It’s almost poetic: James A. Elkins married his bride in the shadow of Spindletop in 1904, just three years after the field’s legendary oil discovery that kick-started the Texas oil boom.

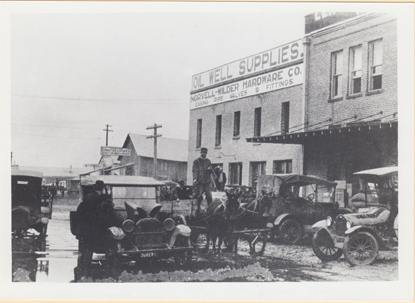

Though Isabel Mitchell’s Catholic parents were not thrilled about her marrying Elkins, a Baptist, a family friend offered his house for the wedding. It happened to be the former home of Captain Anthony F. Lucas, the Croatian-born oil explorer who in 1901 drilled a well one mile from his house that spewed oil like a volcano for nine straight days. The gusher attracted thousands of oil opportunists from far and wide to seek their own success in the sleepy town of Beaumont, population: 10,000.

Thirteen years after his nuptials, Elkins made his own imprint in the oil and gas industry when he co-founded Vinson & Elkins, one of the most reputable law firms in the world of energy.

But as V&E celebrates its 100th anniversary this year, its history shows that it is much more than a premier oil firm. V&E’s century-old namesake was around for – and in some instances, helped define – some of the most important history both inside and outside the legal world.

The firm has survived two World Wars, the Great Depression, a major client scandal that threatened V&E’s very existence and now an invasion by national law firms trying to poach the Texas firm’s top talent and clients. Lawyers at the firm have successfully argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, crafted deals for corporate clients that transformed the energy market and won multibillion-dollar verdicts.

“V&E has been a big contributor to the growth of this state,” said Pioneer Natural Resources Executive Vice President Mark Berg, who previously served as the energy company’s general counsel. “When you look at how Texas has grown over the years, not only with the energy industry, but other industries attracted to the state, having a quality law firm like [V&E] really played a key role in the enhancement of Texas over the last 100 years.”

V&E has championed improved legal services for poor, diversified Texas jury pools, humane prison conditions and affirmative action efforts in the state’s public universities. It was one of the first Houston businesses to offer same-sex employee benefits. The firm has long been a political powerhouse, as former partners include former Texas Governor John B. Connally, former Senate Majority leader Howard Baker, former U.S. Attorney General Alberto Gonzalez and former U.S. Trade Ambassador Ron Kirk.

With about 700 lawyers in 16 offices across the globe, V&E raked in $653 million in revenues last year. The firm’s profits per partner hit $1.8 million.

“Part of what I really enjoyed at V&E was the entrepreneurial environment and the opportunities they gave young lawyers to grow and learn,” said Berg, who began his legal career at V&E. “There’s a long history of its lawyers quite literally partnering with their clients.”

V&E teaches its lawyers not only “the judgment that goes along with being a good lawyer,” but also gives them “the opportunity to learn how to understand a business” and the way it operates, Berg added.

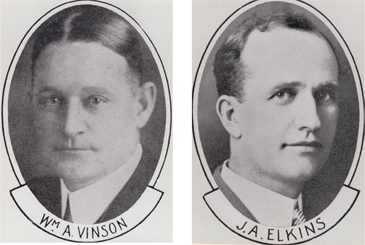

The story of V&E started a century ago with two small-town, entrepreneurial fellas.

‘How would you like to come to Houston?’

William A. Vinson and James A. Elkins were seated next to each other during a July 9, 1917 memorial service in the Harris County courthouse. Vinson’s partner, Ernest Wildbahn Townes, had died at age 42 after a long illness. Elkins had spent the past seven years commuting between Houston and his hometown of Huntsville.

Elkins longed to anchor his career in Houston after observing the success that others had enjoyed. He grew up next door to James Baker, founder of the 177-year-old firm now known as Baker Botts, although the women of the two families didn’t always get along.

In his history of V&E, Craftsmanship & Character, Harold M. Hyman writes that on one occasion, after arguing about “a long-forgotten matter… Elkins’ mother threw an un-plucked dead chicken over the fence at Mrs. Baker. “Neighbor Baker returned the fowl missile. Back and forth the little corpse flew until all its feathers fell out. Townsfolk were disappointed when the antagonists restored amity.”

Vinson, who grew up in Sherman, shared a small-town Texas background with Elkins, who was called “Judge” for the rest of his life after serving a two-year stint as county judge of Walker County. The two men chatted in front of the courthouse after the memorial service concluded. Vinson invited Elkins to his office in the Union National Bank Building.

Though he had “nothing in mind except to be courteous,” Vinson suddenly realized, “Here is your man,” according to V&E lawyers familiar with the story.

“How would you like to come to Houston?” Vinson asked Elkins.

“That is the ambition of my life. Make me a proposition,” replied Elkins, to which Vinson proposed a 60-40 income split to the end of the year and 50-50 thereafter. Elkins accepted.

“When can you come?” Vinson asked.

“I can come next week. I have nobody but my wife and [son] Bill and a few clothes I can put in suitcases and I am ready to move.”

They promptly formed Vinson & Elkins. The next month, they opened an office on the second floor of the original Gulf Building downtown. Early clients of the firm were primarily in the lumber, insurance and oil businesses. Early hires at the firm were primarily Huntsvillians, who played an important role in doing land and title work for lumber clients located primarily in Huntsville and other East Texas towns.

“There is no more important point or fact than the handshake decision of Judge Elkins and Mr. Vinson in the summer of 1917,” said Mike Harrington, a capital markets partner who edited Sidney S. McClendon III’s V&E: A Story of Vinson & Elkins L.L.P. “If that hadn’t happened, we wouldn’t be sitting here.”

V&E opened at a time when Houston was budding as a business-centric city. At the turn of the 20th century, Houston saw several events of profound significance. The discovery of Spindletop, as the McClendon book notes, “ushered in the era of oil and gas as the world’s principal source of energy.” The Great Storm, which devastated Galveston, shifted commercial and financial opportunities inland to Houston. Finally, the construction of the Houston Ship Channel made Houston a major inland port with direct access to the Gulf of Mexico and the world.

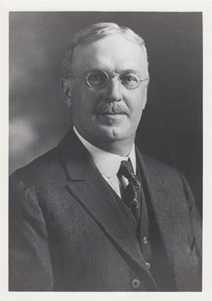

Each founding partner brought different contributions to V&E’s success. Vinson raised the firm’s profile in the early years, lobbying on behalf of corporate clients in Austin when the legislature sat and when state regulatory commissions met.

In 1940, Vinson tackled a pro bono case with a team of lawyers from the firm now known as Norton Rose Fulbright. The client was a poor, 18-year-old African-American convicted of rape. Vinson argued that the Harris County jury pool did not reflect the demographic make up of the community. Vinson showed that less than one percent of the people called to jury service in Houston were black, even though 20 percent of the local citizen population was African-American.

In a stunning landmark decision, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously agreed, ruling that jury pools should be “truly representative of the community.”

Judge Elkins focused on governing the firm and business development. Using his involvement in Houston’s prominent Suite 8F club at the Lamar Hotel and the bank he founded, Elkins brought prosperity to V&E. By the 1950s, Elkins led Houston’s largest law firm and oversaw the city’s largest bank, City National Bank.

The “8F Crowd” were successful businessmen that included Gus Wortham, who started American General Insurance Company with Elkins, and brothers George and Herman Brown, who founded Brown & Root. Both became V&E clients.

V&E scored its first large oil and gas client in 1921 when renown wildcatter Colonel A.E. Humphreys, who discovered the Mexia Oil Field, hired Elkins to sue Texas Company, which is now Texaco, for $1 million for unpaid oil purchases. Elkins resolved the issue in 40 minutes with a quick phone call to Texas Company’s general counsel, who was a close friend.

Humphreys immediately made Elkins his company’s lead outside counsel, which resulted in significant revenues for V&E for many years.

Other energy companies followed. By 1929, V&E had Vacuum Oil Company, Prairie Oil & Gas Company and Phillips Petroleum Company as powerful oil industry clients. At the same time, the large natural gas business Moody-Seagraves Company hired V&E to help it rapidly expand throughout the country.

The firm plunged into pipeline work in 1947, when the federal government decided to sell the Big Inch and Little Inch pipelines. Stretching from Texas to New Jersey, the government had constructed them during World War II as an alternative means for shipping crude oil across the country; too many oil tankers were falling prey to Axis submarines.

Elkins and fellow V&E lawyer Charlie Francis pulled together the investor group that formed Texas Eastern Transmission Corporation (TETCO), which today is a part of Spectra Energy. TETCO won the bid for the pipelines, paid $143 million, and, with the help of Brown & Root, converted the lines from crude to natural gas. Because the northeast was suffering from a shortage of natural gas at the time, the project ultimately transformed the energy market on the east coast.

Leadership After Elkins

V&E leaders say the hiring of David Searls in 1930 significantly impacted the future of the firm. As an associate, Searls successfully defended Pure Oil and other oil companies in antitrust litigation known as the Madison “hot oil” cases. In 1935, the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional Depression era price control regulations on petroleum products sold outside of production limits. When the nation’s major oil companies, in effect, continued the program without government approval, federal prosecutors indicted them.

Searls, who had been on a secondment assignment at Pure Oil, gained a new level of national respect for V&E when he minimized Pure Oil’s exposure in the sensational national case.

In the early 1960s, V&E under Searls’ leadership became significantly more aggressive in recruiting young legal talent, especially focusing on hiring top 10 graduates at the University of Texas School of Law.

“It really put V&E at the forefront of what became the modern recruiting wars,” said Jack Taurman, a litigator in V&E’s Washington, D.C. office and one of the firm’s historians. “We began recruiting talent from top law schools – not only from UT, but across the country.”

Searls also pushed for expedited promotion of young lawyers to partner, and exemplified a leadership style that got young associates involved in important decisions.

“Had we not done that, I think we all would have been left out in the cold in the 70s or 80s,” Harrington said.

One of the recruits from the class of 1963 was Harry Reasoner, who became Searls’ protégé, a nationally renowned trial lawyer and served as V&E’s managing partner in the 1990s.

In 1989, famed Houston torts king Joe Jamail hired Reasoner to handle the appeal of his record-setting $12.53 billion verdict for Pennzoil in its dispute with Texaco. Reasoner successfully kept $10.53 billion of the judgment intact. Two years later, Reasoner won a record-setting $1 billion antitrust award for ETSI Pipeline against Santa Fe Southern Pacific Corp.

Beyond big dollar corporate verdicts, Reasoner has also left a major imprint on V&E history through his public service work. In 1994, he defended the University of Texas law school’s use of affirmative action in Hopwood v. Texas before a federal court. He currently chairs the Texas Access to Justice Commission, a position he previously held in 2009.

While leading the firm, Reasoner also implemented programs to increase pro bono participation, launched the firm’s Women’s Initiative and began offering insurance benefits to same sex couples.

Enron: The Ultimate Hurdle

V&E faced numerous challenges during its 100-year existence. For example, nearly half the firm’s lawyers were drafted during World War II.

But no crisis compares to the Enron scandal, which started in 2001 and posed a true threat to the very existence of the law firm.

In the 1990s, the Enron Corp. had become the firm’s largest client, paying V&E more than $20 million a year in legal fees. When Enron’s fraudulent accounting practices were revealed, V&E and its role in the Enron scandal went under the microscope.

Many legal ethics experts say V&E’s biggest mistake came when it agreed to lead Enron’s internal investigation regarding allegations of accounting irregularities made by Enron vice president Sherron Watkins. Legal analysts say V&E should have referred the investigation to another law firm because V&E lawyers worked on some of the fraudulent deals in question.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, the U.S. Department of Justice and the federal bankruptcy trustee in the Enron liquidation investigated V&E. Plaintiffs lawyers representing Enron shareholders sued V&E as part of a huge securities class action lawsuit that sought hundreds of millions of dollars in damages from the law firm.

When Enron’s primary accounting firm, Arthur Anderson, was destroyed because of the scandal, many legal industry experts believed V&E would collapse, too.

Inside V&E, firm leaders feared its most valuable partners would flee to competitors and take their clients’ business with them.

“We testified in front of congressional committees; all of our lawyers were interrogated at length,” Reasoner said. “At the end of the day, we got a clean bill of health from all of them. Not one found that we had violated any laws or done anything wrong.”

After more than three years of investigations, the SEC and DOJ declined to bring charges against V&E. The lawyers representing Enron shareholders voluntarily dismissed V&E as a defendant. The firm survived with minimal defections by lawyers or clients.

Even so, the Enron scandal had a significant and negative impact on the law firm. V&E was aggressively trying to expand in Beijing and New York, but the Enron cloud made such growth efforts nearly impossible to attract lateral partners to the law firm.

“I think Enron – during the approximately five years that it [the scandal] existed – kept us from expanding and doing things,” Reasoner said. “But for me personally, I never understood why you would want to have 2,000 lawyers myself.”

“I suspect some of our best partners were offered opportunities to leave and go elsewhere,” Reasoner said. “And we lost maybe a handful, but very few.”

John Wander could have been one of those attorneys. He was promoted to partner the year Enron unfolded.

“I had lot of opportunities to go someplace else,” said Wander, who now serves as the managing partner of V&E’s Dallas office. “I was asked, ‘Why do you want to start your career as a partner at a place that’s going to die?’”

Wander said he stayed because he recognized the resilience in his colleagues, and admired the way they “put their arms around each other and faced outward.

“I took a look at the people around me and said, ‘These people are not going to let themselves get killed.’ We were very strong, and now it’s something that’s in the past. It makes me proud of how we lived through that as a challenge.”

The Modern V&E

V&E Chairman Mark Kelly points out that the firm is stronger today than ever before. Just about every legal ratings system recognizes V&E as the world’s leading energy law firm. V&E reported record revenues and profits in 2016. And the firm’s lawyers consistently rank at the top of all the M&A and securities offerings charts.

Between 2011 and 2016, V&E represented 388 Texas-based companies in mergers, acquisitions and joint ventures valued at $410 billion – 35 percent more than any other law firm, according to data from the independent research firm Mergermarket.

Even so, V&E faces increased challenges from changes in the Texas legal market.

Several major national law firms – Kirkland & Ellis, Latham & Watkins, Sidley, Simpson Thacher and Winston & Strawn – have opened offices in Houston and Dallas during the past six years and have hired away more than three-dozen V&E partners.

“Obviously, you lose some you wish you hadn’t lost,” Kelly said. “People leave for different reasons. Most of the lawyers that I think are driving the firm have stayed. I think that’s something I try to focus on every day to make sure they will stay despite the fact that all of them get calls every day.”

Kelly said a long-term goal of V&E is to become an elite top 25 law firm.

“We want to be viewed as an elite firm, not regional,” he said. “We want to grow and be bigger, but we want to do it in a way that makes sense to us. We are spending a lot of time looking at ways in which we can expand not only the footprint we have, but also doing things that are outside the energy space. I think it takes more work, collaboration and communication. We’ve spent a ton of time communicating with our lawyers that this is what we want to do.”

For example, Kelly said, the firm brought in 20 lateral hires, which helped deepen its bench in intellectual property. Last year, V&E opened its Richmond office, which focuses on strategic transactions that involve real estate investment trusts (REITs) and other specialty finance companies.

What would Judge Elkins think of V&E at 100 years?

“I think he would be very proud to see the firm today; the bank he built ultimately collapsed in the 80s,” Harrington said. “But the law firm that he and Mr. Vinson built together is still going strong.”