Wallace B. Jefferson always had a simple response to the question he has been asked over and over. Did he ever think he would one day become the state’s first African American justice and chief justice of the Supreme Court of Texas?

No, he didn’t.

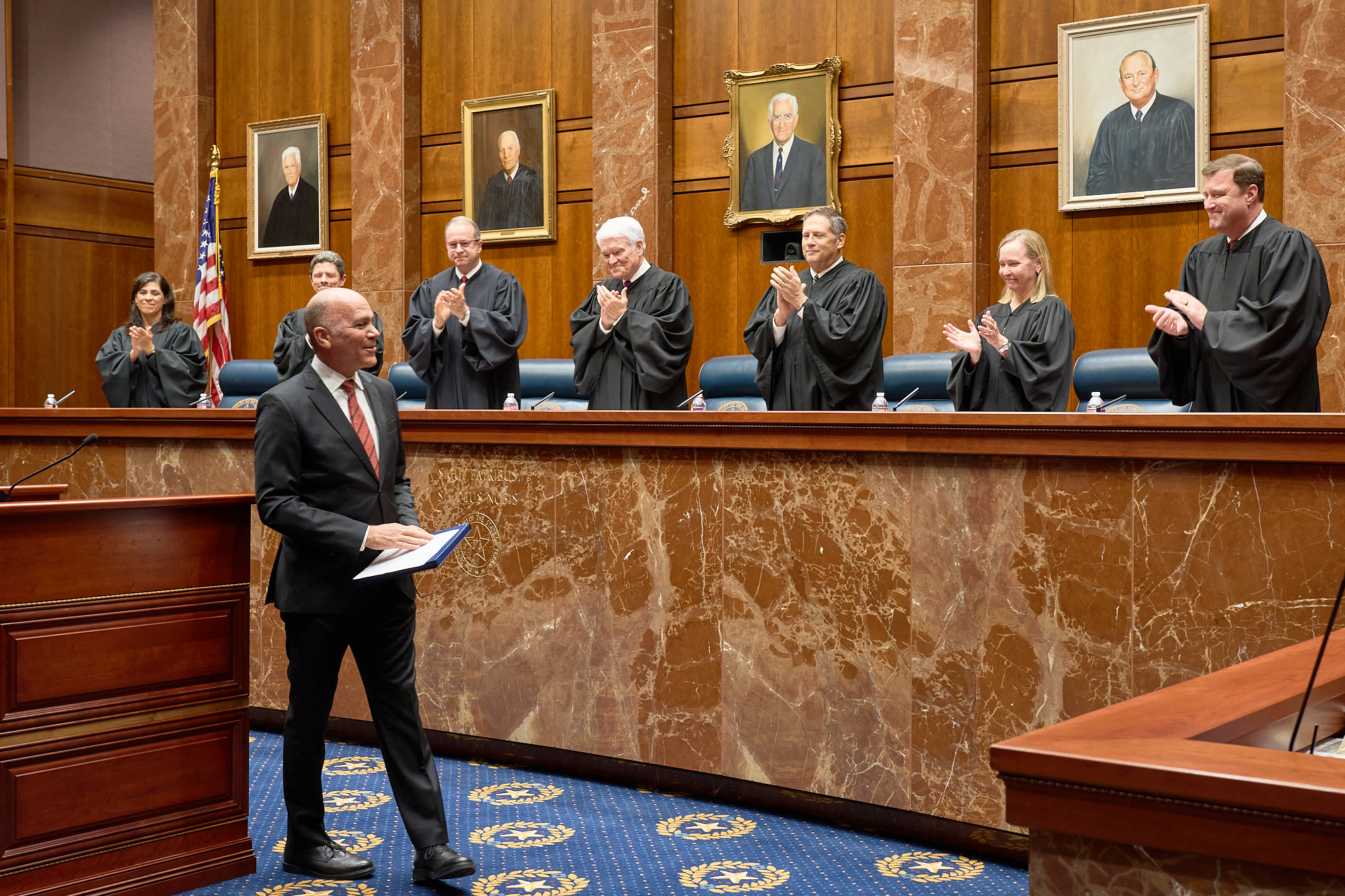

But as his legacy was celebrated Sept. 6 at a portrait unveiling ceremony in the red-marbled courtroom, Jefferson reflected on the course he could not have imagined 23 years ago when then-Gov. Rick Perry asked him to interview for a vacancy on the court.

He told the assembled crowd of well-wishers, including current and former justices and federal circuit judges, that maybe he had missed some signs.

Jefferson, 61, went to John Jay High School on San Antonio’s South Side, a school named after the Founding Father who served from 1789 to 1795 as the first chief justice of the United States. Jefferson studied at the James Madison College of Michigan State University, receiving a bachelor’s degree in philosophy.

When his brother Lamont Jefferson suggested the University of Texas School of Law, Wallace was one of nine students admitted to a coveted class taught by Charles Alan Wright, the premier constitutional scholar of his era. Each student played the role of a sitting U.S. Supreme Court justice deciding cases the court was hearing that term. Jefferson acted as Byron White.

Wright also prepared Jefferson for arguments when the U.S. Supreme Court granted his first petition for certiorari. “Justice O’Connor, the nation’s hero and my hero, wrote the opinion securing my client’s victory,” he said.

While the signs of a successful appellate practice were all there, Jefferson initially believed that none of his family had ever been a public official, let alone a judge.

“But there are caveats there, too,” he said. “My great-great-great grandfather, Shedrick Willis, was a public official. He served on the Waco City Council just a few years after the Civil War.

“And before that, he was private property, owned by Judge Nicholas W. Battle, a Texas district court judge.”

Jefferson was appointed to the court in 2001 and named chief justice by Perry in 2004. He won three elections before leaving the court in 2013. He is a partner at Alexander Dubose & Jefferson and a sought-after appellate advocate.

A big part of Jefferson’s legacy on the court came from his administrative duties, including statewide e-filing, the broadcasting of all oral arguments since March 2007 and an initiative to give youths a second chance by reducing municipal ticketing for juveniles, said Justice Brett Busby, who introduced Jefferson.

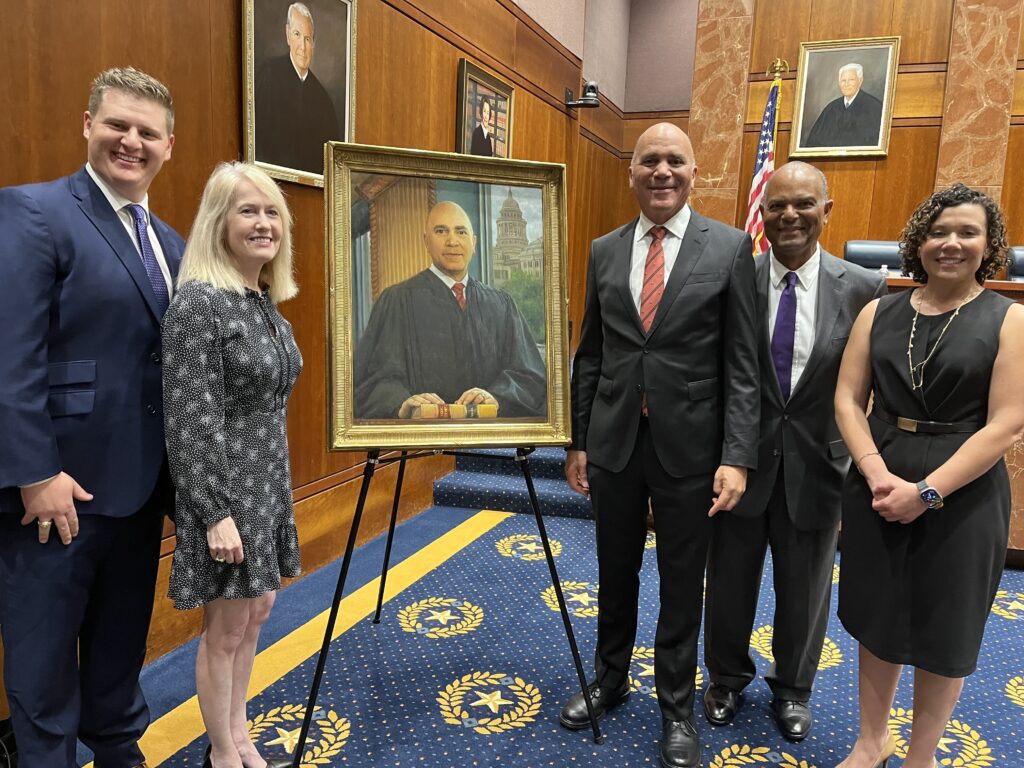

Jefferson credited his wife, University of Houston law professor Renee Knake Jefferson, with encouraging him to sit for the long-overdue portrait. He commissioned and donated the painting by artist Ying-He Liu, who has captured notables including groundbreaking U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Thurgood Marshall, Congressman Pete Sessions, the late U.S. Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnston and North Carolina Gov. Roy A. Cooper.

The portrait is different from many of those hanging behind the bench and along the courtroom walls and adjacent hallways. It depicts the judge, looking happy as he rests his hands on a lawbook with the Capitol dome visible through a window behind Jefferson.

The lawbook is Volume 24 of the Texas Reports, which contains a Supreme Court case affirming a decision in which Judge Battle declared that it was against public policy to enforce a contract to sell a free Black man into slavery, Jefferson said.

“And that was a remarkable and courageous ruling in 1856,” Jefferson continued. “After the war, that same judge not only enforced the newly amended Constitution but also encouraged those in power to trust his former slave as a leader in the community.

“Once master and servant, these two would become colleagues when Shedrick’s city council appointed Battle as Waco city attorney in 1870. Not five years after the war, these two men, now colleagues, guided the city into a new era.”

The book, a rare volume in nearly mint condition, was borrowed from Justice Evan A. Young. The tie worn by Jefferson in the portrait and at the ceremony is adorned with the logo for the American Law Institute, where Wright served as president for many years.

Although not in the portrait, Jefferson referenced Sam Houston’s Bible, which is often displayed when Texas officials take their oaths of office.

“Houston was a contemporary of Judge Battle and Shedrick Willis. An obituary noted that Shedrick, who was a blacksmith, shod Sam Houston’s horse,” Jefferson said. “Now get this. In a twist of fate, Houston’s great-great-great granddaughter, Marcy Greer, is my law partner today.”

Jefferson ended his speech by reading part of Longfellow’s poem, “The Village Blacksmith.”

Chief Justice Nathan Hecht said Jefferson’s portrait will be hung outside the courtroom because he is still a practicing lawyer with cases scheduled to be argued in the coming months before the Supreme Court.

Among those in attendance was retired San Antonio lawyer Tom Crofts, who started a law practice with Jefferson 33 years ago. Crofts, Callaway and Jefferson opened with no clients, books or office space but quickly became a go-to appellate boutique.

“I would like to be able to say that I can take some credit in his success, but the most important thing I can say is that even though he’s — I guess — 20 years younger than I am, he quickly surpassed me in all aspects of the work that we did very, very soon after we started working together,” said Crofts. “Eventually he was the father. I wanted to be like him.”

Also present was Sen. Judith Zaffirini, a public official with her share of firsts. The Laredo Democrat was the first Mexican American woman elected to the Texas Senate and in December 2023 became the first female dean of the Senate.

Zaffirini said she was not surprised that it took so long for Jefferson to sit for a portrait because she has long known him to be a modest person.

“But he did speak so meaningfully and so beautifully, and his message was superb,” she said. “His speech was perfect.”