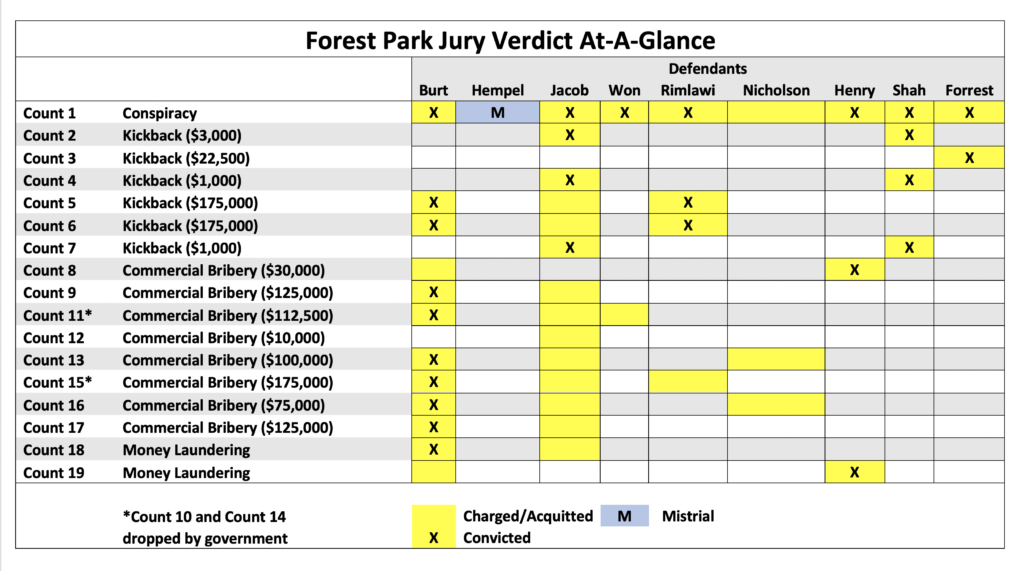

A jury in the Forest Park Medical Center bribery and kickbacks trial returned its verdict late Tuesday, convicting seven of nine defendants on charges ranging from conspiracy to money laundering. One defendant, Dr. Nick Nicholson, was acquitted of all charges. The jury was unable to reach a verdict regarding the one charge against Carli Hempel, the director of bariatric services at the hospital.

Mac Burt, co-administrator at Forest Park, was convicted on 10 of 12 counts.

Dr. Douglas Won, a spine surgeon and the co-founder of the Minimally Invasive Spine Institute, was convicted on one of two counts.

Dr. Michael Rimlawi, Won’s onetime partner at MISI, was convicted on three of four counts.

Dr. Shawn Henry, a Fort Worth back surgeon, was convicted on three of three counts.

Dr. Mike Shah, a pain-management physician, was convicted on four of four charges.

Jackson Jacob, who owned the companies through which Forest Park channeled payments to physicians, was convicted on four of 14 charges against him.

Iris Forrest, a nurse and workers’ comp insurance consultant, was convicted of the two charges against her.

The Forest Park inquiry, alleging a vast bribery and kickback conspiracy involving prominent surgeons and a luxurious physician-owned hospital, has been closely watched by healthcare practitioners – and their counsel – nationwide.

Writing for The Lawbook, Dick Sayles and Wendi Rogaliner of the Bradley firm called it “one of the highest profile health care fraud trials in a generation. … [T]he import is clear: the government means business when it comes to health care fraud and is focused on suspect arrangements in the health care space.”

Following the verdict, that warning was echoed by Erin Nealy Cox, U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Texas: “The verdict in the Forest Park case is a reminder to healthcare practitioners across the District that patients – not payments – should guide decisions about how and where doctors administer treatment. We are grateful to the Forest Park jury, 12 men and women who listened attentively through seven long weeks of trial. It’s obvious from the verdict that they deliberated each charge carefully, and we appreciate their service.”

Sentencing for those defendants found guilty has yet to be scheduled.

Read The Lawbook’s continuous daily coverage of the Forest Park Medical Center trial

Tom Melsheimer, who represented the only defendant acquitted of all charges, said Dr. Nicholson was ecstatic with the outcome.

“We could not be happier. It’s very hard in a criminal case in federal court to be on the right side. Dr. Nicholson and his family are thrilled that the jury reached the right result,” said Melsheimer, managing partner of the Dallas office at Winston & Strawn.

Melsheimer praised the jury, which deliberated for 26 hours over five days.

“The jury paid close attention and weighed the evidence very seriously,” Melsheimer continued. The government counted on the jury not making any distinctions among the defendants. I can’t tell you how much respect I have for the citizens who showed up for seven weeks and did the right thing. Frankly, it’s breathtaking.”

Nicholson, surrounded by family members, showed no reaction to his acquittal. He and his entourage departed quickly from the Earle Cabell Federal Building and Courthouse in downtown Dallas.

He told The Lawbook after the verdict that his acquittal still felt surreal, since he and his family have undergone so much pressure and stress since the December 2016 indictment. He praised Melsheimer and the rest of his Winston & Strawn legal team for fighting for him and believing in him.

As the guilty verdicts were read by U.S. District Judge Sidney Fitzwater, Won, who sat stone-faced through every day of the eight-week trial, bowed his head.

So did Rimlawi, Won’s onetime partner.

Rimlawi, the only doctor to testify in his own defense, was teary-eyed as he, friends and relatives rode the elevator down from the 15th-floor courtroom.

His lawyer, Tom Mesereau of Los Angeles, declined to comment. Rimlawi was overheard to say to Mesereau and others, “I’m in disbelief. I thought we had a good system, a fair system.”

Phillip Hayes, the lawyer for Hempel, the one defendant about whom the jurors could not reach a unanimous verdict, said he awaits the government’s decision on whether to retry his client.

“Do we want to go through another two-month trial?” he said. “That seems like a waste of the government’s resources.”

Throughout the trial, Hayes argued that Hempel, a salaried, mid-level manager at Forest Park, was merely following orders from her superiors in the hospital’s executive chain.

After the verdicts were published, Judge Fitzwater asked the prosecutors if any of the defendants, who have been free pending the outcome of the trial, ought to be held in custody pending sentencing.

“All,” replied Assistant U.S. Attorney Katherine Pfeifle.

She added, “Many of these defendants have significant means, and they have ties to foreign countries.”

Judge Fitzwater ignored Pfeifle’s recommendation, continuing the defendants’ freedom pending sentencing.

The government contended that from early 2009 through 2012, Forest Park Medical Center of Dallas took in $200 million in questionable insurance benefits – “dirty money,” as Pfeifle called it her closing argument – by paying off doctors and others to steer patients to the North Dallas surgical hospital.

The bribes and kickbacks totaled $40 million, according to a 2016 federal indictment. Much of that money, the indictment said, was disguised as monthly consultant fees or “marketing money.”

Twenty-one people, including eight doctors, were indicted. Ten of the 21 cut plea deals and agreed to cooperate with the government. Among them were Forest Park’s two principal founders, Dr. Richard Toussaint, an anesthesiologist, and Dr. Wade Barker, a bariatric (weight-loss) surgeon; and the hospital’s chief administrator, Alan Beauchamp.

Charges against one defendant, a Tyler doctor, were dismissed. A separate trial is pending for another defendant, Royce Bicklein, a San Antonio lawyer who handled workers’ compensation cases.

That left the nine defendants who were tried before U.S. District Judge Jack Zouhary in Dallas.

The trial began with jury selection on Feb. 20. The government called 47 witnesses over the next 17 days; the defense, 20 over six days.

In the government’s opening statement, Assistant U.S. Attorney Andrew Wirmani said the people who ran Forest Park had one overriding objective: “They wanted to make as much money as they possibly could.”

They did so, he said, by recruiting doctors who could bring in well-insured patients in need of high-volume or high-dollar surgeries, principally bariatric or spinal procedures.

The government contended that Forest Park hid the bribes and kickbacks as consulting fees or, more often, through the hospital’s “marketing program.”

Under that program, prosecution witnesses testified, Beauchamp, the Forest Park boss, would send a monthly lump sum, sometimes $1 million, sometimes $1.2 million, to one of defendant Jacob’s companies, along with a list of doctors (or companies associated with them) and amounts to be paid. Jacob would then cut checks to those recipients.

Defense lawyers argued that Forest Park’s marketing payments not only were legal — they were smart business for a small, new hospital trying to crack a market already crowded with far bigger, better-known medical centers.

By underwriting the marketing of doctors who performed surgeries at Forest Park, the defense argument went, Forest Park was, in essence, marketing itself.

That contention was supported by a leading healthcare lawyer called as a defense witness.

William Meier, a Hallett & Perrin shareholder who has represented hundreds of physicians and other healthcare professionals, testified that the Forest Park marketing agreements were legitimate. He knew that, he said, because he wrote the marketing contracts that Nicholson, Won and Rimlawi signed with Forest Park.

Meier said he spent “hundreds of hours” researching, drafting, and revising the agreements, explaining their provisions to the doctors, and consulting with them once the agreements were executed to make sure his clients were in compliance with the law.

“I spent weeks with these gentlemen,” he testified. “They clearly demonstrated their intent to me.”

As an “out-of-network” hospital, one not under contract with major insurance carriers to provide services at fixed, negotiated rates, Forest Park could bill insurance companies much more for surgeries than the amounts that in-network hospitals agree to accept. Sometimes, prosecutors said, Forest Park’s surgery bills would be three or four times the amount an in-network hospital would charge.

For that very reason, not all insurers provide out-of-network benefits. And policies that do allow patients to go out of network seek to discourage the practice by requiring those patients to pay significantly more for their share of services than they would pay in-network.

This would, under normal circumstances, provide a powerful disincentive to any patient’s agreeing to have surgery at Forest Park – it would cost them a ton of money. Forest Park, witnesses testified, got around this with a nod and a wink: Patients were told the hospital wouldn’t charge them any more than what their co-payments would have been at an in-network facility; and, sometimes, Forest Park made no attempt to collect even that lower co-pay.

Prosecutors introduced as exhibits billing records from Forest Park with notations that many patients’ bills were being waived or reduced “per Carli” – defendant Carli Hempel.

Beauchamp, testifying for the government, said he made it perfectly clear to the defendant doctors when he recruited them to Forest Park that what he was proposing was “buying surgeries,” a practice he, they, and every medical professional knew was against the law.

The marketing contracts, he said, were just a means to disguise the payoffs.

“We papered it up to make it look good,” he said.

“Marketing money,” he testified, only went to doctors who agreed to perform surgeries at Forest Park or refer patients there or both. Beauchamp said he closely monitored the numbers of patients each doctor sent his way; those who underperformed saw their monthly payoffs reduced or cut off, he said.

“If I was paying for their surgeries,” he said, “I wanted to make sure I was getting a return.”

Barker, Forest Park’s co-founder, testified that he was both a payor and a payee of bribes. He took $100,000 to $125,000 a month from his own hospital in exchange for performing surgeries there, he said. And he helped recruit other doctors into the scheme. He also testified that Burt, the Forest Park administrator on trial, was in on the conspiracy.

David Kim testified for the government that he knew Forest Park was bribing doctors, because Forest Park was bribing him. Kim, who has surrendered his medical license, used to be a bariatric surgeon.

“I accepted money in exchange for patients, sending patients to Forest Park,” he testified, adding, “And I cheated on my taxes.”

Under his deal with the government, Kim pleaded guilty to one count in the Forest Park indictment, soliciting or receiving illegal remuneration, and to a separate charge of filing false income tax returns. On cross-examination, he said he’d failed to report $18 million in income.

He relinquished his medical license in 2017, he said, because “after long and painful consideration, and long soul-searching, I felt that I no longer deserved to practice medicine. … I dishonored my profession.” (On cross, however, he acknowledged that his conscientious gesture was hollow: the Texas Medical Board would have yanked his license anyway, once he pleaded guilty to two federal felonies.)

Kim, who said he was a friend of defendant Nicholson’s, recounted a conversation with Beauchamp in which the Forest Park executive voiced his displeasure that Nicholson wasn’t sending more surgeries the hospital’s way. Nicholson was being paid at least $70,000 a month in “marketing money.”

“Hey, your buddy Nicholson, he needs to bring more cases to the hospital if he wants his marketing checks,” Kim recalled Beauchamp’s telling him.

Kim said he relayed the message to Nicholson, advising him to pick up the pace. “If you can’t bring a weight-loss surgery, bring gall bladders – something.”

Nicholson’s reply, Kim said, was “I understand and I will.”

Among the nine defendants on trial, only one doctor, Rimlawi, testified in his own behalf.

“I’m totally confused sometimes why I’m even here,” he said, adding, “I never took a kickback or a bribe.”

Rimlawi said he had no inkling that there was anything improper about his accepting monthly payments of $100,000 or more from Forest Park to cover the advertising costs of his medical practice.

“I never for one second thought that it was illegal. Not for a second,” he said.

He accused the government of pressuring and scaring witnesses, coercing people to concoct false accusations against him, and “ruining my reputation in the community” by getting in touch with his former patients and telling them “Dr. Rimlawi took bribes and kickbacks.”

“I’m not guilty,” he said. “I did not do this stuff. I feel like they’re twisting facts.”

The Forest Park case was originally assigned to Judge Fitzwater. He relinquished it when, in 2017, he was dispatched to Amarillo (like Dallas, part of the Northern District of Texas) to help alleviate a backlog of federal criminal cases there.

Zouhary, from the Northern District of Ohio, was brought to Dallas as a visiting judge to oversee Forest Park.

In her closing argument, Pfeifle, the prosecutor, said the physicians snared in the Forest Park investigation did more than take bribes and cheat giant insurance companies: They betrayed the trust of their patients.

Pfeifle said “we as patients deserve to know” that our doctors are making treatment decisions based on what’s in our best interest – not on whether a corrupt hospital is slipping them checks.

Several patients of the defendants, she noted, testified that they were given no choice when their surgeries were scheduled at Forest Park.

“They deserved to know that their surgeries were motivated by money,” she said. “And none of these doctors ever told them that.”