Energy M&A has been shrinking of late — a hard notion to swallow when Exxon Mobil and Pioneer Resources just dropped a $60 billion deal at our doorstep.

Make no mistake, energy still reigns over Texas M&A, and has since 1901 when Capt. Anthony Lucas and Pattillo Higgins recruited a group of investors to help complete the Guffey Petroleum well at Spindletop. Whether by volume or value, Texas energy deals have consistently, but sometimes quietly, dominated the M&A landscape.

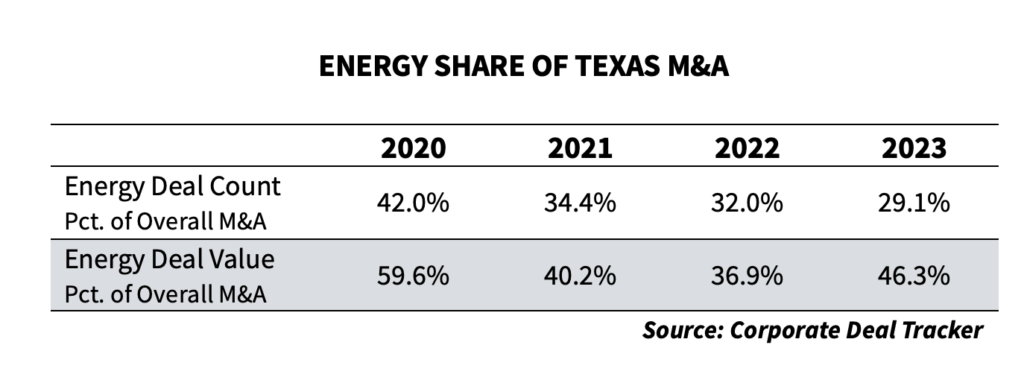

Since 2020, energy deals have comprised around a third of all reported Texas M&A deals, according to the Texas Lawbook‘s Corporate Deal Tracker. In terms of value, the share is even higher. Of nearly $1.5 trillion in 3,175 deals reported from the beginning of January 2020 through the end of September 2024, energy M&A deals accounted for $640 billion, nearly 43 percent.

But over that same 45-month period Texas-related energy transactions as a share of Texas M&A deal count has been in a slight but steady decline.

In 2020, energy transactions comprised 42 percent of all Texas-related M&A deals. That share dropped to 34.4 percent in 2021, 32 percent in 2022 and 31.6 percent in the first nine months of this year. Over those 45 months energy transactions accounted for 34.6 percent of 3,175 deals.

Viewed by value the picture is both different and the same. Energy deal values as a percentage of Texas M&A also declined in each year from 2020 through 2022. Over pandemic plagued 2020, energy represented 59.6 percent of all M&A by value in Texas. The energy share fell to 40.2 percent in 2021 and fell again in 2022 to 36.9 percent by value of all Texas M&A.

But in 2023, the market share of energy through the third quarter rose to 46.3 percent of aggregate M&A values in Texas — not including this week’s Exxon Mobil blockbuster.

Even though value — in one form or another — is at the heart of any M&A transaction, evaluating the market exclusively on value can be tricky. A single monster outlier can quickly distort a market. In the first half of 2012, for instance, energy provided 32.3 percent of the Texas M&A deal count and 84.7 percent of total value. In H1 2013, the energy share of the total Texas deal count was a nearly identical 32.1 percent, while energy’s market share of total value had dropped to only 33 percent.

So, what’s going on here?

Mike Blankenship, a partner at Winston & Strawn, says deals are down everywhere. Inflation anxieties and capital costs have created valuation problems, making firms reluctant to even put a finger on the trigger. A series of bank failures in March and April, for instance, resulted in closer looks at the valuations of deals across the tech sector, causing a ripple effect across deals already in motion.

But some of the problems are unique to energy. In particular, the politics of hydrocarbons have forced a reconfiguration of the sources of energy capital.

“A lot of the traditional financing in the sector has left, and there continues to be a high bid-ask spread on assets and companies,” said Blankenship. “Most companies are learning to be more disciplined with their expenditures.”

“The energy industry has a green problem and a red problem,” says Doug Fordyce, a partner at Lazard in Houston, in delightfully pithy agreement with Blankenship’s observation.

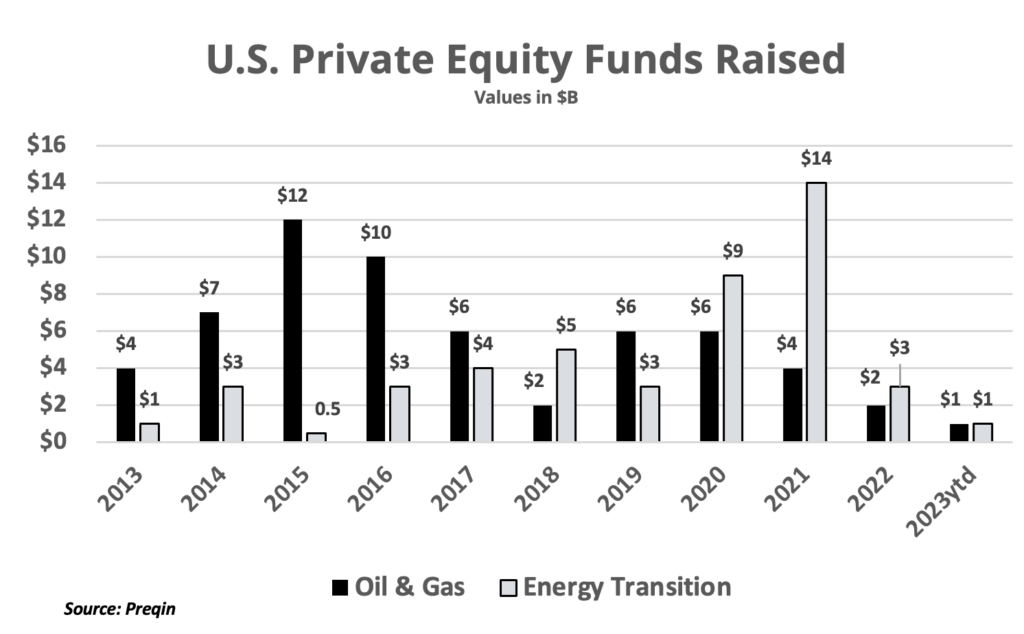

Speaking at the Mergers and Acquisitions Institute, Fordyce said traditional sources of energy capital have been in retreat for nearly a decade for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is that traditional investors — whether lured or bullied — have been paying more attention to energy transition than to energy sources themselves.

Institutional investors with long histories of traditional energy investments — retirement funds, university endowments and investment banks — have redirected capital because of ESG pressures. In December 2022, HSBC, one of the largest energy banks in the world, announced that it would stop funding E&P projects. Ditto global energy investor BNP Paribus, making good on its pledge of an 80 percent reduction in oil field financing by 2030.

Likewise major universities have axed their hydrocarbon portfolios. Some did so under ESG duress, Fordyce said. “They just aren’t willing to have students in their endowment offices protesting for 30 days.”

The capital retreat has had its effect. Since late 2014, energy stocks had underperformed against the S&P market, making them less attractive beyond hydrocarbon politics, even as oil production has regained the momentum it enjoyed before the pandemic struck.

According to the investment analysis firm Preqin, private capital has been retreating from traditional O&G for nearly a decade. In 2015, traditional energy funds $12 billion in capital. In 2022, that figure had dropped to $2 billion. On the flip side, private capital targeting energy transition, though miniscule in 2015, rose to $14 billion in 2021, driving a frenzy of investment following the pandemic years.

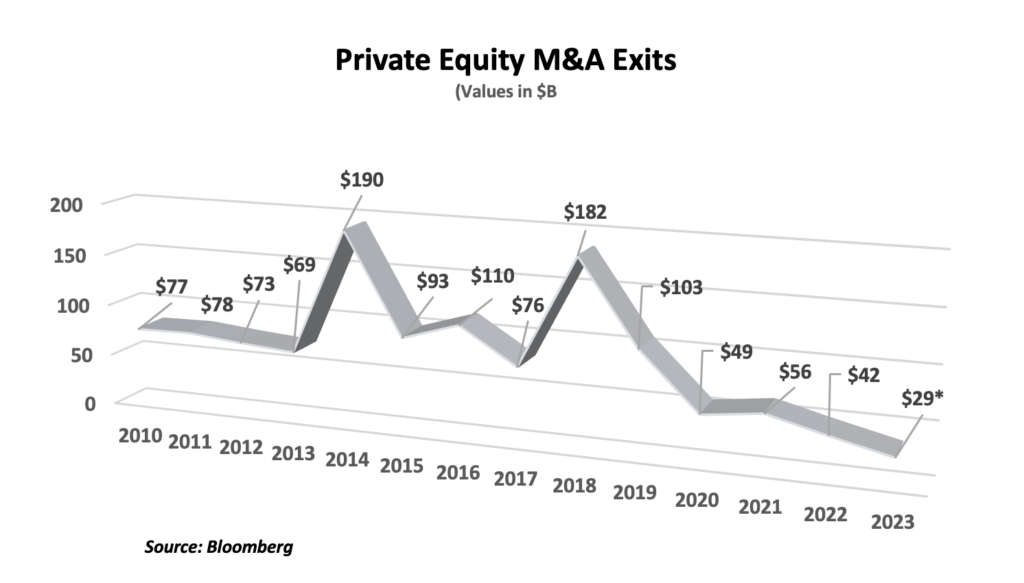

Likewise, private equity exits have faded. As recent as 2018, according to Bloomberg statistics, PE M&A transactions were valued at $182 billion. The combined value of PE energy exits for the three years of 2020-2022 was $147 billion.

“M&A follows capital formation and investment interest,” said Fordyce.

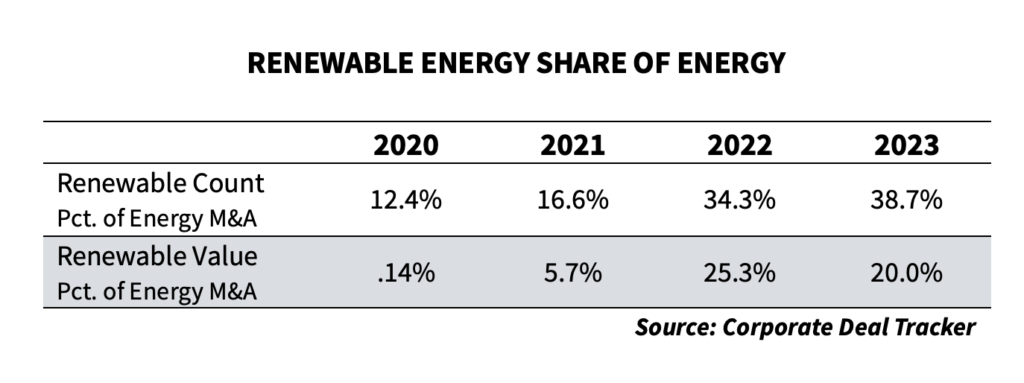

But energy is energy, whether fossil-fueled or renewable, and bolstered by that surge of capital energy transition deals have gained significant ground, even in traditional environments like Texas. In fact, as energy deals have declined as a percentage of Texas M&A overall, deals involving renewables and energy transition have increased dramatically as a percentage of energy M&A.

In 2020, the number energy transition deals comprised only 12.4 percent of energy M&A in Texas and less than 1 percent of value. In 2021 the renewable deal count ratio rose to 16.6 percent and 5.7 percent of value. In 2022, energy transition deals comprised more than a third (34.3 percent) of energy transactions and a quarter of value (25.3 percent). Through the third quarter of 2023, energy renewable/transition have been 38.7 percent of energy M&A transactions and 20 percent of their value.

Jessica Hammons, a partner at Akin, said energy companies have had to adjust their business behavior, a process that is beginning to pay off for those who did.

“Energy companies have had to live within their means.” By that she meant living with cash flow, holding more cash, showing more value to the public to attract investment, or even buying back shares when necessary.

“It’s been a matter of living with what you have and just being a good steward,” Hammons said.

Energy companies and the capital markets have responded by adapting their dealmaking in a variety of ways, by structuring deals with lower leverage, more cash, a more aggressive use of stock and a more prolific use of joint ventures.

The industry is also attracting new sources of capital, not only through joint ventures and novel equity arrangements, but through structured credit arrangements and securitizations and other arrangements that attract less expensive debt.

One increasingly important capital source, according to experts like Hammons and David Levinson of Pearl Energy Investments in Dallas, is the family office. Although there are downsides ranging from potential CFIUS obstacles to intra-family squabbles, family offices have money available for larger projects with longer exit timetables and reduced ESG concerns.

“With the retreat of traditional sources, alternative providers of equity — particularly family offices —are very interested in filling that void. Family offices that have come in are taking a bigger view and becoming a larger source of capital.”

These broad changes are having an effect, especially with the dawning recognition that the global dependence on fossil fuels can’t be eradicated by simply adding windmills to the nation’s power grid or switching to electric cars.

The stock market seems to have recognized that changing the fundamental dependence on hydrocarbons is going to take something more than the defunding of fossil fuels. The recent returns suggest that a mix of ESG initiatives within the industry and a more sober pacing of decarbonization has had an effect. According to an S&P analysis, energy was the highest performing sector during the third quarter of 2023, growing 11.3 percent while the S&P 500 fell 3.65 percent.

Alan Alexander, a partner at Vinson & Elkins whose practice includes energy transition, especially carbon capture and storage, says that zero-sum approaches to decarbonization are flailing in the face of fundamental consumer energy needs. He thinks a broader view of energy transition is necessary, one that includes a mix of decarbonized manufacturing processes, solar panels, wind generated power, carbon capture, electric vehicles — along with fossil fuels.

“Yes, nuclear (power) needs to be a part of that,” Alexander. The most promising decarbonization technologies, he says, are the technologies that are scalable. Electric vehicles require networks and commercial vehicles require greater battery storage for freight. Carbon capture requires large scale sequestration. And in Alexander’s view, the party best equipped to provide the necessary scalability for these projects is the energy industry itself.

“Working around the (energy) industry, one of the things that’s most impressed me is the broad base of technical knowledge and research among its technicians and engineers. They have the skills and resources not only to grasp the technical problems (of decarbonizations), but vision to provide scalable solutions,” said Alexander. “They just need to do what they do well: make sure that the lights go on when you turn on the switch.”