out about the supposed issue in “other, unrelated litigation,” Rachmiel and Weiss continued “to actively conceal their wrongdoing” by “providing evasive and misleading information and testimony,” the suit says.

“To illustrate, Weiss denied that he ever obtained a copy of any version of the MotioCI software, when it turns out, that was a false statement,” the suit alleges.

Motio contends that the defendants are liable for various legal infractions, from theft of its trade secrets to fraud and civil conspiracy. It is seeking unspecified damages in excess of $1 million.

Was it a Trade Secret?

But Motio could face an uphill climb in proving parts of its case, outside lawyers say.

“Source code is typically considered a trade secret so long as the owner takes reasonable efforts to maintain its secrecy,” said Michael McCabe, a partner at Dallas-based Munck Wilson Mandala.

This means Motio could have trouble convincing a court that it took reasonable efforts to maintain the secrecy of the source code, he said.

“Motio opened its MotioCI webinar to the general public and permitted people to access the source code without a reciprocal promise from those same people (to) maintain the source code’s secrecy,” McCabe said. “The license agreement only prohibits the unauthorized use of the software. It doesn’t prohibit people with lawful access to the source code from disclosing or discussing it with third parties.”

However, McCabe noted, Motio can still sue for breach of its license agreement, assuming the defendants breached that pact in using the software or source code.

The ready access Motio provided to its software weakens a number of causes of action in its complaint, notably allegations that the defense breached the federal Stored Communications Act and the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, according to Shawn Tuma, a partner in the Frisco office of Scheef & Stone. (Motio’s court filings maintain that it did not make the source code for its software available to the outside world.)

Under the law, Tuma said, a loss in a civil claim is essentially the costs a plaintiff incurs in responding to unauthorized access to its computer systems, such as hiring computer forensics experts, time that employees spend dealing with the issue, or mitigation expenses.

“I would estimate that 80 percent of CFAA civil claims get dismissed for this reason,” he said. “The plaintiffs will read your article and clean (the complaint) up, if they can.”

Tuma believes Motio might have improved its chances by maintaining the defendants had broken the Texas Breach of Computer Security Law.

The reason: The law covers the knowing access of a computer network without the “effective consent” of the owner, he said.

“Consent is not effective if it is induced by deception,” he said. “That’s their best chance to win this case.”

© 2016 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.