It was the early 1970s and Mary Flood had abandoned her Michigan State journalism classes for a real newspaper job at the Lansing State Journal. She had stopped tying her brown hair back with her favorite green bandanna, a hippie look that once got her proudly kicked off the legislative floor.

When a state senator came under investigation over political contributions tied to the gambling bill he was carrying, she learned a way to beat the competition.

Follow the lawyers.

“I started writing about it, and I started driving to Grand Rapids, where the grand jury was, and sitting outside just like I did the Enron grand jury many years later. And they started playing music in the hallway because they were afraid I was learning something,” she said.

“But what I did was I followed the witnesses down to the parking lot and asked their lawyers what was going on. I knew the witnesses couldn’t tell me, but their lawyers could,” Flood said. “That was when I learned that the lawyers who are going to the grand jury or taking their clients in the grand jury are one of the best sources on the planet, which again fed me during Enron later.”

Over a 35-year career as an award-winning journalist, Flood would tail many a lawyer, landing scoops that exposed abuses by a charitable foundation, detailed the dominance of Houston’s most prolific traffic court lawyer and highlighted the work of a grand jury looking into Enron’s top leaders after the corporation’s spectacular implosion.

Mary Flood

Along the way, Flood changed her mind about the value of higher education and at age 40 obtained her law degree from Harvard. After practicing law in Washington, D.C., and Houston, she returned to journalism and built her legacy as that city’s best-known legal beat reporter for publications such as the Houston Chronicle, The Wall Street Journal and Houston Press.

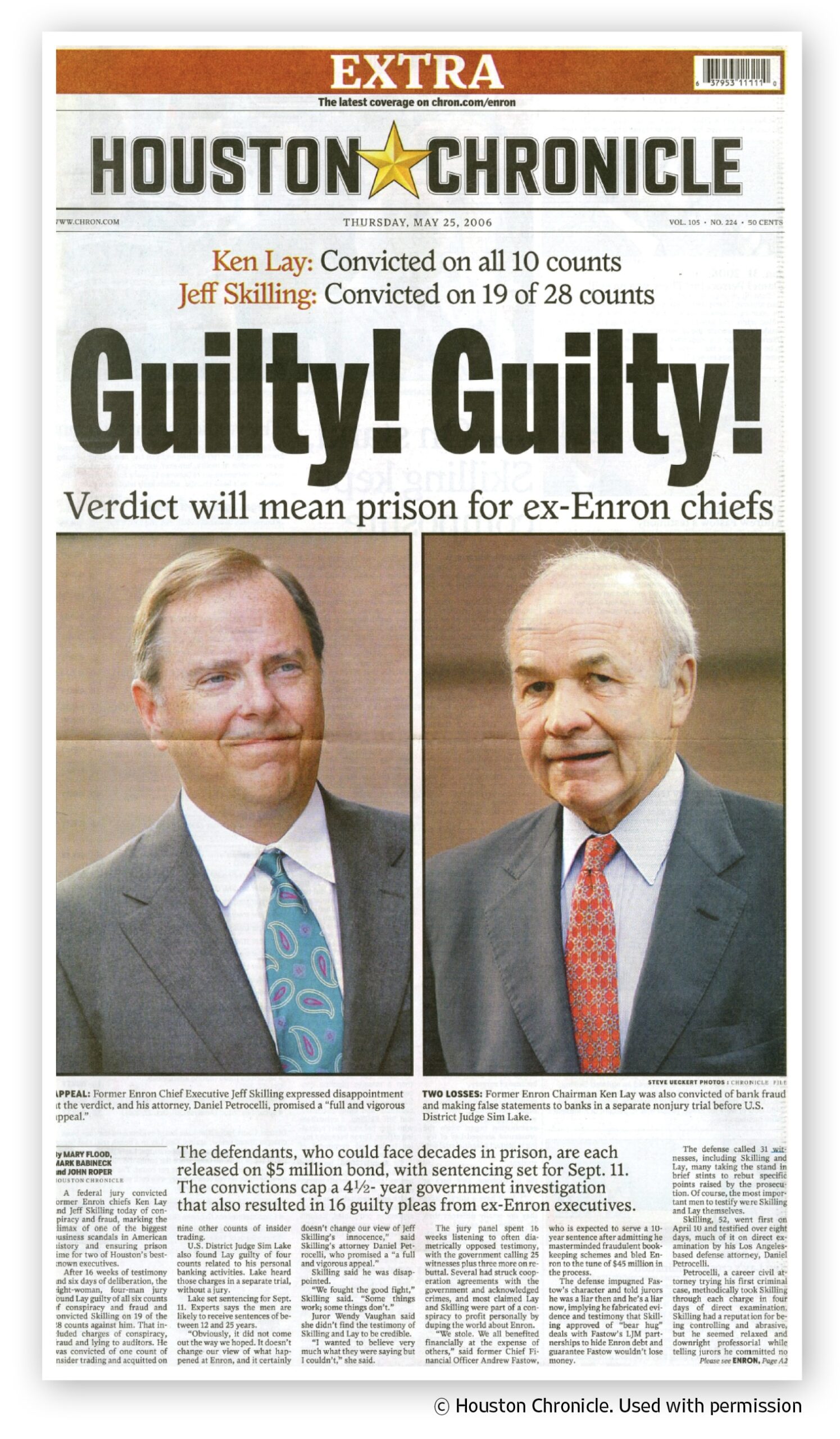

She would chronicle the downfalls of Bayou City top dogs Ken Lay, Jeff Skilling, John O’Quinn and Allen Stanford. Known for her love of a spirited conversation, she would bring together Houston legends Joe Jamail and Richard “Racehorse” Haynes for a storytelling session.

Her reporting went deep because her sources were vast. She made friends with judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys — but some of her most important sources were secretaries, court reporters and courthouse janitors. Regardless of political differences, she won respect for her diligence and ethics.

A lifelong Democrat who volunteered in 1972 for George McGovern, Flood’s diverse network includes judges and lawyers from across the political spectrum. When she left journalism in 2010 to become a media consultant for law firms, she remembers her going-away party was “a whole bunch of crazy-ass journalists, a bunch of federal judges.”

“Oh gosh, [Judge Edith] Jones was there from the Fifth Circuit. We’ve always gotten along, which is hilarious to anybody who knows us. But it’s because of a guy named John who I went to law school with and who clerked for her and introduced us in a way where we were able to find our humor, basically,” Flood said.

“But, you know, Edith Jones and me — not alike.”

Rusty Hardin first met Mary in the 1980s when he was a star prosecutor for Harris County District Attorney Johnny Holmes and she was covering the criminal courts beat for The Houston Post. When Hardin left the DA’s office for private practice, she wrote about his cases, including the federal prosecution of accounting firm Arthur Andersen resulting from Enron’s collapse.

“When you have somebody like Mary that’s impeccably honest, very intellectually honest, and is going to work hard to do the research and then write it well and quick, then you’ve got everything you can ask for in a representative of the Fourth Estate,” said Hardin.

When she became a consultant for law firms 14 years ago, he immediately hired her for her knowledge and deep love of the media.

“The media recognizes that authenticity, so it enhanced the services that she could offer a private client because the media itself knew that the client’s spokesperson was going to be impeccably honest with them,” he said.

For John Zavitsanos, Flood was the tough but fair reporter who knew all the judges and prominent lawyers in town and managed to earn respect from both plaintiff and defense attorneys with her coverage. He saw her as key to creating a unique marketing vision to help build his trial firm AZA.

“I thought, ‘Well, holy shit, I can have someone like Mary Flood, who is the dean of the Houston legal scene, be on our team,’ so I jumped at it,” said Zavitsanos.

Mary is my former colleague at both Houston newspapers, a mentor and close friend.

Like the best of us, her hair is now white. At age 70, she no longer stalks lawyers in parking lots. After reinventing herself as a rainmaker for Androvett Legal Media & Marketing, she has retired except for a few select law firm clients, including Hardin and AZA.

Flood is also a great subject for a Texas Lawbook profile. Information in this article draws from a four-decade friendship and interviews centered around a Houston Astros game last fall.

Flooding Down in Texas

As the ’70s gave way to the ’80s, Houston was booming and the Bayou City’s two daily newspapers were adding staff amid fierce competition. Flood followed two Michigan friends to the scrappier Post, starting as a general assignment reporter.

Her editors thought it was hilarious to send the aptly named reporter to some of the state’s many weather disasters. When a massive tornado caused death and destruction in Wichita Falls in April 1979, she called in her award-winning story from a sketchy bar in Oklahoma.

WICHITA FALLS – Doris King and her two daughters hunched down in their bathtub and repeatedly screamed The Lord’s Prayer at the top of their lungs Tuesday while a violent tornado devoured their house and spat it back at them.

Flood went to so many hurricanes that she started keeping two pairs of rubber boots in her trunk after a photographer took all her gear. At one scene, a man pointed a gun in her direction and shot a snake she had not seen swimming near her. He cut off the rattle and offered it to her.

“I didn’t know culturally that that was a nice thing to do, and I was just freaked out and I did not take the rattlesnake tail,” she said.

Mary Flood covered the aftermath of the deadly tornado that struck Wichita Falls as part of the Red River Valley Outbreak on April 10, 1979.

(Photo Courtesy of NOAA)

Her editors were right about one thing. It was a sure bet to dispatch Flood on breaking news.

“So, you walk up and say, ‘Hi, my name’s Mary Flood.’ You’re covering a natural disaster and your photographer’s named Jerry Click. And people start laughing, which is actually a nice entrée,” she said.

Back in the Post newsroom, reporter Rick Nelson began working to educate the young woman who grew up in a die-hard Yankees family about the merits of the local baseball team. Every day, he would quiz Flood and reporter Juan Palomo about Astros player statistics. After a week or more, they knew J.R. Richard’s ERA and Terry Puhl’s batting average.

“And Nelson just goes, ‘You are ready, my Astral children,’ which was wonderful. And the three of us had loge seats in the Dome together for years after that, which was really fun,” she said.

Nelson went on to write The Cop Who Wouldn’t Quit about a famous Houston murder case. Palomo and Flood still regularly attend Astros games, including one a while back where Flood had her picture taken with Puhl. She sent it to Nelson.

Criminal Courts, Hospital Scandal

Flood was learning the criminal courts beat as a backup for Gary Taylor when he was shot by a lawyer he was dating. Taylor would go on to chronicle his affair with the woman who was suspected of killing her husband in a 2008 book Luggage by Kroger: A True Crime Memoir.

At the time the tiny pressroom in the criminal courts building on San Jacinto Street was crowded with print, radio and TV newshounds. Flood thrived on the competition.

She talked up the judges and courthouse personnel. She let the daughter of one court coordinator join her daily rounds, a kindness that paid off later when the secretary called with a tip about bodies being dug up near Memorial Park. Mary got a copy of the search warrant and called to alert the city desk, which dispatched a police reporter and photographer to the scene. The next day’s Post broke the shocking story of serial killer Carl Eugene Watts.

With the Harris County DA’s office pursuing a record number of capital murder cases, the Post assigned reporter Mark Obbie to help.

“She spent a lot of time introducing me to her sources, basically ordering them to be nice to me,” said Obbie, now a freelance criminal justice reporter. “We’re talking about judges and DAs and defense attorneys. The judges — she would basically order them around. It was hilarious.”

When Obbie missed a story that the Chronicle had, Flood didn’t chew him out but took him in tow to grill the prosecutor who had failed to provide information. She pressured Obbie to start reading the sports pages so he could connect with the courtroom lawyers.

Obbie, who like Flood was from upstate New York, couldn’t fake his complete lack of interest in following sports.

“She said, ‘They know you’re a Yankee, this just makes it worse. You’re never going to go any place in this business if you can’t talk sports,’” said Obbie, who went on to top editor jobs at Texas Lawyer and The American Lawyer.

In January 1985, legendary broadcaster Marvin Zindler broke a story that people serving the Hermann Hospital Estate might be engaged in widespread corruption. Post investigative reporter Pete Brewton started receiving tips and asked editors to let Flood help him.

Walking along the beach in Galveston a few days later, Flood made the tough decision to leave the courthouse assignment she loved to become an investigative reporter. She and Brewton spent the next year breaking stories about how the hospital had strayed from its mission to provide charity health care.

“It was so exciting and interesting because we captured the imagination of the town,” Flood said. “Every day Pete and I would come in — this was before email — and get our mail, and it would be tips from people about things that had gone wrong.”

A tip that one executive was using funds intended for charity care to pay for his mistress’s condo led to a story about “condos, caviar and Cadillacs.”

The Post was killing the Chronicle, whose coverage was complicated because top editor Philip G. Warner was on the Hermann Hospital board. When the Post revealed that the Hermann estate had purchased a fleet of dirt bikes and jeeps for the use of Warner and other trustees on estate-owned ranch property, it was a juicy story. It also broke a relationship Flood treasured.

Joe Kegans, a pioneering lawyer who was the first woman district criminal court judge in Texas, had taken a liking to Flood and allowed her backdoor access to the courtroom. That access was important because Kegans sometimes locked her courtroom when child rape victims were on the witness stand.

But Kegans and Warner were drinking buddies, Flood said, and the next time their paths crossed, Kegans focused her steely gaze on Mary and proclaimed: “I have no use for you.”

“And I was really sad to have lost her respect for doing my job,” Flood said. “But I understand what she thought I should do: make an exception.”

The coverage won awards and led to change, including an increase in care for the poor at the hospital, at least for a while. People were indicted and went to prison. Jim Mattox, then Texas attorney general, settled a suit against the estate in exchange for additional charity care and board reforms.

The Post uncovered financial wrongdoing at other charitable trusts, including Methodist Hospital and the George Foundation, based in Fort Bend County.

In looking back at the saga in March 1986, Texas Monthly concluded that Houston’s elite “can no longer treat the city’s foundations like private playpens.”

Perfect Score

Working on the Hermann investigation started Flood thinking about becoming a lawyer and doing work like John Vasquez, an assistant AG who policed the foundations. The first step was completing a bachelor’s degree in general studies, which she did at the University of Houston’s downtown campus on a fast track while working full time.

In typical Flood fashion, she worked hard, earned good grades and made a perfect score on the LSAT. The University of Texas law school wanted her but so did Harvard.

“It was just too exciting an experience and too expensive to say no to,” she said. “But you know I went there with John Vasquez in mind and the AG’s office, which of course, when there weren’t Democrats running it, they haven’t done much of anything with that.”

One of her summer gigs was at Morrison Forrester, and after graduating cum laude in 1993 she worked in the firm’s Washington, D.C., media practice office for about a year. There were some fun assignments like helping on an amicus brief for National Lampoon in a copyright case over 2 Live Crew’s song “Pretty Woman.” The Supreme Court held that the commercial nature of a parody does not render it a presumptively unfair use of copyrighted material.

She also helped TV host Arsenio Hall get around the Fairness Doctrine so presidential candidate Bill Clinton could play the saxophone on air “without having every third-party candidate come on and play the kazoo.”

But Flood didn’t like the frequent transactional work where “we stayed up all night looking through, doing due diligence where you look at every single period,” and decided that a corporate law firm wasn’t going to be a long-term option.

Flood missed her many friends in Houston and moved back. She joined a plaintiff’s firm doing breast implant work until the practice was sold to John O’Quinn and she was let go. She hung out a shingle at an office across the street from Brennan’s restaurant and hoped to get court appointments from judges she knew.

A short time later a potential client came in to discuss being sexually harassed at a utility company. The woman had a good case, but Flood found herself warning about depositions and the belittling the woman likely would experience while being pressured to settle.

“It’s going to seem like you’ve been reused, and I need to warn you about what it’s like and what I’ve seen,” Flood told the woman.

“And she goes, ‘Mary, two things. One, I am thrilled you said that. That’s what I wanted you to say. My husband made me come here. Two, you might consider leaving the law.’”

Legal Shenanigans and Corporate Collapse

Flood called around to go back into journalism and was hired at the Houston Press, the city’s first free news and entertainment weekly.

She produced a 1997 cover story about O’Quinn’s DWI arrest with embarrassing details about police finding him with vomit-stained and unzipped pants, an empty vodka bottle in the seat beside him. O’Quinn was known for winning huge lawsuits against breast implant manufacturer Dow Corning but also was facing accusations of violating anti-solicitation rules.

Another cover article told the story of David Sprecher, the top defense lawyer at the municipal courthouse. Flood attended night court and saw person after person name Sprecher as their lawyer. After court adjourned, Sprecher headed to the parking lot only to find Flood’s imposing presence in front of his car.

“And he finally turned off his car and said, ‘OK, I’ll give you an interview,’” she said.

“The King of His Courts” ran in the late summer of 1996 and painted a picture of the scene.

In the corridor outside Court One, near the sign cautioning gentlemen to remove their hats before entering, a half-dozen strangers are huddled together, listening intently to the fast-talking guy with the trim gray beard who sits before them on a wooden bench.

“This city attorney is stupid,” he assures an elderly white woman. “She probably won’t even notice the defect in your complaint. What a meshuganeh pleading.”

The article caught the attention of The Wall Street Journal Houston bureau, which had been trying to get the Sprecher story. She joined the bureau in 1997 and covered the rise of lawyer advertising in Texas and business cases before the Texas Supreme Court.

In 2000 Chronicle Metro Editor Wendy Benjaminson hired Flood from the Journal to cover the legal beat.

“We needed someone who knew all the lawyers in town, knew what their strengths and weaknesses were, could jump in on court coverage,” said Benjaminson, now senior editor at Bloomberg News in Washington. “As you know, the law is one of Houston’s biggest industries, partly because it’s such a business center, partly because there is a lot of litigation in Texas and there is plenty of work for lawyers to get. And, again, Mary just had a terrific source network — every lawyer in town, civil and criminal.”

Flood first wrote about Enron through a tip about city government insiders getting stock in a new water company connected to Enron, then a fast-growing energy trading and utility company that had bought naming rights to the Astros new downtown stadium.

“I found out that Mayor Brown had some of the stock and that the wife of the guy at city hall who picked it worked at Enron,” she said.

A “pissed off” Lee P. Brown held a press conference to say that his stocks were in a blind trust but that he was getting rid of the holdings, she said.

Flood thought the Enron story was a one-off until 2001 when the company started to unravel in stunning fashion. Kenneth Lay stepped down as CEO and his replacement Jeffrey Skilling would resign six months later. Enron vice president Sherron Watkins blew the whistle on shady accounting practices, prompting the business to restate years of financial statements.

Late that year, Enron’s stock was reduced to junk status and the company filed for bankruptcy. TV news showed distraught workers carrying boxes from the downtown skyscraper distinguished by a large, tilted “E” out front.

Chronicle editors tapped Flood to lead coverage of a story that rocked Houston from the business and legal worlds to philanthropy, arts and professional sports.

“That was my next five years and the biggest story I’ve ever covered,” said Flood, noting that she met some of the nation’s top prosecutors and defense lawyers and became friends with some of them.

Once again, Flood decided to stake out the federal grand jury that was looking at charges against Lay and Skilling, among others.

Driving in to downtown from the west along Memorial Drive, she would look up to see if the lights were on in the eighth-floor office occupied by the Enron Task Force in the Bob Casey Federal Courthouse.

“I would call around to the best hotels in town that gave the government rate and ask for Andrew Weissmann or Leslie Caldwell,” federal prosecutors assigned to the task force, Flood said.

Waiting outside the grand jury for hours, Mary got to know people who worked in the building, including two female janitors who joined her on a hallway bench.

“They were like, ‘Who are you, what are you doing here?’ And we became really good friends. Whenever I saw them, they would tell me, ‘They’re here.’ I loved it,” she said.

Flood’s grand jury stakeouts were something not seen before by Weissmann, who supervised the prosecution of more than 30 individuals in connection with Enron.

“The way the grand jury was set up in Houston she could see who was coming in and out of the grand jury,” he said. “Not all courthouses are set up that way, but the Houston one was so she took advantage of it and that’s her right to do that.”

Her efforts to predict Lay’s indictment frustrated FBI agents and prosecutors, who at one point talked about subpoenaing Flood’s phone records to find out where leaks were coming from, according to an article published on the 15th anniversary of Lay’s July 8, 2004, arrest and indictment by retired FBI Assistant Special Agent in Charge Michael E. Anderson. The article also credited Flood’s reporting with disclosing new facts and witnesses that would benefit the FBI’s criminal investigation.

While frustrated by the leaks, Weissmann respected her legal knowledge and the two eventually grew close.

“Like at the FBI, agents who were lawyers were easy to deal with because they raised good questions and they also understand the common language,” said Weissmann, who served as the general counsel for the FBI from 2011 to 2013 and now teaches courses in national security and criminal procedure at NYU law school.

Flood credits her editors with giving her a long leash on Enron.

“I got to break a lot of stories again, partially because I knew what I was doing, I was smart about it, and partially because they let me take the time,” she said. “I couldn’t have done it if I didn’t have a job that let me do it.”

Tired of being beaten, some reporters began following her. Flood evaded male reporters by going into the women’s restroom and leaving by a different door. Other times she retreated to the chambers of a friendly magistrate judge.

The fraud trial of Lay and Skilling began on Jan. 30, 2006, and lasted four months. A typical day for Flood would begin when she got to the courthouse at 7 a.m. and end when she finished her articles around 8 or 9 p.m. Houston commuters would often hear her on NPR recapping the day’s testimony.

Carrie Johnson, who covered the trial for The Washington Post, said Mary “seemed to be everywhere all at once on the Enron story.”

“Once the trial kicked off, she occupied a central place in the courtroom. She sat in the same seat every day in that Ken Lay, Jeff Skilling trial. It was pretty marvelous to watch her work back in those days,” said Johnson, now NPR’s justice correspondent.

Interest in the trial was high, and the Chronicle assigned other reporters to blog about the testimony from an overflow room. On weekends, she would answer the many emailed questions that came in from readers.

Amid the daily grind, Flood remembers the fun stuff like the day the judge called all the lawyers to the bench. She watched as the male lawyers all turned to look at Enron prosecutor Kathryn “Kathy” Ruemmler, the sole woman in the group.

During the short recess that followed, none of the lawyers would tell Flood what was going on. A friendly court reporter, however, said that a juror had complained about a scent that was making her ill.

“They all thought it was Kathy’s perfume. Kathy wasn’t wearing perfume,” said Flood. “Dan Petrocelli, the lawyer for Skilling, was wearing this cologne that his wife got from Bergdorf’s that I by the way loved. He had to go basically scrub off this very expensive cologne because it was gagging a juror.”

Lunch with Legends

Flood said she first interviewed then-Judge Patrick Mizell when she was working on a story for The Wall Street Journal “about how stupid the bar polls were” and noted that Mizell was getting the highest ratings after being on the bench “like five minutes” because he came from Vinson & Elkins. A bit miffed at her initial tone, Mizell said, “We soon after became pretty good friends.”

Mizell occasionally invited her to have a drink with a group that included Joe Jamail and Harry Reasoner, lawyers she already knew from her years of covering their cases.

“They were pretty outrageous sessions. The stories they were telling, none of them were very politically correct,” said Mizell, who served on the bench for about seven years before returning to V&E. “Mary can hold her own with anyone, anywhere, and just do it through sheer sense of humor and wit.”

Flood got the idea in 2007 to bring Jamail together with Richard “Racehorse” Haynes for a conversation between Houston’s best-known civil and criminal trial lawyers, both octogenarians and actively practicing at the time.

“These guys are getting older, and they’re from the same years but completely different worlds. Wouldn’t it be fun to get them together,” she said.

“So, the criminal defense attorney Racehorse Haynes has incredible etiquette and is gentlemanly and amazing. And he was, you know, standing up if I stood up, and there’s Jamail swearing away. It was so wonderful, and they had respect for each other.”

Her account of the meeting was published on Sept. 9, 2007.

Though the two friends are family men, they also have the blessing and the curse of being defined by and addicted to their courtroom successes.

Neither Houstonian is particularly large in stature, yet both are bigger than life. For years now their presence in a courthouse, even on a minor matter, has attracted crowds.

Despite how their courtroom talents overlap, similar backgrounds and their 50-year friendship, there is a subtle undercurrent of competition, too.

When Jamail won the Pennzoil case, with its $400 million fee, he called Haynes and asked, “How many zeroes in a billion?” They had a drink and worked on the math.

Exhausted after Enron and getting job offers from other publications, Flood was asked by the Chronicle to recruit journalists and made several key hires. But as the 2000s were ending, newspapers were starting to shed experienced reporters in what would become an historic decline in newspaper publishing.

“They wanted to put me into management, and I would go to meetings where they would talk about reporters like they were fungible objects. I was horrified. And I’m not management material,” she said.

As fewer reporters were assigned to cover courts, Flood saw what she loved about how newspapers served their readers “just being eaten away like the ocean taking sand from the shore.”

From Reporter to Advisor

As a veteran reporter, Flood didn’t have a particularly high opinion of public relations work. She had appeared on panels with Richard Levick, a pioneer in crisis and litigation management, saying the appearances were like the debates on 60 Minutes between Shana Alexander and Jack Kilpatrick.

She accepted a job with Mike Androvett, a former TV journalist who founded a successful business helping lawyers promote their practices and deal with the media. Flood felt like she was jumping off a cliff when she took the job in the firm’s Houston office.

“What I didn’t know and Mike knew is that a whole bunch of people would call and ask me to work with them.”

“John Zavitsanos wanted to go to lunch with me the very first day I worked for Androvett and asked to hire me the very first day, which is pretty funny,” she said.

Zavitsanos said he was unhappy with the firm’s conventional marketing.

“We told her what our vision was. Make it unconventional, make it edgy,” he said.

She helped AZA develop an advertising persona to grow the firm “from about a dozen underrated lawyers into the much larger and well-known powerhouse trial boutique,” Flood said.

She’s had fun writing their witty ads and animations for more than 13 years, and stretched her skills brainstorming their holiday party invites, which has included a world-themed basketball and a snow globe with the Houston skyline.

“She still has a little bit of that cynicism like a good reporter should,” said Zavitsanos. “She acts as a sounding board for a lot of things that we want to do, a good many of which are stupid, and she will say it’s stupid.”

Flood recalls surprised looks on the faces of several television photographers when she first showed up at Hardin’s side during the criminal trial of a Harris County commissioner. She also fielded media inquiries as Hardin represented high-profile sports figures like Adrian Peterson and Deshaun Watson and astronaut Anne McClain.

As a reporter, Hardin said Flood had asked questions that were legitimate but that he didn’t always want to answer for tactical or other reasons.

“I don’t think anybody would have predicted that she would be able or willing to take that job in the private sector advising private clients about the media,” he said. “But [the media] got comfortable with the fact that she wasn’t going to shade it, they would trust her.”

She also worked with national law firms Sidley Austin and Winston & Strawn to help their Texas offices gain recognition and their lawyers’ expertise be featured in the press.

Androvett said hiring Flood was transformative for him and his firm.

“I’m a passionate guy and to find someone else who is as passionate about the work was so rewarding and reassuring, especially as I was trying to carve out and grow a presence in Houston,” he said. “When my kids were little, especially my youngest, Evan, she was so kind. She’d leave little gifts in the Houston office for them to find.”

Late in the 2023 regular season, Flood and I sat in Hardin’s premium seats at Minute Maid Park watching the Astros break a long homestand drought. She was enthusiastically cheering between sips of Diet Coke and keeping an eye on her phone for a text from an AZA lawyer about an imminent jury verdict. When the jury returned a sizeable award, she updated her pre-drafted news release and emailed it to several reporters in her contact list. They could call the winning lawyer, the release said, but were not to disturb Flood until after the game.

Humor Makes You Remember

Flood wears her sense of humor like the crown of a class clown. Being funny was highly valued in her family, and she loved to make her two brothers laugh. Her mother was an English teacher and vice principal at a struggling junior high school in Syracuse, and her father was a homebuilder and real estate appraiser.

Friends of Flood, numbering about 100, smile when they receive her personalized “cornball birthday whistles” each year.

Laughter spilled from her classroom when Flood was a top-rated adjunct professor of media law and ethics in the School of Communications at the University of Houston. But she was angry to discover student plagiarism and notes on the floor after a final.

When a new class started the next semester, she laid down the law.

“I remember starting the next class saying ‘My name is Mary Flood. Here’s the deal. There won’t be any cheating. I want to be clear. You’re going to get an F if you cheat this way, this way, this way. You’re going to get an F.’

“And three rows back, this guy goes, ‘Um, Professor Flood, will there be any cheating?’ And I remember thinking, ‘Oh, I’m going to fucking love you.’”

Flood’s humor is on display during her frequent appearances on the KUHF radio program, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, where she is the liberal voice dissecting local issues. During a recent taping, she referred to a cookoff associated with the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo as a “controlled drunken brawl” and said Blue Bell should introduce a listeria flavor ice cream instead of its new gooey butter cake offering.

‘Heartbreaking’ Judicial Sweeps

A longtime Democrat, Flood has despaired over recent partisan judicial elections that have swept out good judges because they were Republicans in blue Harris County. She saw the same thing happen to Democratic judges decades earlier.

“What I learned very quickly going to courthouses here is that the party means nothing when it comes to judging,” she said. “It has to be your intelligence and your fairness, and basically your character is what matters when you’re on the bench,” she said.

After the 2018 election, the Chronicle published her op-ed.

It is heartbreaking for those who know which judges are good, or even great, only to see them swept out of office by blind party voting. We lost many great jurists this election. Maybe their replacements will be great, too, but at least some of them won’t.

After this year’s March 5 primary, Flood told Houston Public Media that she was disappointed in the Democratic primary results, which saw three well-regarded incumbent male jurists defeated by female candidates. She was quoted saying that the system is “tragically flawed” when “ignorant voters just picked female names,” a trend which has resulted in some less-qualified judges presiding over Harris County courts.

When Mary was writing her legal blog for the Chronicle, she said a lawyer called to ask why she was publishing information about lawyer discipline that would appear in the Texas Bar Journal. She responded that most people don’t get the Bar Journal and “it’s not just lawyers who need to know who is disciplined.”

The current legal news scene has robust trade publications widely read by lawyers, but Flood believes much has been lost from the days when local newspapers and broadcasters vied for the best courthouse stories.

“I think it’s really dangerous because courts have so much control over people’s lives, family to criminal,” she said. “They control whether you get your kid and people don’t have any idea or have much less idea, except for lawyers.

“I think that the legal media itself telling lawyers what’s going on has broadened and gotten much better, especially Law 360 and this publication, Texas Lawbook. But I think that the general public is much more in the dark than they ever have been. And I’m really sad about it.”