What happens when you have disgruntled workers, cheap-as-bottled-water fuel prices, a plaintiff-friendly area of the law and a raging pandemic that is bleeding companies dry?

Lots of law firms lining their pockets through the efforts of their labor and employment practice groups, of course.

New data provided exclusively to The Texas Lawbook by Androvett Legal Media shows that lawsuits tied to the Fair Labor Standards Act are heating up again after an already-toasty past several years.

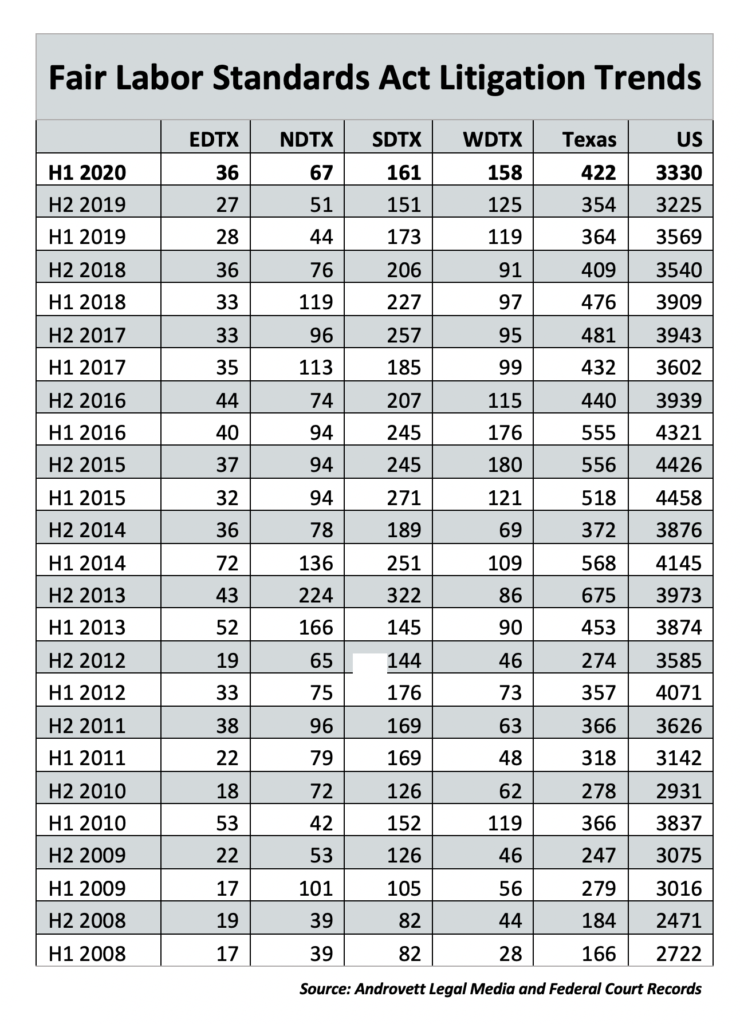

According to the data, there were 422 FLSA lawsuits filed across Texas federal courts during the first half of 2020 — up 16% compared to the same time period last year and up 19% from the second half of 2019.

Employment law experts say they expect to be occupied with more and more FLSA lawsuits over the coming months as companies continue to lay off workers as a result of COVID-19’s economic fallout.

“The employment numbers are just disastrous now for the country, and we’ll have a lot of folks whose unemployment and other benefits are running out,” said Margaret Allen, a labor and employment partner in Sidley Austin’s Dallas office. “They’re going to be scrutinizing whether they were paid everything they think they were owed by their employers and seeking everything they think is worth [pursuing].”

The extra free time and financial uncertainty that the pandemic has created for laid off workers will cause more people to take a harder look at what they think they were entitled to from their employer than they would have if they were simply changing jobs, experts say.

“If they basically swing from an old trapeze to a new trapeze without any break in employment, oftentimes they will blow off claims they could otherwise make,” Dallas employment lawyer Rogge Dunn said. “If an employee is thrown off the trapeze by the old company and they start falling, they’re going to look for a safety net.”

Trouble in the oil patch

When it was first signed into law in 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act created the 40-hour work week and established a minimum wage. Today in Texas, FLSA lawsuits — also known as wage and hour litigation — are largely made up of claims that employers misclassified workers as contractors when they were really employees or claims that workers were labeled as exempt from overtime pay when they should be classified as nonexempt.

Historically, workers laid off in the energy industry have banded together as the dominating group that drives FLSA lawsuits in Texas — both due to the industry’s prevalence across the state and the industry’s tendencies when it comes to operating in the oil patch. Labor and employment experts say that still rings true in 2020.

As a volatile industry that is prone to cyclical layoffs and relies heavily on hourly workers and contractors, the oil patch is perfect breeding ground for FLSA litigation.

As numerous recent bankruptcy filings by energy companies note, the pandemic and the Saudi-Russian pricing war have further impaired what was already a struggling industry in Texas’ workforce.

The struggle became evident in the second half of 2015, the Androvett data shows. Wage and hour lawsuits skyrocketed in the second half of 2015 and the first half of 2016, which saw 556 and 555 FLSA lawsuits, respectively, as a result of layoffs that were the product of a crummy commodities environment that began in late 2014 when oil prices tanked as a result of an oversupply in the global market.

Because of the pandemic, the Houston Chronicle reported last week that between March and July, the oil and gas industry laid off 39,900 people in Texas — 14% of its workforce.

The most recent data reflects just how dominant a hold the oil and gas industry has on FLSA claims.

As usual, the Southern District of Texas kept its throne as the prevailing region for FLSA suits to land. The region, which includes the energy capital of Houston, saw 161 such lawsuits during the first half of the year. But the Western District was not far behind.

WDTX, which stretches from Austin to El Paso, saw 158 cases. And if the numbers continue in an upward direction, the Western District could dethrone the Southern District as the FLSA capital of the state for the first time since in the last 12 years, if not more. Combined, the Southern District and Western District accounted for 75% of all FLSA suits filed in Texas for H1 2020.

The experts interviewed for this story couldn’t pinpoint a definite factor for the Western District’s gradual ascendancy, but a possible explanation is that plaintiffs are beginning to sue more often in the regions where the work took place. The Western District includes the Eagle Ford Shale and Permian Basin — the latter of which was the nation’s hot spot for exploration and production activity before the novel coronavirus screeched operations to a halt.

“An off-the-cuff thought I have is that we’ve seen significant growth in the Western District in areas like Bexar, Travis and Williamson counties and further west,” said Houston labor and employment lawyer Ashish Mahendru of Mahendru PC. “With the development of those localities, the plaintiffs’ bar has found the right ground for employers violating the FLSA … [and is] developing more of its business model in those areas.”

Mahendru predicted that FLSA claims will only increase and that the current numbers are yet to reflect the sheer volume of layoffs occurring — and increased litigious behavior as a result.

“You have to give layoffs time to take effect, and you have to give the rounds of unemployment benefits time to play themselves out,” he said. “You have to give the plaintiffs’ bar time to troll or pick and find plaintiffs, and then once that dust effectively settles, you get a filing.”

Low barriers

FLSA lawsuits were already popular among the plaintiffs’ bar due to the low barrier to entry and lucrative nature, the experts say. Plaintiffs’ lawyers are easily able to get their lawsuits certified as collective actions because the requirements are far less stringent than traditional class actions that have Rule 23 hurdles. Due to the ease of obtaining class cert, it often makes cases settle quickly, leading to earlier paydays.

“You just have to show that people are similarly situated, and if you can show that — which is a very low bar — you can be in a place where you can get conditional certification of a collective class and notice sent out to all reported potential members,” Allen said.

Due to the ever-changing regulations, FLSA also is attractive to plaintiffs because it’s an area of the law in which employers screw up often and easily.

“The defense for employers is an extremely complex and intricate area of the law, with new regulations coming out on a regular basis,” Dunn said. “It’s really something that you’ve got to keep your guard up and be proactive in terms of reviewing regulations, policies and procedures.”

What’s more, oil and gas companies are more likely to get sued in FLSA cases because of recent case law, experts say.

In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Epic Systems Corp. v Lewis that arbitration provisions can be included in employment contracts with respect to collective action claims.

Because the oil and gas industry employs so much of its workforce through staffing companies that provide independent contractors, the ruling meant that for the first time the staffing companies — which have the direct employment relationship with the contractors — were able to include arbitration provisions in their employment agreements.

While the Epic Systems decision was overall an employer-friendly outcome, experts say plaintiffs have since pivoted their strategy as a result so that they can continue to file FLSA suits as collective actions.

“Instead of suing the actual employer (the staffing firm), [contractors] are now suing the oil and gas company they were providing services to,” said Jamila Brinson, a labor and employment partner in Jackson Walker’s Houston office. “They’re doing that to get around the arbitration agreement and collective action waivers that the employees agreed to with the staffing firms.”

Experts say another trend that may surface — which will require employers to be extra diligent — is overtime disputes tied to the remote workforce the pandemic has forced upon companies.

“Working from home is not the same as working in the office, and the way to compute hours becomes very complicated,” Mahendru said. “Is the employee actually going to clock in and out every time they start and stop [work]? Employers have to have more flexibility now with mass-teleworking, but they have to implement HR policies and software that’s going to basically track when an employee is and is not working.”

Dunn agreed.

“My advice to employers is when you have employees working remotely, you need to be on guard to make sure they’re paid appropriately and that they’re actually working when they say they are,” said Dunn, who represents both plaintiffs and employer defendants in wage and hour lawsuits.

What’s Dunn’s advice to his plaintiff clients?

“Contact the DOL, read their website, Google the law and know your rights,” he said.