© 2017 The Texas Lawbook.

By James Chenoweth and David Sinak of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher

(Dec. 21) – The U.S. House and Senate passed the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (the “Act”) on Wednesday, reflecting the combined agreement of Republicans in the two bodies settled in conference. It has been 31 years since Congress last achieved such a comprehensive tax reform passage.

Houston, we have new tax rates.

$100 × 21% = $21 corporate taxes

$79 after tax corporate earnings × (20.0% + 3.8%) = $18.80 shareholder taxes

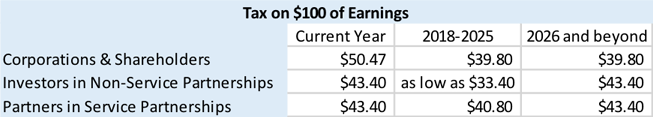

The following table illustrates the highest effective tax rates imposed on taxpayers under the Act.

For pass-through earnings, such as income from a K-1 earned by investors in a private equity investment or a master limited partnership (“MLP”) or income from an S corporation or sole proprietorship, the Act applies the Senate Bill’s approach of allowing up to a 20 percent deduction for items of net income from each qualified trade or business of the taxpayer, subject to certain restrictions. Assuming the deduction applies in full, the federal government will yield $33.40 from every $100 of pass-through earnings through 2025.

($100 – $20) × 37% + ($100 × 3.8%) = $33.40 taxes on pass-through earnings through 2025

Except in a few cases, the Act limits this trade or business deduction to the greater of (i) 50 percent of the taxpayer’s share of W-2 wages paid by the company and attributable to a trade or business and (ii) the sum of 25 percent of the taxpayer’s share of such W-2 wages and 2.5 percent of the initial tax basis of all ‘qualified property’. Qualified property for this purpose is generally tangible personal property subject to depreciation during its depreciable life, or, if longer, during the first 10 year period after the taxpayer places the property in service.

Importantly for the midstream sector in particular, the Act allows income from MLPs to qualify for the 20% deduction without regard to this W-2 limitation, thanks to an amendment by Senator Cornyn of Texas.

Where the W-2 limitation applies, there is an incentive for vertical integration, as pass-through companies who have high 1099 expenses and low W-2 wages seek to lower their cost of capital by raising their W-2 expenses. In this sense, the Act promotes consolidation.

As both the House and Senate Bills exempted from favorable treatment traditional service industries, such as banking, financial services, brokerage services, accounting and law, it was no surprise that the Act generally does not allow a pass-through deduction for taxpayers in those industries (although engineering was spared). Service providers in these service fields may benefit from the pass-through income deduction to the extent their income is not greater than $315,000 in the case of married taxpayers filing jointly, with the benefit phasing out for such taxpayers with income between $315,000 and $415,000. In the case of a single return, the income thresholds are 50 percent of those that apply in the case of the joint return.

The Act makes clear that the trade or business deduction applies regardless of whether the taxpayer itemizes, so an MLP unitholder who takes the standard deduction will still be able to enjoy the benefit of the 20 percent deduction.

By now, readers are wondering what the Act means for investors in high state tax jurisdictions, given the new and widely reported limitation on state tax deductions to $10,000. The reduction in the highest individual tax rate from 39.6 percent to 37.0 percent mitigates the pain of losing state tax deductions to some degree, but only up to about a 6.5 percent state income tax ($93.5 × 39.6% is approximately the same as $37 tax on $100).

Because of this net detriment to taxpayers in high tax jurisdictions, private equity and others looking for investors might find individuals in lower tax jurisdictions (e.g., Texas, Florida) with more disposable income as estimated tax payments begin to be made in 2018.

Five Years of Tax Deferred Capital Expensing.

The immediate expensing of investment is one of the items that went through the GOP’s Framework for Tax Reform, the House Bill, the Senate Bill and the Conference Committee Bill mostly untouched. An immediate deduction will be available for investments in property, plant and equipment from the period beginning September 27, 2017 to December 31, 2022. (Following 2022, the 100 percent depreciation deduction phases out in 20 percent increments every year until no deduction is allowed on general qualified property beginning in 2027.)

As was done in each of the House and Senate Bills, the Conference Committee Bill doubles the existing 50% “bonus depreciation” deduction to 100 percent for property with a depreciable recovery life of not more than 20 years.

It is important to remember that immediate expensing of these capital expenditures results in a deferral (and not elimination) of tax; the day of reckoning will come upon the ultimate taxable disposition of the property.

Imagine sitting in a conference room while C suite executives discuss using $100 of earnings to either (i) pay a $21 tax at the corporate level and use the remaining $79 to repay debt or make a distribution to shareholders, or (ii) buy a $100 asset and pay no taxes this year. It is easy to see how this 100 percent deduction provides an incentive to grow for midstream and downstream companies that is hard to overstate.

Importantly, the Act allows the 100% deduction for capital expenditures used to acquire pre-existing (that is, used) property from unrelated persons. In the current oil and gas environment, where companies are shedding non-core assets, the 100% bonus depreciation regime provides an extra incentive for buyers of such assets to close deals in the next 5 years.

R.I.P. Corporate AMT

The Act completely eliminates the corporate AMT. This repeal will result in a tax cut for a number of oil and gas companies, which often get picked up under the AMT due to the large availability of deductions in the sector that are tax preferences under the AMT (e.g., IDCs, percentage depletion, and accelerated depreciation).

The Act also increases the exemption amounts for the individual AMT for the 2018-2025 tax years, consistent with the Senate Bill’s proposal.

Planning Opportunities

Net operating losses (NOLs) arising in years after 2017 will only be useable up to 80% of a taxpayer’s net income. The Act grandfathers NOLs arising in 2017 and prior, which can be carried forward and used without being subject to the 80 percent limit.

With the absence of an AMT in 2018, an oil and gas company can accelerate deductions with abandon, but companies will want to manage drilling schedules and deduction timing to maximize tax benefits. With the limit on NOLs to 80% of taxable income, stockpiling NOLs will no longer have the benefit that it has in the past. Beginning in 2018, timing deductions to coincide with taxable income will be a far better tax planning strategy.

Necessitates Review of JV Agreements

At the risk of ending this article on a hyper-technical note, the Act repeals a rule in the tax code that terminates a partnership for tax purposes upon the sale or exchange of a partnership interest of 50% or more of the capital and profits interests in the partnership (when aggregated with all other sales and exchanges in a 12-month period). The termination rule causes administrative burdens (e.g., short tax year return filing, necessitates new tax elections) as well as a deferral of depreciation deductions.

Many JV agreements in the midstream and downstream sectors (e.g., pipelines and LNG joint ventures) either outright prohibit transfers that would trigger this technical rule or require the transferor to indemnify the other JV participants in the event of certain transfers. Depending on how the agreement is worded, there could be instances where language unnecessarily limits a transfer. JV Participants will want legal counsel to review agreements to ensure that any problematic transfer restriction language is amended.

James Chenoweth is a partner in the Houston office of Gibson Dunn. David Sinak is a partner in the firm’s Dallas office. Eric Sloan, a Gibson Dunn partner in New York, contributed to this article.

© 2017 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.