Mikel Peter Eggert wasn’t a lawyer for very long, but he has proved to be a very persistent ex-lawyer.

And so’s his old man; but more on that later.

The First Court of Appeals on Tuesday rejected an appeal by Eggert to regain his license to resume a law career that was, by any standard, remarkably short.

Eggert graduated from law school at St. Mary’s University in 2002, earned a Pennsylvania bar card in 2003 and was licensed in Texas in 2004. By the end of 2005, his license was suspended, following his conviction— along with his father — for conspiring to fabricate evidence in an immigration case. He was formally disbarred in 2008.

Ten years later, having paid off his fine and served his probation, Eggert filed at the Williamson County courthouse in Georgetown for reinstatement of his license to practice in Texas. For reasons that become apparent in the telling, the State Bar of Texas resisted. And after hearing Eggert’s testimony in early 2019 — and that of his four character witnesses — State District Judge Betsy Figer Lambeth agreed: that the reinstatement of Eggert’s law license was not in the public interest.

Put simply, Judge Lambeth simply didn’t believe that Eggert understood the gravity of what he had been involved in; and it was that judgment that the Austin-based First Court of Appeals affirmed.

Eggert, who now runs a home irrigation repair business in Austin, says he may appeal; but he may not. “I still haven’t decided. I know I have a snowball’s chance in hell of winning.”

Needless to say, there’s deeper story behind Eggert’s quick exit from the profession.

Eggert’s problem stems from his involvement — along with his father, Peter Hellmuth Eggert — in an attempt to block the deportation of an Erath County man, Marcos Gallardo, who had pleaded guilty in 2002 to a charge of indecent exposure to a child. Though Gallardo, who was not a U.S. citizen, had originally been arrested in 1999 on a charge of aggravated sexual assault of a child, he received probation in exchange for his plea, apparently not realizing the conviction could result in his deportation.

In February 2003, Gallardo was arrested and detained by immigration authorities, and in November 2003, the Eggerts — Mikel and Peter —agreed to help him block his deportation. They proposed to do so, according to court records, by paying the child-victim and her mother to recant their accusations. And so they proceeded in that direction, the father and son, leaving in their wake a breathtaking trail of evidence and witnesses.

At the time Mikel Eggert was licensed in Pennsylvania but had yet to be licensed in Texas. In order to file paperwork in the case, Mikel recruited an Austin lawyer and former law school classmate to stand in for him. Though Mikel did the work, the Austin lawyer filed the papers. Sometimes, Mikel later admitted, he simply filed documents after forging his friend’s signature.

Meanwhile, the Eggerts approached the former police chief of Dublin, the Erath County town where the Gallardo incident took place. Lee Roy Gaitan, who was running for constable, had helped investigate the crime. In exchange for a proposed fundraiser, they asked him to approach the mother and daughter to ask them to recant their accusation. They gave Gaitan a check for $100, along with copies of the affidavits they were proposing for the mother and daughter to sign, along with instructions to get them notarized.

The officer later testified that he held on to the check and the affidavits, but that he did meet with the family. He told them they could talk to the Eggerts and that there “might be some money in it” if they helped Gallardo. The mother met with the Eggerts, took the affidavits with her to consider the proposal, then had her own lawyer deliver them to the Texas Rangers.

In June 2005, the father and son were convicted of conspiracy to fabricate evidence. Both were fined and sentenced to two years in prison but were placed on probation for five years. The State Bar of Texas suspended Mikel’s law license pending his appeals of his conviction.

And the father? The state bar found no need to pursue Peter Eggert’s law license because he never had one.

Born in Germany, Peter Eggert ran a commercial printing business and, with his wife, a drive-through beer store in Proctor, just a few miles southwest of Dublin, known as the Red Barn. Gallardo’s father had worked for him at the drive-through, which was the original connection to the younger Gallardo’s case.

Although the elder Eggert claimed to have had some legal training in Germany, Mikel says he is unaware exactly what that may have been. At one point, he said, his father had registered for an LLM program at his alma mater, St. Mary’s, but was turned down when the school couldn’t verify his German experience.

“Running a business, he had some experience with legal issues – but mostly through lawyers he hired,” Mikel said. “I think he really truly wanted to be a lawyer.”

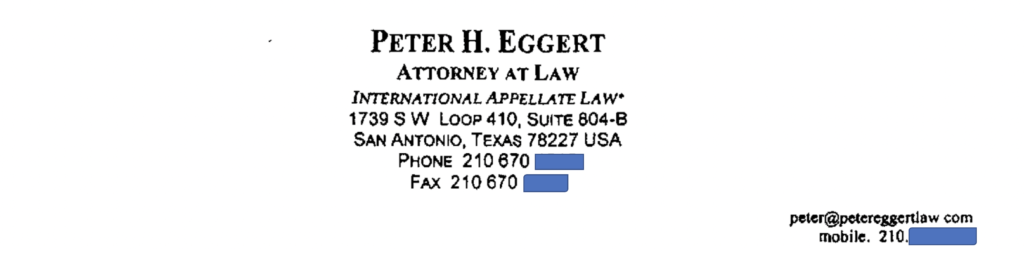

Even so, by the time they were in trouble, Peter Eggert had taken to presenting himself as a practicing lawyer, with stationery that referred to himself as an attorney and an email address linked to the website domain “petereggertlaw.com.” And following his conviction, as a condition of his probation, the elder Eggert was specifically forbidden from presenting himself as a lawyer or participating in any legal cases not his own.

In the years that followed their convictions, however, both father and son found plenty of work representing themselves. Mikel and father Peter filed multiple appeals of their conviction, appeals of Mikel’s suspension, writs of habeas corpus — all failed.

In 2007, the elder Eggert faced a bribery charge for his $100 check and promised fundraiser to Gaitan, the former police chief. He was convicted, but the resulting sentence was probated because he was allowed to declare that he had no previous convictions because his original case was still on appeal.

In the meantime, Peter litigated like a lawyer unchained. In his appeals he charged the jury with being tainted, the judge with being biased, his court-appointed defense lawyer with being incompetent and the district attorney with being corrupt. He sued Gaitan, the former police chief, for libel, charging that he had been an accomplice and, at one point, asked that the court force him to be examined for mental illness. He is listed as his own attorney on the docket of the U.S. Supreme Court where he attempted, again unsuccessfully, to get the court to grant certiorari for his habeas appeal.

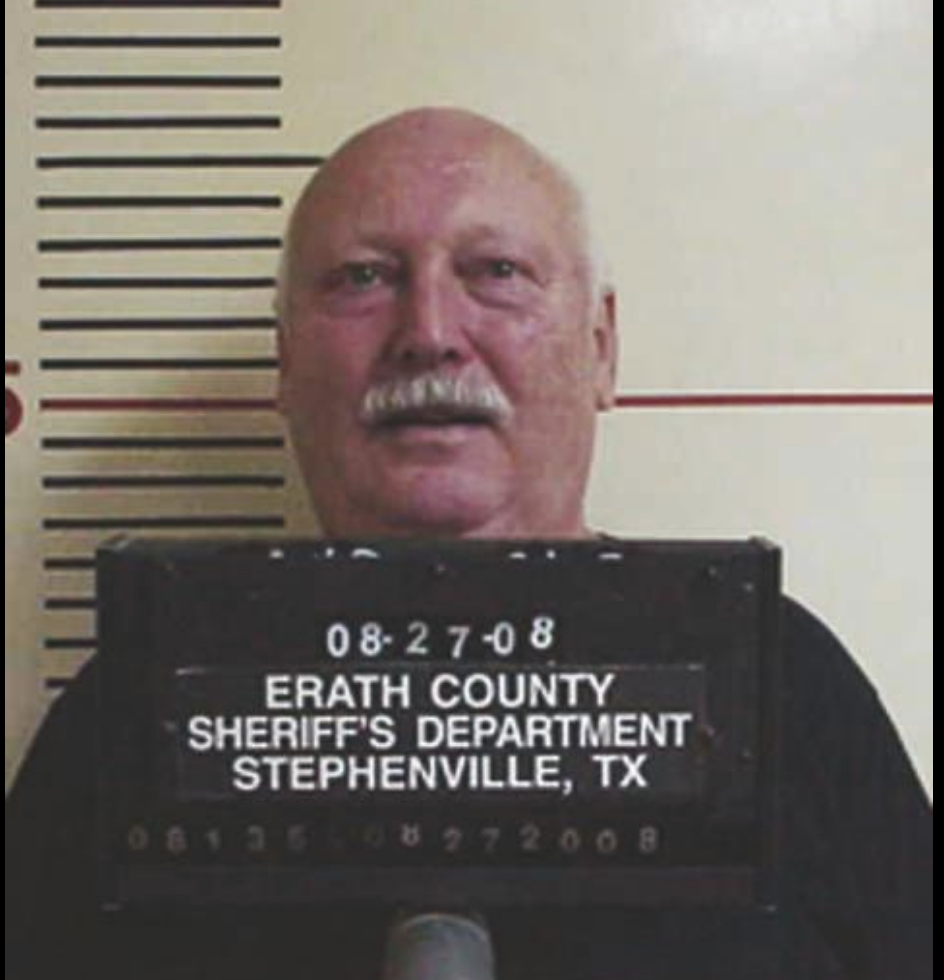

Peter Hellmuth Eggert circa 2008

In May 2010, Peter Eggert was back in court, this time facing a revocation of his earlier probation. He was charged with violating the specific terms of that probation prohibiting him from involving himself in legal proceedings. Eggert was accused of filing an adversary proceeding in a bankruptcy case before the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of Texas.

In March 2010 Eggert had filed the federal complaint on behalf of Maximillan LLC, a company created in Delaware that owned and operated the Red Barn drive-through beer store in Proctor. The managing partner was listed as Arlene C. Eggert, his wife.

In the complaint it was disclosed that Maximillan had given Peter H. Eggert “power-of-attorney” to handle the matter — a circumstance that might have been defensible. What proved indefensible was a letter dated December 27, 2007 in the appendix that accompanied the complaint. On the letterhead, was this:

Remarkably, when he was once again arrested by Texas Rangers, he presented them with a business card that read: “Peter H. Eggert, Attorney at Law.” And when the trial court decided that his actions in the bankruptcy proceeding constituted a violation of his probation, Eggert charged that the state court had “interfered in a federal court proceeding.”

According to Mikel, he has has been estranged from his father since the Gallardo incident. He says they haven’t talked in the last four years. And although 15 years have passed, he still struggles to find an answer for what he did that doesn’t lay nearly all the blame on his father. Time has filtered his narrative, which shifts on-a-dime from self-negating naiveté to self-excusing.

“Apparently, I’m not that smart. I’m just a dumb-ass loser,” he says at one point, ignoring the fact that he was 32 at the time and had passed the bar exam in two different states. But at another point, the mood shifts: “I had no intention of breaking the law. And then my father got involved.”

Thus, when he appeared before Judge Lambeth, he seemed unable to focus on the rock-hard sense of reality it takes for a lawyer to effectively protect the fate of others. Unable to rise above his own family history, his attitude toward what he’d done remained equivocal.

“I’m the first—the people that know me will tell you I’m the first to take blame for everything, it’s just kind of how it is,” he told the court. “But, yeah, if I had to sit up here and say he typed the affidavit, my father, he met with the witnesses, he roweled up the local attorneys.”

Asked why he didn’t stop his dad from breaking the law, he was even more tenuous.

“Who doesn’t trust their dad?” Eggert said.

Peter Eggert, who is now 74, lives in San Antonio. When contacted, he made it clear that the estrangement is not a figment of his son’s imagination.

“I don’t have a son,” said the elder Eggert. “And I wouldn’t lift a finger to help him. Is that clear enough for you?”

Asked if he was willing to discuss the circumstances of his own three convictions, he demurred. “I don’t have anything to say about that.”

The younger Eggert is now 46. He has a life he enjoys in Austin with a wife and a kid. Although he’s already thinking about his next opportunity to regain his law license in 2022, he wonders if that is the right decision.

“Whatever I decide to do, I have to weigh it against my life,” he mused.

He seems to truly believe that his unquestionable persistence will ultimately regain him his bar card.

“I don’t know who said it, maybe Babe Ruth. But it’s kind of hard to beat someone who doesn’t quit.”