Imagine a law practice in which you serviced tens of thousands of real estate transactions annually and oversaw the litigation in thousands of cases a year.

Welcome to the world of Fannie Mae Deputy General Counsel Todd Barton and his team of 29 lawyers, paralegals and support staff.

Legal support for all properties in the U.S. that are acquired by Fannie Mae in foreclosure falls under Barton’s group, which is based in Plano.

Some years, that inventory has been at a measly 7,000 properties. Other years, it has been as high as 160,000. The result has been thousands and thousands of different pieces of litigation, which range from personal injury, property damage and even wrongful death cases. One dispute in New York lasted nine years. There have been multiple consumer class action lawsuits regarding the conduct of loan service providers.

Premium Subscribers: For a special Q&A with Fannie Mae Deputy General Counsel Todd Barton Click Here.

In the fall of 2019, Barton and his team were charged with representing Fannie Mae as a creditor in the Chapter 11 bankruptcy of Irving-based Ditech Financial, which involved the transfer of servicing of more than 428,000 mortgages with unpaid balances totaling $53 billion.

“The case was particularly challenging because it presented a novel issue of bankruptcy law regarding consumer claims, and the bankruptcy judge initially denied confirmation,” Barton said. “The goal is to manage the cases so that Fannie Mae suffers no financial losses and that any sales and transfers of servicing proceed smoothly with no adverse impact on borrowers.”

In the end, Fannie Mae was paid approximately $37.5 million under the confirmed plan, avoiding any financial loss.

Then Covid-19 struck, and tens of thousands of mortgage holders lost jobs, couldn’t make monthly payments and banks and lending institutions closed their offices.

How does Barton and his small band of in-house counsel handle such a massive caseload?

The answer to that question rests in the reason that the Association of Corporate Counsel’s DFW Chapter and The Texas Lawbook are awarding Barton with the 2020 DFW Outstanding Corporate Counsel Award for Legal Innovation.

“Todd showed remarkable resilience in 2020 as he led [his] team … through an unprecedented time in the company and country’s history,” said Fannie Mae Associate General Counsel Stephen Harris, who nominated Barton for the honor.

“When Covid-19 brought chaos to financial markets and uncertainty to millions of American homeowners and renters, Todd responded with a steady hand to help lead Fannie Mae in its efforts to bring stability to the mortgage market,” Harris said. “It is not an overstatement to say that Todd’s work in 2020 had a real, positive impact on our nation’s housing industry and the millions of individual borrowers who suffered from the pandemic.”

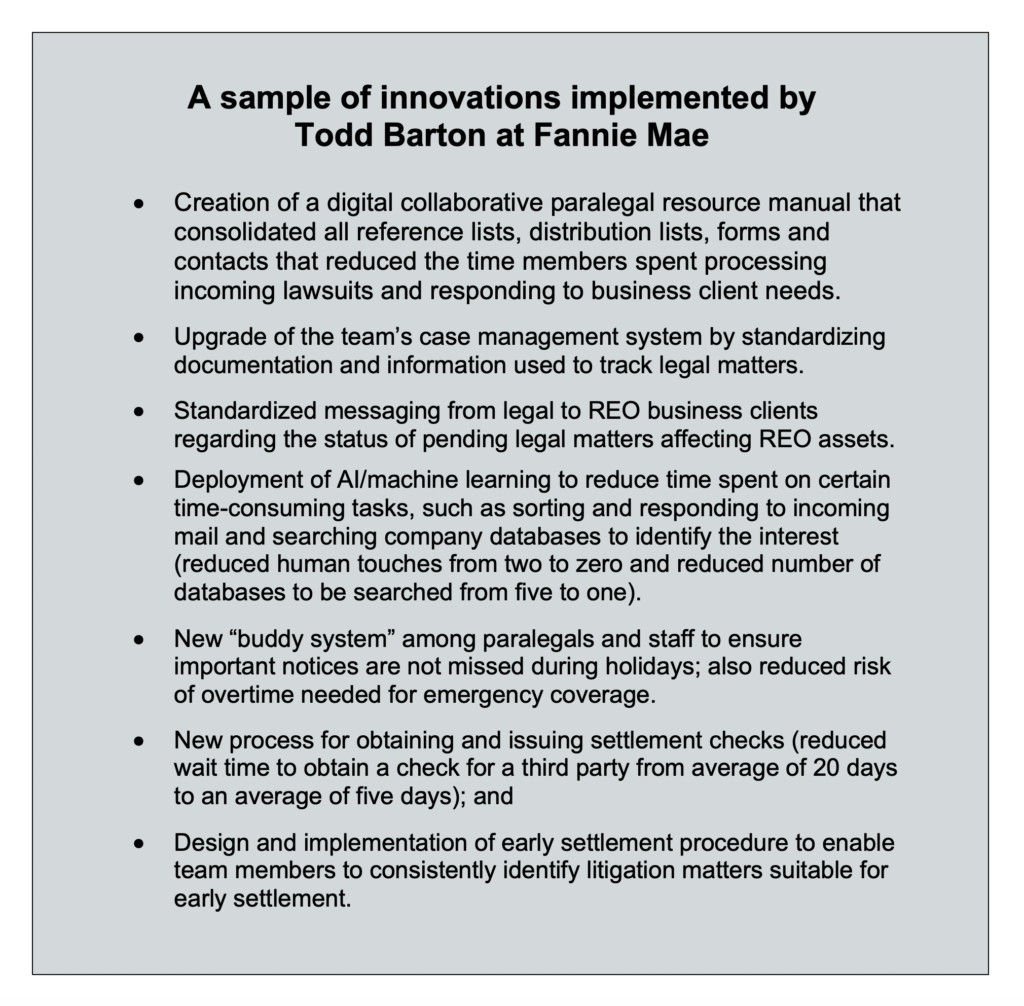

Harris said that Barton was encouraged by Fannie Mae executives to implement a formal lean management system, instituting new systematic problem-solving techniques that brought “efficiency, innovation and productivity” to the legal team.

The changes included upgrading the company’s case management system, deploying artificial intelligence, creating new processes for issuing settlement checks and designing new early settlement procedures.

Those who work with Barton say he is passionate about serving his client and the people around him.

“Todd pierces directly to the heart of an issue, approaches it from a pragmatic business approach,” said Wick Phillips partner Jason Rudd. “Todd provides specific and useful instructions for projections and follows up with clear feedback. Todd’s encouragement and positivity are infectious, and he sets the example of a caring, exceptional leader.”

Rudd and others said Barton’s loyalty to his team and his “brain power” are evident in his work.

“There are a lot of bright lawyers, [but] Todd makes the most of that native intelligence by working very hard,” said Carrington Coleman partner Ken Carroll. “You shouldn’t think you’ll outwork him. He’s extremely careful both in his legal analysis and in his approach to problem-solving overall.

“Todd will keep working until he finds a solution,” Carroll said. “I’ve known and worked with Todd since he was a very young lawyer. And those characteristics have always marked his practice. And he won’t ask more of you than he’ll ask of himself.”

Barton was born in Mooreland, Oklahoma, and grew up in the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles.

The law is in his DNA.

His father was a state court trial judge in Ellis County, Oklahoma, from 1967 until he retired in 1994. Before serving as judge, he served as county attorney.

Barton also had three uncles who practice law or served as prosecutors in Oklahoma.

“My uncle Sam was a colorful character,” he said. “His business card said that he ‘protected widows and orphans.’ He also had a sign in his law office with the Latin phrase that translated to: ‘Under the law for every wrong there is a remedy.’

“I admired my uncles growing up,” he said. “They always told great stories, and I thought they were cool.”

Barton said he thought about becoming a lawyer growing up.

“I cannot recall ever seriously considering anything else,” he said. “Having grown up around lawyers and farmers, if I was going into the family business, I was certain I was not cut out for farming.”

In college, Barton volunteered for Legal Aid of Western Oklahoma and had an internship with a prosecutor’s office. During law school at the University of Oklahoma, he did summer clerkships at McAfee & Taft in Oklahoma City. The following summer, he divided his time between a firm in Kansas City and Carrington, Coleman, Sloman & Blumenthal in Dallas.

“I got to watch now-U.S. Chief District Judge Barbara Lynn present an argument in a complicated matter in state court,” he said. “It seemed like every big firm in Dallas represented someone in the case, and a series of senior lawyers took turns at the podium. When it was Judge Lynn’s turn, I was blown away with the quality, organization and force of her presentation. I knew right then I wanted to work at Carrington Coleman.”

Todd (in bowtie) with his father Charley circa 1967

And he did. Barton graduated from the University of Oklahoma School of Law in 1989, and immediately joined Carrington Coleman. He made partner in 1996 and spent 14 years “working with and learning from some of the best lawyers anywhere.

“From the very beginning, I was given the opportunity to have meaningful roles on complex and interesting matters, including all types of bankruptcy cases, legal malpractice cases, director and officer liability cases and preference and fraudulent transfer cases,” he said. “I was very excited to become a partner at the firm, not because I expected to get rich, but because I had so much respect for that group of lawyers. If I was good enough to be one of their partners, that really meant something to me.”

Fannie Mae, which was created in 1938 during the Great Depression as part of the New Deal, was a Carrington Coleman client, and Barton represented the lender in several matters, including as part of a team that successfully defended a case involving the termination of a lender in Austin.

Fannie Mae Deputy GC Robin Gillespie, who was a former Carrington Coleman partner, told Barton in 2003 that one of her in-house counsel in Dallas was leaving, and she asked if he knew anyone who might be interested in the job.

Barton raised his hand.

“I loved my 14 years at Carrington Coleman and found my time there very rewarding,” he said. “But my two sons were ages 6 and 8 at the time, and I was working very long hours. With the large cases, it was feast or famine, and there was a lot of feasting. I made the difficult choice to leave Carrington Coleman for what I hoped would be equally interesting work but with a slightly slower pace.”

Barton quickly discovered that the lawyers in the Fannie Mae legal department had unparalleled expertise in mortgage law, including origination, regulatory, servicing and default, as well as litigation, corporate governance, tax, securities, employee benefits and human relations. His team provides legal support for Fannie Mae’s (1) credit loss management efforts, including foreclosures, bankruptcy cases, real estate owned (sales, closing, title and environmental), related loan-level or property-level litigation and mortgage default counsel; (2) document custody operations; (3) loan quality center; (4) consumer resource center; and (5) counterparty insolvency and bankruptcies.

FYI, Fannie Mae’s single-family business buys loans secured by one- to four-unit properties in the U.S. The company’s portfolio includes more than 17 million loans with an unpaid principal balance of over $3.2 trillion.

A major part of Barton’s job has been to manage Fannie Mae’s involvement as a creditor in bankruptcy cases involving the lenders who sold loans to the company.

Then came 2008 and one of the biggest challenges of Barton’s career: The Great Recession. When housing prices and values plunged in 2008, so did Fannie Mae’s stock price.

On Sept. 6, 2008, the Bush administration placed Fannie Mae and its sister lender Freddie Mac into the conservatorship of the Federal Housing Finance Agency. By February 2010, Fannie Mae had over 1 million loans that were 90 days or more delinquent, Barton said.

“Dealing with those loans through a variety of workout programs, nonperforming loan sales and foreclosure as a last resort was a tremendous challenge,” he said. “It took several years, but by early 2020 our percentage of seriously delinquent loans was back to where it was at the end of 2007.”

At the end of 2019, Fannie Mae executives adopted what it called a “new way of working” or WoW, which was based on Toyota’s lean management techniques that focus on driving efficiency and innovation by connecting daily routines to company goals, accelerating the ability to deliver value to customers, facilitating transparent and systematic problem-solving and enabling employees at every level to increase performance and work satisfaction.

The legal department was urged to participate, and Barton was assigned the task to lead it.

“Instead of resisting the change, Todd embraced it,” Harris said. “He saw opportunities for improvement of his team and team processes. He led the adoption of new types of meetings, new ways of analyzing issues, new ways to allocate resources and even a new vocabulary.”

Some of the techniques, Barton said, were simply an extension of something the team was already trying. Others were completely new and foreign.

“As with any new project or initiative, there were skeptics,” he said. “One of my roles was to get people to actively participate in the new activities and not to view them as simply the latest fad.

“My sales pitch was that innovation is absolutely necessary; to innovate you have to try new things; and that we would try the various techniques, use what worked and disregard the parts we did not find beneficial,” he said.

One newer innovation was the use of visual management techniques, such as “huddle boards,” which encourage teams of workers to collaborate on tasks jointly in order to see and understand the problem.

“There’s usually a problem and people automatically jump to solving the problem, which can result in an incomplete solution or unintended consequences.” he said. “But what is really needed is to step back to first figure out the roots of the problem and then figure out the solution.”

Barton spent the first three months implementing the new innovations, and then the Covid-19 pandemic hit, which presented a variety of new challenges, including remote working for the entire team.

“We had to figure out the logistics of all of that, including signing documents and accepting service of process,” he said. “There is also the challenge of keeping team members engaged as they deal with the pandemic and spending so much time at home.”

In response to the pandemic, Fannie Mae and its loan servicers implemented forbearance programs that helped more than 1.3 million borrowers with Fannie Mae loans. The company also provided lenders options to keep the mortgage market operating.

As a result, Fannie Mae provided $1.4 trillion in liquidity to the market in 2020, facilitating 1.5 million home purchases, 3.4 million single-family refinances and the financing of 792,000 units of multifamily housing – all as the pandemic raged on.

“Fortunately, our new ways of working were largely implemented prior to the onset of the pandemic,” he said. “We were able to continue conducting problem-solving sessions virtually to avoid a loss of momentum.”

Harris said that Barton’s leadership has been clearly on display during the pandemic.

“Todd led his team through managing the primary responsibility at Fannie Mae, a company that owns almost three of every five home loans in America, for interpreting the CARES Act in these areas and providing guidance to more than 1,000 mortgage servicers and hundreds of law firms throughout the country,” Harris said.

“Perhaps what is most amazing about Todd is that he did all of the above, and much more, with a smile on his face and an uplifting word for anyone who asked,” he said. “He focuses on what can be done, not on what can’t, and he always strives to do the right thing. His optimism and humor are infectious.”