© 2014 The Texas Lawbook.

EDITORS NOTE: The Texas Lawbook provided extensive coverage of the trial. For previous articles about the case, please scroll down.

By Natalie Posgate

Staff Writer for The Texas Lawbook

DALLAS (March 4) – A Dallas jury, in a potential landmark verdict, ruled Tuesday that two businesses can be involved in a legally binding partnership even when one of the parties never intended for the joint venture to be official.

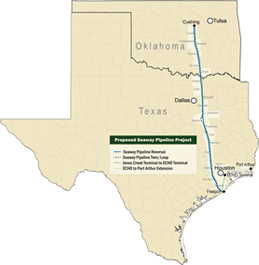

The 12-person jury found that Houston-based Enterprise Products Partners had formed a legal partnership with Dallas-based Energy Transfer Partners in 2011 to jointly build a pipeline from Cushing, Okla. to the Gulf Coast and that Enterprise violated that partnership when it ended its deal with ETP to do a more financially rewarding joint venture with Enbridge Inc.

The jury, in a 10-2 decision, ordered Enterprise to pay ETP $319 million in damages for violating the corporate version of a common law marriage.

The verdict, however, was not a complete victory for ETP. The jury found that Canada-based Enbridge did not conspire with Enterprise to cut ETP out of their joint venture.

Legal experts say that the jury’s verdict sets a potential precedent by establishing new guidelines for what constitutes a business partnership under Texas law, which has historically been relatively undefined.

“This is going to be a case cited for a long time on the issue of when a relationship becomes a partnership,” said ETP’s lead lawyer Mike Lynn, a partner at Lynn Tillotson Pinker & Cox.

In a prepared statement, Enterprise Senior Vice President James Cisarik said Enterprise does not find the verdict to be supported by the evidence in the trial and that the company will “promptly seek to reverse” the jury’s findings.

“We do not have unintended corporations, LLCs, or LLPs in business, and we should not have unintended partnerships,” the statement said.

Jeffrey Nobles, an appellate law expert at Beirne, Maynard & Parsons in Houston, said the decision is “a very important case in the Texas justice system.”

“The damage numbers are immense for most human beings like you and me, but the amounts generated in the pipeline business are so great that it’s not terrible news for Enterprise shareholders,” said Nobles. “But it may be a big deal for management and legal departments, who are under a lot of pressure these days to avoid major hits and bad publicity, and to control their legal budgets.”

Nobles added that influence of the case could open up more debate in the Texas legal and business communities about the definition of a legal partnership.

“There’s promise that this case will answer questions and create new ones for a whole generation of Texas business lawyers and their clients,” he said.

ETP asked jurors for $594 million in actual damages and double that amount in punitive damages, but because the jury verdict was not unanimous, no punitive damages were awarded.

Enterprise claimed its relationship with ETP was never a legally binding partnership and that the potential for a joint venture fell apart when Double E failed to attract enough oil and gas companies as customers.

Enterprise argued that each agreement signed for the Double E project was written so that either party could walk away from the project at any time with no binding legal obligation.

The five-week trial featured testimony from more than a dozen senior executives from the three giant oil and gas companies. Lawyers bombarded jurors with hundreds of internal corporate documents, emails, memos, joint operating agreements, marketing materials and filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission – many of those documents painted conflicting portraits of the relationship between ETP and Enterprise.

Regan Lee, one of the jurors in the case, said the decision was not difficult because she found ETP’s witnesses more genuine than those for Enterprise and Enbridge and she thought the Lynn Tillotson legal team was extremely prepared to prove ETP’s case.

“It felt like the Enterprise witnesses were used car salespeople,” she said.

Other jurors said that ETP’s Chief Executive Officer, Kelcy Warren, especially appealed to jurors, who openly expressed his feelings of betrayal when he learned about Enterprise’s decision to dump ETP and do another pipeline project with Enbridge.

“When he said, ‘Go to frickin’ church,’ he had me,” said Maryanne Denning, another juror.

Counsel for Enbridge also expressed relief that the jury did not find it liable for conspiracy against ETP.

“We’re pleased with the verdict as it related to Enbridge,” said Enbridge’s lead lawyer Michael Steinberg, a partner at Sullivan & Cromwell in Los Angeles.

ETP originally sought up to $1.3 billion in actual and exemplary damages. ETP could gain more in damages than the $319 million, depending on the outcome of Judge Emily Tobolowsky’s pending decision on awarding any additional amount of restitution.

In addition to the jury not siding with ETP on its conspiracy theory, Enterprise did prevail in one other matter. The jury decided that ETP owes Enterprise $814,148 in damages for ETP’s failure to comply to a certain section in a reimbursement agreement that the two companies signed in 2011 for its proposed Double E joint venture.

A beaming Lynn said he was overcome with a “feeling of relief” when he heard the jury’s verdict.

“We felt enormous responsibility to ETP and grew to really love those guys,” Lynn said. “I’m proud of our team.”

The three oil and gas giants hired some of the best and most expensive lawyers to fight their sides of the argument in the month-long trial. Their legal teams filled all the spots at the attorney tables and a majority of the audience gallery.

Prominent in-house counsel for the three companies were present for the whole trial, including ETP Associate General Counsel and Head of Litigation Tonja De Sloover, Enterprise Vice President of Litigation Raymond Albrecht and Enbridge Vice President of U.S. Law & Deputy General Counsel Chris Kaitson.

In addition to Lynn, ETP’s legal team included Christopher Akin, Jeremy Fielding and David Coale, also from Lynn Tillotson.

Houston lawyer David Beck of Beck Redden and Dallas attorney Richard Sayles of Sayles Werbner led Enterprise’s team. Other attorneys involved included Joe Redden, Jr., Jeff Golub and Jas Brar of Beck Redden and Shawn Long of Sayles Werbner.

Dallas attorney Jeffrey Levinger was the only Texas-based attorney for Enbridge’s team.

Dallas Jury Deliberates Billion-dollar Dispute Between ETP, Enterprise & Enbridge

By Natalie Posgate and Mark Curriden

Staff Writers for The Texas Lawbook

DALLAS (March 3) – Jury deliberations start Monday in a billion-dollar dispute involving three giant oil and gas companies over a joint effort to build a pipeline from Cushing, Okla. to the Gulf Coast.

The dozen Dallas jurors will decide whether Energy Transfer Partners of Dallas and Houston-based Enterprise Products Partners had legally formed a partnership called “Double E” to build an oil pipeline from Cushing, Okla. to Houston and whether Enterprise conspired with Enbridge to eliminate ETP from the effort in order to form a more financially rewarding deal together.

Dallas-based ETP is seeking $594 million in actual damages and double that amount in punitive damages from its two competitors. Enterprise and Enbridge argue there was no partnership with ETP and that they don’t owe a dime.

“Your verdict in this case will govern the morality of conduct in the oil and gas business in Texas for the next 10 or five years,” Mike Lynn, a lawyer representing Energy Transfer Partners, told jurors in closing arguments last Thursday.

While the damage amounts being sought soar into 10 digits, energy companies across Texas are closely watching the case because the jury’s verdict is likely to determine the point at which a proposed joint venture becomes a legal partnership.

“A lot of lawyers and businesses are watching this case very closely because the implications are huge,” said Michael Gruber, a partner at Gruber Hurst Johansen Hail Shank in Dallas.

“Until this case, most lawyers and business leaders were not aware that Texas law considers other factors, such as appearance and conduct, in determining whether a partnership is legally binding,” says Gruber. “The surprising element is that even if you don’t intend to be partners, Texas law may actually view your joint actions as a legally binding partnership based on other factors.”

Houston corporate energy lawyer Jim Rice agrees the case is the talk of the oil and gas industry.

“Many lawyers are watching this case very closely because it could have significant ramifications for corporations doing business in Texas,” says Rice, a partner at Sidley Austin in Houston. “This is a very significant case.”

David Poole, the general counsel of Dallas-based Range Resources, says the ETP case is getting a great amount of attention within the energy community in particular.

“The legal question of what facts must exist for a relationship to become a legally recognized JV or partnership is relatively undefined, which makes this case and the jury’s verdict very important to Texas businesses,” says Poole.

“There are a lot of general counsel watching to see how the jury rules in this case,” he says. “It could have a major impact on how businesses operate.”

Poole and Gruber say they don’t envy the jury’s mission, as lawyers for the three companies bombarded them with hundreds of internal corporate documents, emails, memos, joint operating agreements, marketing materials and filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

More than a dozen top executives from ETP, Enterprise and Enbridge testified during the five week trial, including ETP Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Kelcy Warren, who told jurors that if he had known that ETP would be eliminated from the Double E partnership, he would have asked Enterprise for a “bullet-proof jacket” when the two companies started talking.

“Show me a document [that says] any party has the right to eliminate another party,” Warren told jurors. “Go to frickin’ church. Have a parent. Have a moral compass. You’ve got to be kidding me.”

Photo courtesy of dallasnews.com

Enterprise claims there was never an official partnership with ETP and that the proposed joint venture was not economically viable.

Houston lawyer David Beck, the lead counsel for Enterprise, repeatedly pointed to multiple agreements between Enterprise and ETP specifically stating there was no partnership, including an April 27, 2011 document signed by ETP and Enterprise that stated, “Nothing shall be deemed to create or constitute a joint venture, partnership” unless the corporate boards of both companies approved it.

And he pointed to internal emails and memos by ETP and Enterprise executives from the summer of 2011 saying they were still waiting for the joint venture or partnership to be finalized.

“What better expression of the parties’ intent than what they agreed to in writing,” Beck told jurors.

Enterprise CEO Michael Creel testified that he repeatedly wanted it emphasized in documents that there was no legal partnership with ETP and he said he was “stunned” when ETP filed its lawsuit.

Creel said joint operating agreements with ETP specifically stated that there was no binding partnership and that it would require approval of the boards of directors of both companies to make it a binding joint venture.

Enterprise management never brought the project to the board because “we didn’t have a project that could stand alone,” Creel told jurors.

Creel and former Enterprise executive Mark Hurley testified that the words “joint venture” and “partnership” are common lingo terms in the oil and gas industry that mean two companies simply agreed to work together but are not intended to be interpreted in a legal sense.

Hurley said that the agreements between ETP and Enterprise were always written so that either party could walk away at any time.

“Both sides wanted to be able to walk away with no issues,” he told jurors. “It is the most common kind of relationship. What we had with ETP was a very standard situation.”

But ETP’s lead lawyer, Mike Lynn, showed jurors dozens of memos, emails and marketing materials supporting the argument that the two companies had formed a joint venture. He pointed to marketing materials that both companies presented to potential shippers in summer 2011. “Enterprise and Energy Transfer have formed a Joint Venture LLC,” read one line.

“We’ve showed you more than 90 instances where the companies say they were involved in a joint venture,” Lynn told jurors. “You’re the only set of people in the world who they have not said they were joint venture partners to.”

Lynn said that ETP and Enterprise agreed to share profits and expenses for the proposed joint venture, made mutual expressions of intent to be partners, and agreed to participate in the control of the business – all definitions of a business partnership as defined by Texas law.

The problem for Enterprise, Lynn told jurors in closing arguments, is that business partnerships are legally formed under Texas law even when the parties do not intend to create a partnership. He compared it to common law marriages in which the couple may not want to be married but are still considered legally married because they live together, bank together or have children together.

Showing a photograph of a duck, Lynn told jurors, “It looks like a partnership. It walks like a partnership and acts like a partnership. This duck was a partnership.”

However the jury votes, business lawyers say the case has attracted attention of the corporate leaders, especially in the oil and gas industry.

“A lot of businesses, especially in the energy sector, have these loose partnership deals,” says Jonathan Henderson, a partner at the Polsinelli law firm in Dallas. “This case will cause business leaders and business lawyers to be much more attentive to these relationships.”

To be sure, none of the three oil and gas companies are mom-and-pop shops desperate for money nor is this a bet-the-company case for any of them. ETP reports $50 billion in assets and has an active line of credit of nearly $2 billion available. Enterprise has $38 billion in assets and Enbridge counts $30 billion in assets.

The three energy companies hired some of the best and most expensive lawyers – and lots of them, as their legal teams filled all the spots at the attorney tables and more than two-thirds of audience gallery.

ETP, Enterprise & Enbridge Present Clashing Closing Arguments

By Natalie Posgate and Mark Curriden

Staff Writers for The Texas Lawbook

DALLAS (February 27) – Enterprise Products and Enbridge Inc. secretly and spitefully conspired to eliminate Dallas-based Energy Transfer Partners out of a multibillion dollar partnership to build an oil pipeline from Cushing, Okla., to Houston in 2011, lawyers for ETP told Dallas jurors in closing arguments Thursday.

“They stole something. They did it intentionally. They did it maliciously and they did it because they are greedy,” said ETP lead lawyer Mike Lynn.

But David Beck, the lead lawyer for Houston-based Enterprise, told jurors that ETP’s lawsuit is “nothing more than a partnership by ambush.”

Thursday’s closing arguments capped four weeks of intense testimony that featured two-dozen witnesses and thousands of internal documents from the three huge oil and gas corporations.

The key technical question for jurors is whether ETP and Enterprise legally formed a partnership or joint venture in 2011 when they teamed up to consider building the oil pipeline.

ETP is also asking jurors to determine that Enterprise and Enbridge conspired to harm ETP by cutting it out of the deal they entered after ETP and Enterprise’s “Double E” pipeline joint venture failed in its open season.

Enbridge claims that it did not know Enterprise and ETP had entered a partnership and had no reason to believe that they did. Enbridge also contends that it was merely Enterprise’s backup plan, and that Enterprise made it clear that it would go with Double E if the project gained sufficient shipper commitments.

“It is wrong to sue in court for what you failed to achieve in the market,” said Los Angeles-based Sullivan & Cromwell partner Michael Steinberg, Enbridge’s lead lawyer.

“Enbridge has tried to respect being the backup,” he added. “Enbridge never knew of a partnership. Enbridge knows about its [own] business; it does not know about imaginary partnerships.”

Enterprise claims there was no legal partnership and points to four separate documents jointly issued by the two companies that explicitly state there wasn’t. For example, an April 27, 2011 agreement signed by ETP and Enterprise reads, “Nothing shall be deemed to create or constitute a joint venture, partnership.”

“What better expression of the parties’ intent than what they agreed to in writing,” Beck told jurors.

But Lynn pointed to “90 instances” in which leaders of the two companies said they were joint venture partners in marketing brochures, internal emails and other records.

Lynn told jurors that business partnerships are legally formed under Texas law even when the parties do not intend to create a partnership. He compared it to common law marriages, in which the couple may not want to be married but are still considered legally married because they live together, bank together or have children together.

Showing a photograph of a duck, Lynn told jurors, “It looks like a partnership. It walks like a partnership and acts like a partnership. This duck was a partnership.”

Beck said he took Lynn’s marriage allusion personally.

“I view my marriage as sacred; a promise I made over 40 years ago, and I kept that promise,” Beck said. “To talk about a deal put together by lawyers and senior management that says it’s non-binding – that’s not my idea of a marriage.”

ETP is seeking $594 million in actual damages and double that in punitive damages.

The 12-person jury will start deliberating its decision Monday.

Enbridge Witnesses: There Was Never a Ring on Enterprise’s Finger

By Natalie Posgate

Staff Writer for The Texas Lawbook

DALLAS (February 24) – Key witnesses for Canada-based Enbridge Inc. explained to jurors Monday that the proposed Double E joint venture between Enterprise Products and Energy Transfer Partners is much like the societal standards in romantic relationships: Enbridge did not see a ring or a marriage license, so there was no marriage.

“You saw a ring on the finger of ETP, and because some women wear rings and some don’t… you assumed [ETP and Enterprise] weren’t married? ETP’s lead trial lawyer, Mike Lynn, asked Enbridge’s first witness, Vincent Paradis.

“I didn’t see a ring,” replied Paradis, Enbridge’s director of market development.

Paradis made the debut in week five of the big-dollar trial between ETP, Enterprise and Enbridge. ETP claims that Enterprise violated their partnership to join forces with Enbridge, and that the two conspired together to cut ETP out of a pipeline deal, which ETP claims cost it potentially billions in damages for the lost opportunity.

Enbridge and Enterprise disagree. Both claim there was no partnership for the proposed “Double E” joint venture between ETP and Enterprise, which would build a crude oil pipeline from Cushing, Okla. to Houston. They claim a partnership never formed because Double E never legally became an LLC.

Throughout cross-examination, Lynn pressured Paradis to admit that Enbridge purposely did not question whether Double E was a partnership when it started talking to Enterprise about working on a similar Cushing to Gulf Coast pipeline project because Enbridge knew deep down that it was one. Lynn displayed various emails and other documents to the state jury that called Double E a joint venture or partnership.

Paradis said there was never a need to question ETP and Enterprise’s relationship and Enbridge never did question it because in the business world, “partner” and “joint venture” are used “in a loose fashion.”

“You don’t form a binding partnership until you actually have a project,” Paradis said, alluding Double E’s failure to become economically viable due to the lack of committed shippers that it attracted in its open season.

After Paradis testified, jurors saw a couple of video depositions, including ETP’s Senior Vice President of Engineering John Phillips, who was involved with the Double E project. He told Enbridge’s lawyers that from an engineering standpoint, “joint venture” simply is a term for a project that a company is not doing by itself.

But when ETP’s lawyers cross-examined Phillips, he said that in May 2011 (which was after ETP and Enterprise announced their proposed Double E joint venture to the public), both parties agreed to work together under the presumption that the joint venture had officially formed.

Enbridge’s final key witness took the stand Monday afternoon. Steve Wuori, Enbridge’s vice president of liquids pipelines and major projects, echoed Paradis’ opinion about using the words “joint venture” and “partner,” adding that he usually does not mean them in a legal sense when he uses them.

He said companies usually do not immediately enter a partnership when they decide to pursue a joint venture because first they need to see if a project even exists.

Wuori will continue his testimony on Tuesday.

Update: Ex-Enterprise Exec Says Calling ETP a Partner was a Mistake

By Natalie Posgate

Staff Writer for The Texas Lawbook

DALLAS (February 20) – Key Enterprise Products witness Mark Hurley told jurors during three days of testimony that any statement by Enterprise that made it appear that the Houston-based oil and gas company had formed a partnership with Energy Transfer Partners regarding their Double E project was a mistake.

ETP pointed jurors in the billion-dollar dispute to a 2011 document the two companies prepared as marketing materials to attract potential shippers to a proposed Cushing, Okla. to Houston pipeline as proof that Enterprise and ETP had legally formed a partnership and joint venture.

The document specifically states that Enterprise and ETP “have formed a joint venture,” which contradicts Enterprise’s central argument that a joint venture was never formed between the two pipeline companies.

Jeremy Fielding, one of ETP’s attorneys, asked Hurley if that sentence was a mistake, and he said yes. Hurley, Enterprise’s former vice president of crude oil and offshore business unit, explained that the company’s lawyers did not review the informal documents related to Double E – only the ones that could involve legally binding statements.

Whether or not Enterprise and ETP legally formed a partnership in 2011 for their proposed joint venture Double E project is the primary question in this billion-dollar trial, which ETP initiated. The Dallas-based energy company claims that Enterprise wrongfully terminated the two companies’ legally binding joint venture to continue a similar pipeline project with Enbridge – one that ETP claims it was cut out of.

Enterprise and Enbridge argue that Enterprise had no binding legal obligation to ETP to not speak to Enbridge while Double E was still in existence, that neither company was obligated to tell ETP about their new project and that they didn’t because ETP would not have brought any value to the table.

Fielding also tallied for the state jury seven times that Hurley didn’t agree with something summarized by Enbridge executives regarding what Hurley said about Enterprise and ETP’s relationship or what Enterprise told Enbridge regarding shipping commitments it could bring to their new project.

One tally involved an internal Enbridge email written by Vern Yu that said once the open season for Double E ended, Enterprise planned to end its joint venture with ETP. Hurley denied that he worded it that way to Yu when they spoke.

Hurley said it “was the absolute truth” that he told Enbridge that Enterprise would go with ETP if Double E gained sufficient shippers by the end of its open season.

Another tally involved an internal Enbridge email from Pat Daniel to Vern Yu that said Enterprise told Enbridge it had commitments from Chesapeake Energy that it could bring to the table in Enterprise and Enbridge’s new project, which they formed after Enterprise its Double E joint venture with ETP.

Fielding asserted that Chesapeake came to the project, initially called Wrangler, because its commitment to Double E carried over to Wrangler. Hurley denied that allegation, pointing out that Chesapeake claimed its shipping commitment to Double E “null and void” after the open season ended, since the proposed joint venture had terminated. He added that Enterprise and Enbridge had to open up new negotiations with Chesapeake for the Wrangler project, which he described as much more difficult.

Fielding asked Hurley if he had heard the phrase, “If it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck, and walks like a duck, then it probably is a duck.” Fielding then compared Enterprise and ETP’s relationship to the ducks.

“ETP and Enterprise made the decision to start walking like partners, talking like partners and calling themselves partners,” he said.

He implied that what Enterprise did with the marketing materials and other documents met that description.

Fielding also brought up a section of the Enterprise-ETP confidentiality agreement addressing publicity that stated one party could not issue press releases, public announcements and other documents without the prior written consent of the other party.

He then confronted Hurley about the fact that Enterprise issued a press release about the proposed Double E joint venture on Friday, Aug. 19, 2011, despite ETP “pleading” with Enterprise to hold off issuing it until the following Monday.

Hurley said an exception applied to this situation that involved a Securities and Exchange Commission rule that requires companies to disclose major updates to their business ventures to all investors at the same time – something he and other Enterprise executives testified needed to be done since the information about Double E ending was already traveling so fast.

Lead Enterprise lawyer David Beck displayed this exception in the term sheet, which stated that parties could release information to the public if they were legally compelled to do so to comply with regulations of the SEC and New York Stock Exchange.

But later, Fielding highlighted “the rest of” the same paragraph that said if one party felt legally compelled to report information regarding Double E, it must provide a five-day written notice to the other party that it will do so.

Fielding pointed out that Enterprise’s Vice President of Public Relations, Rick Rainey, previously testified that he gave ETP three hours of notice about the press release. Hurley did not deny the validity of Rainey’s testimony.

During Hurley’s direct examination Tuesday, he said that Energy Transfer Partners’ interest in their Double E project “definitely diminished” during its unsuccessful open commitment period with shippers.

“To hear your potential partner in an LLC come with the message that they were getting discouraged was frustrating,” said Hurley, who is currently the Chief Executive Officer of Blueknight Energy Partners.

When Hurley called ETP President Mackie McCrea at the end of Double E’s 80-day open season to tell him that Enterprise was withdrawing from the proposed project since not enough committed shippers were secured to make the project economically viable, “it was a very friendly conversation.”

He said the term sheet that both parties signed for their Double E project took several weeks to complete because it went back and forth until both parties were happy – including lawyers on both sides.

Beck displayed the non-binding agreement in the term sheet for the jury, which Hurley explained meant that at any time one party could call the other and say it was terminating the agreement with no binding legal obligation.

The non-binding agreement was something ETP “absolutely” wanted, too, Hurley said.

“ETP wanted the same thing,” he said. “[Both sides] wanted to be able to walk away with no issues.”

Hurley said he was one of the executives who led Enterprise’s efforts for Double E, such as visiting the offices of potential shippers and communicating with ETP about the project.

A potential shipper that looked promising was Lyondell, he said, which he had “positive discussions” with about committing to the Double E project. Hurley’s last meeting with Lyondell was in July 2011 – a meeting that he said was so good that at the end of it, he received a company T-shirt, which he said is “a big deal” in the business world.

The positivity was short-lived because Lyondell called two weeks later (and days before the open season expired) to say that it would not commit, which Hurley described as very disappointing.

“We had high hopes for Lyondell,” he said.

After Hurley called McCrea to terminate Double E (and, as he described, the conversation ended on a positive note), ETP Senior Vice President Lee Hanse sent a letter to all ETP and Enterprise executives who were involved saying that the “proposed joint venture” had ended. Hurley said the letter contained phrases like “to work toward” and “to negotiate” – phrases that indicated no partnership had legally been established. He said Hanse’s views in the letter were in line with all of Enterprise’s views about Double E.

During Enbridge’s cross-examination of Hurley, Robert Giuffra of Sullivan & Cromwell displayed the Aug. 19, 2011 press release that announced Enterprise and ETP’s proposed joint venture had been terminated. He asked Hurley if ETP objected to using the phrase “proposed joint venture,” and Hurley testified that the first time he heard ETP object to that phrase was when it filed its lawsuit against Enterprise and Enbridge in September 2011.

Hurley told Giuffra and the jury that for every project Enterprise goes forward with, there are probably five that the company walks away from that, like Double E, were non-binding early on.

“It is the most common kind of [business] relationship,” Hurley said. “What we had with ETP was a very standard situation.”

When Beck concluded his questioning with Hurley, he brought up the fact that Hurley voluntarily testified for this trial – and for no compensation – since he is no longer with Enterprise. Hurley said he decided “early on” that he was going to testify because working at Enterprise meant something to him and he didn’t approve of the “lying, betrayal and deception” that ETP has put forth in this legal dispute. He said it’s the first time he’s seen a company cope with an unsuccessful project – something common in his field – with a lawsuit.

Enbridge called up its first witness, Vincent Paradis, at the end of Thursday. Paradis is currently Enbridge’s director of market development. His testimony will continue next week.

Ex-Enterprise Exec: Ending Double E JV with ETP was a Friendly Conversation

By Natalie Posgate

Staff Writer for The Texas Lawbook

DALLAS (February 19) – One of Enterprise Products’ key witnesses told a state jury Tuesday that Energy Transfer Partners’ interest in their Double E project “definitely diminished” during its unsuccessful open commitment period with shippers.

“To hear your potential partner in an LLC come with the message that they were getting discouraged was frustrating,” said Mark Hurley, Enterprise’s former vice president of crude oil and offshore business unit.

When Hurley called ETP President Mackie McCrea at the end of Double E’s 80-day open season to tell him that Enterprise was withdrawing from the proposed project because not enough committed shippers were secured to make the project economically viable, “it was a very friendly conversation.”

Hurley’s termination of the Double E project is part of the heart of the argument in Enterprise’s billion-dollar trial with ETP, which claims that Enterprise wrongfully terminated the two companies’ legally binding joint venture to continue a similar pipeline project with Enbridge.

But Hurley reiterated Enterprise’s position that it never had a legally binding partnership with ETP during his testimony.

He said the term sheet that both parties signed for their Double E project, which would build a crude oil pipeline from Cushing, Okla. to Houston, took several weeks to complete because it went back and forth until both parties were happy – including lawyers on both sides.

Enterprise’s lead attorney for the trial, David Beck, displayed the non-binding agreement in the term sheet for the jury, which Hurley explained meant that at any time one party could call the other and say it was terminating the agreement with no binding legal obligation.

The non-binding agreement was something ETP “absolutely” wanted, too, Hurley said.

“ETP wanted the same thing,” he said. “[Both sides] wanted to be able to walk away with no issues.”

Hurley’s testimony will continue Wednesday, beginning with cross-examination by ETP and Enbridge.

Jurors also heard Tuesday from Enterprise’s expert witness. Financial valuation consultant David Fuller said he disagreed with ETP’s expert witness Jeff Makholm, a pipeline economist who concluded that ETP deserves at least $595 million in damages for its missed opportunity to take part in the Seaway Pipeline joint venture, which Enterprise formed with Enbridge after it terminated Double E with ETP.

During cross-examination, one of ETP’s lawyers, Chris Akin, asked Fuller if he performed an independent calculation of the damages owed to ETP. Fuller replied that he was not asked to do that – only to evaluate Makholm’s.

Enterprise CEO: ‘Joint Venture’ Never Meant in a Legal Sense

By Natalie Posgate

Staff Writer for The Texas Lawbook

DALLAS (February 17) – Enterprise Products Chief Executive Officer Michael Creel told jurors Monday that his company’s proposed “Double E” joint venture with Energy Transfer Partners never became a legally-binding partnership and he was “shocked” when ETP claimed so in its lawsuit against Enterprise and Enbridge.

Creel said that Houston-based Enterprise considered multiple options over the past several years to build a Cushing, Okla. to Texas Gulf Coast pipeline and that working with ETP to utilize its Old Ocean Pipeline into the plan was not the first.

Creel is Enterprise’s first witness in its state jury trial against ETP, which claims that Enterprise violated its partnership with ETP by secretly joining forces with Enbridge to build a similar pipeline as the Enterprise-ETP Double E project.

Enterprise and Enbridge refute the claims and argue that ETP never legally formed a partnership with Enterprise, let alone a joint venture. They also claim that the project that Enterprise and Enbridge talked about during Double E’s open season was different from Double E.

One of Enterprise’s other pipeline considerations occurred in 2010, when it explored a joint venture possibility with Enbridge that would involve Enbridge’s Monarch project, which would flow crude oil from Canada to the Gulf Coast. Like it had done with ETP, Creel testified that Enterprise and Enbridge entered a confidentiality agreement at the time, but their initial discussions involving the Monarch project did not go anywhere.

He said both Enterprise and Enbridge had discussed approaching ETP about the possibility of utilizing its Old Ocean Pipeline to connect Cushing and Houston, and Creel finally did so in February 2011.

When Enterprise and ETP agreed to pursue the joint venture called Double E, Creel said none of the documents the two parties signed contained legally binding language. In fact, a crucial element of proof that Double E never became a partnership is that neither ETP nor Enterprise had their boards of directors approve the project, he said.

Enterprise management never brought the project up to its board because “we didn’t have a project that could stand alone,” Creel said.

Before the April 26, 2011 press release was published that announced Enterprise and ETP had agreed to form a joint venture, Creel testified that he reviewed it to make sure it contained no legally binding language, like he had done with the non-binding term sheet – the document that Creel said established that there in fact was no legally binding obligations between Enterprise and ETP and that either party could terminate the proposed joint venture.

Throughout Enterprise’s talks with ETP, Creel said he was very upfront about the fact that Double E was not a legal partnership, that their terms were non-binding and that Enterprise would pursue other options if Double E could not gain committed shippers at the end of its open season.

Creel said he also warned ETP about its ongoing talks with ConocoPhillips, which, at the time, Enterprise shared a 50/50 ownership interest in the Seaway Pipeline, which connects Cushing to Houston but originally flowed from South to North. He said Conoco would not agree to reverse the flow of the pipeline, but if it changed its mind, Creel “made it clear” to ETP that Enterprise would choose Conoco for its Cushing to Houston pipeline efforts and would only work with Conoco.

Conversely, Creel told jurors that when Enterprise and Enbridge began considering a joint venture in August 2011, Enterprise made it “crystal clear” to Enbridge that if Double E obtained sufficient shipper commitment by the Aug. 12 expiration date of its second open season, Enterprise would go with ETP for its efforts to build a Cushing to Texas Gulf Coast pipeline.

According to Creel, it became “abundantly clear” to him that there were problems with making Double E economically viable during its open season in June, July and August 2011 because only one shipper, Chesapeake Energy, had committed. He said Enterprise began talking with Enbridge to form a back-up plan in case Double E did not seal down more shippers by the end of its second extension of its open season – something he said sends the message to potential shippers “that you’re desperate.”

During cross-examination, ETP’s lead trial lawyer, Mike Lynn, pulled up an Aug. 3, 2011 internal Enbridge email from one company executive instructing another to keep the information “tight,” which was that there was a potential of Enbridge “teaming up on Double E” with Enterprise. The email contradicted previous testimony that Enbridge and Enterprise were in talks about a separate project from Double E when it was still in existence.

Lynn pulled up another internal Enbridge email among company executives from Aug. 23, 2011 – after Enterprise terminated Double E and after Enterprise and Enbridge agreed to work together. It said that Enterprise wanted to defer releasing a statement announcing its new joint venture with Enbridge because it was sensitive of “dropping one partnership and widely broadcasting another partner immediately.”

Chesapeake Energy’s senior vice president of marketing, Jim Johnson, testified by video deposition late Monday afternoon that “joint venture” and “partner” are often loosely used terms among the business community that simply mean two parties are “trying to do a project together” but do not mean anything legally binding.

ETP CEO: ‘Enterprise Did Not Lay All its Cards on the Table’

By Natalie Posgate

Staff Writer for The Texas Lawbook

DALLAS (February 14) – Energy Transfer Partners Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Kelcy Warren told jurors Thursday that Enterprise “did not lay all its cards on the table before walking away” from its Double E joint venture with ETP.

The missing cards, according to Warren, are at the heart of ETP’s claims that Enterprise talked to Enbridge about building a similar pipeline to Double E while still in a partnership with ETP – claims that put the stakes of the trial at potentially billions of dollars.

“I expect my partner to put down their full hand of cards,” Warren said. “I’ll stand and play; I’m not going to fold.”

Warren said there was no problem with Enterprise withdrawing from the Double E project, but he viewed the next steps as a betrayal, claiming Enterprise continued to work on it and ultimately eliminated ETP from it by partnering with Enbridge.

Photo courtesy

dallasnews.com

“Show me a document [that says] any party has the right to eliminate another party,” Warren said. “Go to frickin’ church. Have a parent. Have a moral compass. You’ve got to be kidding me.”

If Enterprise had asked ETP about adding Enbridge to the Double E project, Warren said his hindsight today is confirmation. “I’m confident we’d say, ‘Bring Enbridge in.’”

Enterprise and Enbridge dispute that they did anything wrong. They argue that no legal partnership had ever been formed for Double E, that Enterprise and ETP never signed an exclusivity agreement, that it is standard practice for companies to have back-up plans if a project with another company does not work out and that Enterprise drew away from the Double E proposal because it could not lock down committed shippers to make the project economically viable.

Warren said ETP and Enterprise first entertained the idea of starting a joint venture when he received a call from Enterprise Chief Operating Officer Jim Teague in March 2011. The two agreed to a meeting in Warren’s home, where they discussed building a Cushing, Okla. to Houston pipeline – a large component of which would be made up by ETP’s existing Old Ocean Pipeline.

Both parties were excited about the idea and agreed it was something they should look into, he said.

“The value Teague suggested we would make as partners was the biggest value I’d heard in my career,” Warren said.

In the next month, ETP and Enterprise agreed to form a joint venture and issued a press release on April 26, 2011 announcing it to the public. On May 25, Double E issued another press release that announced the beginning of its open commitment period for potential shippers.

At a meeting on June 30, Warren said Enterprise wanted to abandon the Old Ocean Pipeline in the plan, and Warren was skeptical. Both parties also discussed the possibility of bringing in a new partner to the joint venture and both were open to it.

Enterprise CEO Michael Creel “talked for an unusually long time” about ETP’s financial viability in the project, Warren said. Then, Creel asked if ETP would ever want to leave the project and Warren replied, “We’re in.”

ETP’s lead trial lawyer, Mike Lynn, pulled up an internal Enterprise email that Jake Everett, a company executive, sent to Director of Project Development John Macon after the meeting that said ETP still wanted to stay on the project.

Macon’s reply email read: “F———————-KKKKKKKKKK!

Warren said he hadn’t seen this email until close to trial. “I’d like to say this says ‘fantastic,’” he joked.

During cross-examination, Sullivan & Cromwell partner Robert Giuffra pulled up an Aug. 11, 2011 internal e-mail between Enbridge’s senior vice president of business and market development Vern Yu and other Enbridge executives that discussed details from a recent meeting Enterprise had with Enbridge to explore options for building a pipeline from Cushing to Houston.

Yu wrote in the email that Enterprise executive Mark Hurley told Enbridge that if Double E received enough shipper support by Aug. 12 (the ending date of the project’s open season), Enterprise would go with ETP.

Giuffra questioned Warren if ETP ever comes up with back-up plans for business ventures to make the point that they are standard among the business community and that Enterprise and Enbridge’s communications were merely part of a back-up plan.

Giuffra and Enterprise’s lead lawyer David Beck pointed out that the press releases announcing the Double E joint venture, the beginning of Double E’s open season and the termination of the joint venture all include the words “proposed pipeline” and “would,” which they said indicates the joint venture was only proposed and never officially formed and that these phrases were used in the press releases because the developments may or may not happen.

Beck displayed an Aug. 8, 2011 quarterly report that ETP filed with the SEC and asked Warren if the Double E project was listed under recent developments to make the argument that the transaction was never developed enough to be included. Despite the filing taking place during the open shipper commitment period, Double E was not listed.

After Warren left the stand, the jury heard from Teague of Enterprise by video deposition. Teague testified that Enterprise had been involved with proposed joint ventures before ETP to build a pipeline from Cushing to Houston. In 2010, Enterprise and Enbridge entertained the idea, but it didn’t work out.

“Talking about a deal and doing a deal are two different things,” Teague said.

ETP finished its presentation to the jury at the end of Thursday. Enterprise and Enbridge will begin to call up their own witnesses next week.

ETP Expert Witness: Enterprise-Enbridge JV Not Possible Without ETP — Updated

By Natalie Posgate

Staff Writer for The Texas Lawbook

DALLAS (February 12) – Energy Transfer Partners’ expert witness told jurors Tuesday that the Seaway Pipeline joint venture between Enterprise Products and Enbridge “would not be the Seaway today” if not for the creation of the Double E project that originally involved ETP.

Expert pipeline economist Jeff Makholm’s viewpoint is that since Seaway is essentially the same pipeline as the would-have-been Double E project, ETP in turn suffered significant damages – at least $594 million – because it was excluded from the Enterprise-Enbridge joint venture.

ETP is asking a state jury to award $1.3 billion in actual and punitive damages because it says Enterprise improperly ended its partnership to build the pipeline so Enterprise could do a better deal with Enbridge, another competitor.

Makholm said the main value of Seaway originated from Double E’s ability to secure Chesapeake Energy as a shipper, which Enterprise in turn brought to the Seaway project after terminating Double E with ETP.

He said the value of Chesapeake’s shipping commitment could be compared to the value a Wal-Mart store’s commitment would be if it became a vendor of a new strip mall.

“Double E and Seaway shipped from the same starting point to the same ending point and contained the same shippers,” said Makholm, the senior vice president at National Economic Research Associates (NERA), the country’s oldest economic consulting firm. “It’s the same project.”

Makholm also issued his opinion that ETP deserves one-fourth of the value of the Seaway project because it was essentially the connection of Enterprise’s separate 50/50 joint ventures with Enbridge and ETP.

Seaway Crude Pipeline Company LLC is the product of a 50/50 joint venture between Enterprise and Enbridge that includes a 500-mile, 30-inch pipeline between Cushing, Okla. and Houston. Enterprise and Enbridge’s project was originally to be called the Wrangler Pipeline, but that changed in November 2011 when Enbridge purchased ConocoPhillips’ 50 percent ownership interest in the Seaway Pipeline for $1.15 billion.

In May 2012, Enterprise and Enbridge completed a project to reverse the flow direction of the Seaway Pipeline (which originally ran from Houston to Cushing), which Makholm said was the crucial puzzle piece all major oil companies have tried to solve to transport valuable crude oil in Alberta, Canada to refineries in the Gulf Coast.

Before Seaway, Enterprise and ETP explored this puzzle by forming a joint venture in April 2011 to build the Double E Pipeline from Cushing to Houston. Witnesses have testified that Enterprise approached ETP about forming the venture because it thought ETP’s existing Old Ocean Pipeline, which already connected the DFW and Houston areas, would be a valuable component since it would save steps.

Enterprise ended the joint venture with ETP after its open season to seal commitments from shippers expired, claiming “the project wasn’t viable.”

ETP claims by doing so, Enterprise violated their partnership by conspiring with Enbridge to cut ETP out of the new project.

Enterprise and Enbridge are denying the allegations, arguing that Enterprise and ETP had never entered a partnership to begin with and that their relationship was merely non-binding in nature.

During cross-examination Wednesday, Jeff Golub, who represents Enterprise, questioned the validity of Makholm’s opinion that Chesapeake’s commitment to the Double E was the main contributor to the value of the Seaway joint venture.

Golub pointed out that when the Enterprise-Enbridge joint venture was still called the Wrangler Pipeline, Chesapeake was the only committed shipper – which he emphasized was the same case for the Double E project.

But when the Seaway Pipeline came in the picture, it all changed, Golub said, because it was affiliated with Enbridge’s strong foundations in projects that bring oil from the Northern United States and Canada, such as its Flannagan South Pipeline Project.

He pulled up a chart that listed the committed shippers for the Seaway project during its open season, which included a handful of big names such as ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Devon Energy, Hunt Oil and Cenovus Energy.

“They flocked like geese to that project,” said Golub, a partner at the Houston litigation boutique Beck Redden.

Before Makholm testified, jurors heard from Vern Yu by video deposition, who is Enbridge’s senior vice president of business and market development and attended meetings in 2011 with Enterprise executives to discuss forming a joint venture.

Yu testified that the initial meeting occurred before the open season for Enterprise and ETP’s joint venture was over. During the meeting, Enterprise informed Enbridge that it planned to end the joint venture with ETP once the open season ended, Yu said.

But during cross-examination, Yu told Enterprise’s attorneys that “joint venture” is a loosely used term and doesn’t define a legal partnership.

ETP’s last live witness, the company’s Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Kelcy Warren, took the witness stand at the end of Wednesday afternoon. His testimony will continue on Thursday.

ETP President Continues Stance About an Existing ETP-Enterprise Partnership

By Natalie Posgate

Staff Writer for The Texas Lawbook

DALLAS (February 4) – Energy Transfer Partners’ first witness for its multi-billion dollar dispute between Enterprise Products and Enbridge testified Monday that ETP and Enterprise formed a partnership in 2011 when the two companies formed a joint venture to build a pipeline from Cushing, Okla. to Houston.

ETP President and Chief Operating Officer Marshall “Mackie” McCrea said repeatedly through his testimony that Enterprise “was never ambushed” into stating on key documents of the joint venture that they had entered a partnership.

During McCrea’s testimony, ETP’s lead lawyer Mike Lynn spent a half-day pulling up various emails, press releases and written agreements to prove to the 12 jurors that ETP and Enterprise had legally entered a partnership and that Enterprise had wrongfully told Enbridge confidential information about the joint venture and developed talks to form a partnership with Enbridge before Enterprise had terminated its partnership with ETP.

One example was an April 26, 2011 press release announcing the joint venture between ETP and Enterprise that contains a quote from Enterprise Chief Executive Officer Mike Creel stating, “We are pleased to partner” with ETP. McCrea said that Enterprise had to approve the wording of the press release before going public because quotes of the company’s own were included.

McCrea told the jurors that by mid-May 2011, ETP and Enterprise had developed a “full-blown partnership,” and over the next three-and a half months they represented themselves as partners “in every way possible,” going through “every aspect of what partners agree on.”

But in early August, McCrea said Enterprise started secretly talking to Enbridge about forming a partnership to pursue the same kind of pipeline project, despite still having the joint venture with ETP. McCrea testified that Enterprise also revealed details of its joint venture with ETP to Enbridge during this time, which violated the confidentiality agreement ETP and Enterprise had signed.

On Aug. 12, Enterprise Senior Vice President Mark Hurley called ETP to end the partnership because “the project wasn’t viable.” By the following week, Enterprise and Enbridge entered an exclusivity agreement for their new joint venture.

Enterprise lead counsel David Beck spent the afternoon highlighting multiple documents that contained the phrase “proposed joint venture” to make the argument that ETP and Enterprise’s joint venture was never official.

He asked McCrea if he or any other ETP executives had established written amendments with Enterprise after they had developed a full-blown partnership, or if the agreements about their new status was merely oral. McCrea said the developments moved along so quickly that no amendments were ever obtained in writing.

Beck also questioned McCrea about the non-binding agreement the two companies had signed and got him to agree that it meant neither side was bound to one another at the time of the proposed transaction.

But throughout cross-examination, McCrea continually insisted that both sides knew they had a partnership with one another.

McCrea’s testimony will continue today.

ETP President to Jury: We had a Partnership with Enterprise

By Mark Curriden and Natalie Posgate

Staff Writers for The Texas Lawbook

DALLAS (January 31) – Opening statements Thursday in the billion-dollar legal battle between three oil and gas giants – Energy Transfer Partners, Enterprise Products and Enbridge – at times resembled a nasty, bitter divorce caused by lovers’ triangle.

“We were cheated on,” said Dallas trial lawyer Mike Lynn, who is representing ETP in the case that accuses Enterprise of ending their partnership in a pipeline project in order to start another relationship with Enbridge.

“This was intentional betrayal by Enterprise,” Lynn told the seven-woman, five-man jury selected to decide the case. “This was coldblooded. They kicked us out like we were dogs.”

David Beck, the lead lawyer for Enterprise, countered that the evidence would show that there was no cheating because ETP and Enterprise were never in a committed relationship from the start.

“Both parties wanted no exclusivity,” Beck told jurors. “They’re trying to create a partnership through ambush.”

Enbridge’s lead lawyer, Michael Steinberg, stuck with the theme when he addressed the jury.

“It’s not a marriage,” he said. “They will never love each other.”

Even emails between Enterprise’s Chief Operating Officer Jim Teague and the company’s CEO, Mike Creel, played into the storyline, too.

“[Enterprise Vice President] Bart Moore said his breakups with psycho girlfriends was easier than this,” Teague wrote to Creel.

“Maybe Bart’s psycho girlfriends weren’t as wacko!” Creel responded.

At the heart of the dispute is whether ETP and Enterprise legally formed a partnership in 2011 when the two energy corporations tried to form a pipeline that would transport oil from Cushing, Okla. to Houston.

Lawyers for the three energy companies used half their four hours of opening statements Thursday educating the jury about oil and gas industry and the world of pipelines, and the other half painting each other as cheating money grubbers.

Lynn, a partner at Lynn Tillotson Pinker & Cox, told jurors there are about 90 internal memos, emails and corporate public statements by Enterprise executives that demonstrate that Enterprise officials believed they had a joint venture with ETP.

For example, a press release issued by the two companies on April 26, 2011 has a headline stating, “Enterprise and Energy Transfer to Form Joint Venture.” The release states that the two companies “announced they have formed a 50/50 joint venture” and quoted Enterprise CEO that he is “very pleased to partner with” ETP.

Lynn showed jurors internal Enterprise memos and marketing materials from May and June 2011 describing the effort as a partnership.

“Enterprise told everybody that we were partners,” Lynn told jurors. “They said it to us. They said it to customers. They said it to investors. They told the whole world.”

ETP suffered damages ranging between $594 million and $1.3 billion, Lynn said, adding that he also planned to ask jurors to award punitive damages.

“We have to prove three things,” Lynn told jurors. “We have to prove that Enterprise and ETP created a partnership, that Enterprise stole the partnership opportunity from ETP with Enbridge’s help and that ETP suffered substantial harm.”

Not so fast, says Beck, who represents Enterprise. Beck said there are 17 separate internal ETP emails written by executives admitting there was no partnership.

“You will not see any partnership agreements because there were none,” Beck told jurors. “There wasn’t a partnership and they knew it. Neither party wanted exclusivity. Even ETP’s own documents refute the claims they are making today.”

Beck points to an April 21, 2011 letter of agreement that uses terms such as “non-binding” and “proposed joint venture” and a separate reimbursement agreement signed six days later stating that “nothing herein shall be deemed to create or constitute a joint venture, a partnership.”

He showed jurors a May 20, 2011 internal ETP memo stating that the company was “awaiting JV formation” and an Aug. 1, 2011 email from ETP Senior Vice President Lee Hanse calling Enterprise a “potential partner.”

“On Aug. 8, ETP deleted the Double E project from its regulatory submission documents,” Beck said. “In ETP’s mind, this project was dead.”

Beck flashed an Aug. 19, 2011 internal ETP memo on the screen for jurors.

“Earlier this year, Enterprise and Energy Transfer Partners agreed to work toward establishing a partnership in order to jointly develop and construct a crude oil pipeline from Cushing to Houston,” the memo read. “Within the past week, after further negotiations, the parties verbally agreed that the proposed project would not be viable and that the parties would not move forward with the project due to a lack of economic justification.”

Beck told jurors that ETP’s out of pocket expenses were only $35,000, while Enterprise’s expenses were $1.7 million.

“This project failed for a very good reason: they couldn’t get enough shippers,” Beck told jurors. “They want you to award hundreds of millions of dollars for a project for which they contributed nothing.”

The first witness in the trial, ETP President and Chief Operating Officer Marshall “Mackie” McCrea, told jurors about being contacted by Enterprise COO Jim Teague, who set up a meeting in Houston on March 31, 2011 to discuss a possible partnership.

McCrea testified that Enterprise officials had the idea of using ETP’s existing Old Ocean Pipeline, which runs from Houston to Dallas, as part of a bigger project to move oil from Cushing to Houston.

He told jurors that Teague and others at Enterprise estimated they could move about 420,000 barrels of oil a day through the pipeline at an estimated annual revenue of $462.9 million. They called the new project Double E.

“It was very exciting,” McCrea testified. “The reason we were so excited about this partnership was that in the pipeline business, it is so important to be the first. Speed to market. It gave us a significant advantage.”

McCrea says ETP and Enterprise signed the April 21 letter of intent but that the relationship almost immediately evolved.

“We quickly moved away from that agreement and toward a full partnership,” he testified. “We were conducting ourselves as partners. It was important for us and Enterprise that we make it clear to our customers that we were a partnership.”

McCrea will return to the witness stand when the trial resumes Monday.

Three Texas Energy Giants Take Multibillion-dollar Dispute to a Jury

By Mark Curriden, JD

Senior Writer for The Texas Lawbook

DALLAS (January 24) – When does a business relationship become a partnership?

That question is at the heart of a multibillion-dollar dispute involving three giant oil and gas companies that are in trial this week in Dallas. Opening statements are scheduled for Thursday.

Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) of Dallas claims that Houston-based Enterprise Products Partners broke its commitment to jointly build a pipeline from Cushing, Okla. to Houston that both companies initially estimated could bring them billions of dollars in revenues annually.

ETP argues that Enterprise and Canadian-based Enbridge conspired to illegally cut ETP out of the deal.

Enterprise and Enbridge, in court documents, say ETP’s lawsuit is “meritless” because there never was an actual partnership or joint venture with ETP.

“Energy Transfer Partners is trying to get in the courthouse what it could not achieve in the marketplace,” lawyers for Enterprise said in court documents asking the judge to dismiss the case.

Dallas County District Judge Emily Tobolowsky denied the request. Jury selection starts Monday with opening statements to the 12-person jury expected Thursday. The trial is expected to last four weeks.

“This is going to be a great case because the issues are important and there are so many great lawyers involved,” says David Elrod, a Dallas trial lawyer whose practice focuses on energy litigation.

The case, which has received very little public attention, pits some of Texas’ most prominent trial lawyers against each other.

Dallas trial lawyer Mike Lynn of Lynn Tillotson Pinker & Cox represents ETP. David Beck of Beck Redden in Houston and Dick Sayles of Sayles Werbner are defending Enterprise. Dallas attorney Jeffrey Levinger and a team from Sullivan & Cromwell in California represent Enbridge.

“Mike and Dick and David are some of the best lawyers practicing law today,” said Elrod.

All of the lawyers declined to comment on the case.

While most business contract disputes are mired in the arduous interpretation of highly technical legal language, this trial is expected to provide extraordinary insight into the business operations and strategic thinking of leaders at three of the largest and fastest growing oil companies in North America.

Top executives at all three energy companies are under subpoena and expected to testify.

But in court documents, the three companies say the primary issue at the heart of the case is whether ETP and Enterprise legally formed a partnership to build the pipeline from Cushing, which is a major oil hub, to Houston, where the crude could be refined or shipped.

ETP says yes. The Dallas-based energy conglomerate, which has about $50 billion in oil and gas assets, claims Enterprise majority owner and chairman Dan Duncan of Houston initially approached ETP about a joint venture in the months before he died in 2010.

Enterprise, which has an estimated $38 billion in assets, and ETP renewed partnership discussions in the spring of 2011 and signed a non-binding agreement a few weeks later.

ETP says the relationship quickly solidified and the partnership started taking shape.

“ETP and Enterprise shared joint control over the partnership’s commercial activities, jointly meeting with potential customers, jointly marketing the partnership to potential customers and jointly making operational decisions,” ETP’s lawyers state in court records.

“The parties unequivocally and repeatedly told potential pipeline customers, regulators and investment banks in formal written materials that they had formed a joint venture and that the parties had agreed to share profits and losses on a 50/50 basis,” ETP claims.

The two companies, which called their new venture Double E Pipeline, even signed a deal in August 2011 with Chesapeake Energy to ship “at least 100,000 barrels of oil per day on the Double E Pipeline for a 10-year period.”

Less than a month later, Enterprise announced it was ending its relationship with ETP to do a similar partnership with Enbridge, a company based in Calgary that has about $30 billion in oil and gas assets and annual revenues of about $11 billion.

ETP claims that Enterprise and Enbridge conspired to interfere with and end the joint venture with ETP, which is seeking more than $1.2 billion in actual and punitive damages.

Enterprise and Enbridge argue there was no actual partnership with ETP because the two sides never took the official steps to finalize the deal and that Enterprise legally backed out of the proposed joint venture.

Enterprise lawyers, in court documents, point to the April 21, 2011 letter between the two companies as proof that their partnership had not been finalized.

“No binding or enforcement obligations shall exist between the parties with respect to the [relationship] unless and until the parties have received their respective boards’ approvals,” the agreement stated.

“The parties made crystal clear that they had not yet agreed to undertake the proposed joint venture,” Enterprise lawyers said in court records. “Despite months of hard work by Enterprise’s employees, Enterprise and ETP were unable to secure sufficient commitments from prospective shippers of crude oil to make the proposed joint venture with ETP commercially viable.”

ETP lawyers, in court documents, say the relationship between the two companies had moved well beyond the terms agreed to in the April 2011 letter.

Lawyers for ETP argue that Texas law liberally defines the existence of a business partnership, even in some cases in which the parties involved claim there is no such partnership, much like the existence of a common law marriage under Texas family law.

© 2014 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.