© 2017 The Texas Lawbook.

By Mark Curriden

(Feb. 23) – Should law clerks for federal judges be allowed to work on cases involving law firms that have previously employed them or plan to employ them in the future?

This legally sensitive issue is at the heart of an attempt to revive a multimillion-dollar breach of contract lawsuit filed by former shareholders of an Irving-based hotel hospitality real estate investment firm against Goldman Sachs Realty Management Group and five of its current and former board members and executives from Texas.

The litigation also raises the question of just how much influence law clerks have on judges when it comes to decision-making.

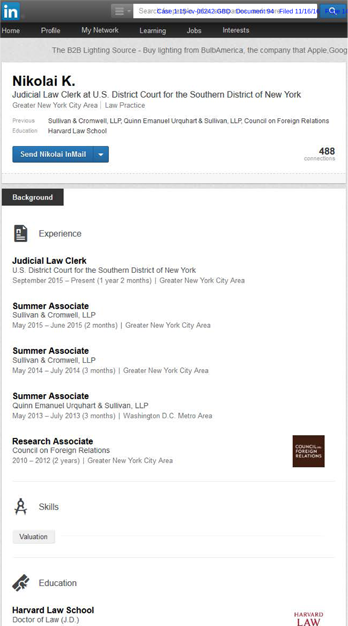

In federal court documents obtained by The Texas Lawbook, the Dallas law firm Gruber Elrod Johansen Hail Shank, which represents the investors, claims that a law clerk for the federal judge who worked on their case was previously employed by the opposition law firm, Sullivan & Cromwell, and had a standing offer to return to Sullivan when his judicial clerkship ended.

Gruber Elrod claims that neither of these potential conflicts of interests was ever disclosed.

Sullivan rejects any accusations of ethical misconduct and says the clerk’s ties to the law firm played no role in the judge’s ruling.

Now, the litigation has become bitterly contentious. Lawyers at Sullivan accuse their legal opponents of “abusive tactics,” improperly “attacking the integrity” of a federal judge and unfairly impugning the reputation of a judicial law clerk.

Gruber Elrod partners claim Sullivan lawyers have reacted to inquiries “with an over-the-top outpouring of venom.”

“Defendants have threatened plaintiffs, stonewalled them, attempted to sanction them, castigated them and now ask that plaintiffs be forbidden from filing with the court,” Gruber Elrod partner Michael Lang wrote in a brief to the federal court in the Southern District of New York. “Plaintiffs are frankly baffled by the litigation conduct of the defendants.”

“Holy crap! How did the lawyers at Sullivan & Cromwell not realize that there is an absolute appearance of a conflict of interest?” says Randy Johnston, a Dallas legal ethics expert who reviewed the court documents in the case at the request of The Texas Lawbook.

“Under the facts as laid out, this law clerk should never have worked on anything involving Sullivan & Cromwell,” says Johnston, a partner at Johnston Tobey Baruch. “We are trusting young, inexperienced law clerks, who still pick their nose and eat their boogers in public, to stand up on their own when conflicts arise. That doesn’t make sense.”

Lawyers at both Gruber Elrod and Sullivan either did not respond to inquiries for comment or declined to discuss the case.

“Sullivan & Cromwell comes across as incredibly defensive, especially for a law firm with such a great reputation for professionalism,” says retired U.S. District Judge Royal Furgeson, who is now the dean of the University of North Texas School of Law.

“We do not know all the facts, but the law firm, out of an abundance of caution, should have disclosed its relationship with the clerk. It certainly raises the appearance of impropriety.”

The plaintiffs, represented by Gruber Elrod, claim they are owed about $20 million as a result of subsequent asset divestitures and transactions in 2014.

Goldman Sachs Realty, which is primarily headquartered in Irving and is a portfolio company of Goldman Sachs in New York, denied that it breached any duties to the former shareholders.

In August 2016, U.S. District Judge George Daniels of the Southern District of New York agreed with the defendants and dismissed the case.

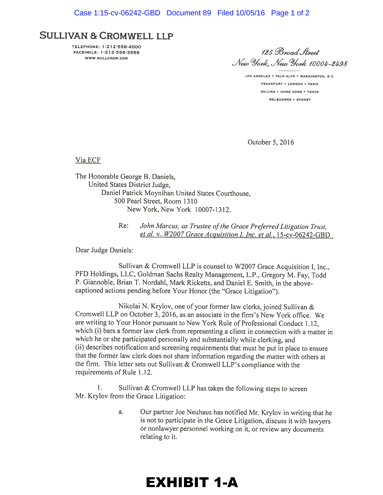

Five weeks later, Wall Street legal powerhouse Sullivan & Cromwell, which represents Goldman Sachs Reality and its officials, sent a letter to Judge Daniels stating that the law firm had hired Nikolai N. Krylov, one of the judge’s law clerks, at the time that the case was being litigated.

In a letter dated Oct. 5, 2016, Sullivan partner Darrell Cafasso wrote that the firm would take “steps to screen Mr. Krylov” from the litigation. He said that the lawyers and legal assistants working on the case had been instructed “not to discuss” the litigation with Krylov and to block him from having access to documents in the case.

Five days later, Gruber Elrod’s Lang responded with a letter to Judge Daniels pointing out that Sullivan & Cromwell had failed to disclose that Krylov had a previous employment history with the law firm.

Lang stated that Krylov worked as a summer associate at Sullivan in 2014 during his second year at Harvard Law School and again in May and June of 2015 – three months before he joined Judge Daniels as a clerk. As evidence, Lang included a copy of Krylov’s LinkedIn page detailing his time at Sullivan.

“Here, while serving as a clerk for Your Honor, Mr. Krylov was personally and substantially involved in the Grace Litigation,” Lang wrote to Judge Daniels on Oct. 10.

“Mr. Krylov’s LinkedIn website discloses that Mr. Krylov previously worked for Sullivan & Cromwell as a summer associate and then began his employment with Sullivan imminently after graduating from law school, in the months preceding his clerkship with Your Honor,” the letter stated.

Lang asked Judge Daniels to force Sullivan to disclose all details about the clerk’s relationship with the law firm and whether the clerk participated in the preparation of the judge’s order dismissing the case.

In a subsequent court petition, Gruber Elrod asked Judge Daniels to recuse himself from the case. The dispute has now been transferred to U.S. District Judge Laura Taylor Swain.

In legal briefs filed with Judge Swain, Gruber Elrod partners argue that “these new facts raise the appearance of partiality” by the court and ask that Judge Daniels’ order dismissing the case be revisited by another judge.

“Public confidence in the integrity of the court system would be significantly damaged by the facts of this case if there is no remedy,” Lang wrote. “Goldman Sachs is one of the most controversial entities in the country, and the appearance that it may purchase access to the chambers along with the expensive services of S&C would only confirm deeply-felt public suspicions of undue influence by certain large financial institutions.”

In response, Sullivan partner Sharon L. Nelles argued in court documents that the Gruber Elrod petition is “baseless.” In addition, Sullivan lawyers asked Judge Swain to order the Gruber Elrod attorneys to stop filing new petitions in the litigation.

“First, there is no reason whatsoever to believe that the law clerk’s employment relationship with defense counsel’s firm before or after his clerkship led to any ‘injustice’ in this case,” Nelles wrote on Jan. 20, 2017.

“To the contrary,” Nelles continued, “Judge Daniels’ decision – which, of course was issued by Judge Daniels, not his law clerk – was thorough and well-reasoned and it followed upon multiple amendments to the pleadings, full briefing by the parties and extensive oral argument.

“Plaintiffs have a documented history of harassing, unsupported and duplicative filings,” Nelles stated. “Plaintiffs attacked the integrity of the court’s decision-making process and impugned a young law clerk just beginning his legal career, unnecessarily naming him in repeated public filings.”

Nelles wrote that the “vexations and abusive tactics” employed by Gruber Elrod partners, “should be brought to an end.”

Gruber Elrod lawyers responded that Sullivan – not Judge Daniels – is to blame.

“It is possible that Judge Daniels may not have known of the conflicts – that he did not know that Krylov had clerked for S&C and planned to return,” Lang wrote. “If so, shame on Krylov and shame on S&C.”

Lang stated that the legal standard is whether a reasonable observer would question the court’s impartiality.

“A reasonable person would know that many law clerks are trusted to advise the court of the merits of a party’s position, suggest rulings and draft opinions,” Lang wrote. “A reasonable person would also object to the defendant’s counsel’s employee filling any of these roles.

“Anything other than a prompt sequestration by the court would leave Krylov in an untenable position,” he stated. “How could he reject his past and future colleagues’ (and supervisors’) legal positions – especially when it could expose an important client like Goldman Sachs to a loss and S&C itself to liability.”

Judge Furgeson, who reviewed the court record in the Goldman Sachs case at the request of The Texas Lawbook, says he was “very impressed” with how the Gruber Elrod lawyers raised the issue involving the judicial clerk’s potential conflict.

“The Gruber folks clearly have an obligation to their client to raise the issue,” Judge Furgeson says. “It is a delicate issue in questioning how a judge interacts with his or her law clerks. In this case, we do not know what the law clerk disclosed to the judge. The judge might not have known anything.”

© 2017 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.