© 2013 The Texas Lawbook.

By Natalie Posgate

Staff Writer for The Texas Lawbook

(July 8) – The juris doctorate has been viewed for decades as a nearly automatic ticket to success and wealth, even in tough economic times.

But times have changed and law schools are witnessing a dramatic decline in enrollment.

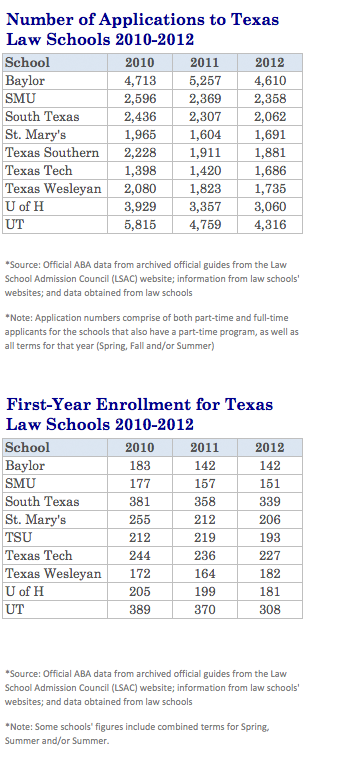

Texas’ nine law schools – facing a difficult job market for graduates and ballooning tuition costs – have seen their combined incoming first year classes drop by more than 10 percent during the past two years, according to statistics compiled by the Law School Admissions Council.

The trend is expected to continue. LSAC confirms that, as of June 28, applications for the upcoming fall term were down 18 percent nationwide from a year earlier. Nearly all Texas law schools said they have seen their applications for the fall 2013 term drop by 12 percent from 2012.

Eight of the nine law schools in Texas had smaller enrollment in 2012 than in 2010.

The University of Texas School of Law had 21 percent fewer first year students in 2012 compared to two years earlier. It has seen a 26 percent decline in applications.

The SMU Dedman School of Law saw its first year law class drop 15 percent and applications fall more than nine percent from 2010 to 2012.

The trend is not isolated to Texas. LSAC reports that law school applications are at a three decade low, down nationally about 38 percent since 2010 and down nearly 50 percent from 2004.

“Legal education is facing a critical time and some big decisions,” said long-time legal educator and former Texas Tech University School of Law Dean Frank Newton. “The law degree is not the fall back guarantee that it used to be.“

Newton, who has been one of the most widely respected leaders in legal education in Texas for decades, says business schools and engineering schools experienced periodic bubbles over time, but that law schools have avoided it until now.

Newton and others say that law schools expanded their class sizes during the past decade in response to market demands, which saw top tier Texas law firms increase starting salaries for new law graduates from $75,000 in 1999 to $160,000 in 2008 and profits per partner regularly exceed $1 million.

At the same time, law schools promoted their job placement rates at 95 percent or higher, even during the recessionary years of 2008, 2009 and 2010.

As a result, law school applications exploded to record levels and law schools expanded their enrollment to meet the demand.

The cost of legal education also skyrocketed during the past dozen years. The average tuition cost at Texas law schools – public and private – has doubled since 2001, according to the American Bar Association.

Then, in 2010, tough economic times finally caught up with law firms, which significantly cut back hiring new law school graduates at exactly the time that the increased third year law students were graduating and hitting the job market.

The ABA reports that only two-thirds of 2012 Texas law school graduates had found full-time jobs as lawyers nine months after graduation; another 12 percent found non-lawyer professional jobs. Nearly 10 percent of those Texas law school graduates had not found a job of any type after nine months.

“Law students saw this elevator that kept going up, offering near guaranteed jobs paying six-digits in good economic times and bad, so they jumped on board,” Newton said. “Suddenly, the elevator isn’t going up as high, graduates cannot find jobs and they cannot repay the $100,000 in student loans.”

Most legal educators agree that the poor job placement numbers have suppressed interest in law school as an option for career advancement.

“Prospective students may be responding to perceived difficulties in available law careers by deciding not to apply to law school,” said Nicole Neeley, assistant dean of admissions at Baylor Law School.

Officials with UT Law School, the state’s largest public law school, refused to comment. The Texas Lawbook called and messaged a cell phone number posted on the UT Law School’s Student Bar Association listed as the organization’s contact. Someone with that cell phone, which is still listed as the contact number, responded with a two-word profane text message.

Baylor Law School’s first year class dropped 22 percent during the past two years, but its applications for the upcoming fall term are expected to be down only 12 to 14 percent, according to Neeley.

The decline in applications means Texas law school recruiters find themselves going head-to-head for the best students.

“It’s definitely correct to say that the competition is increasing and becoming fierce but we hopefully will more than hold our own when it comes to competition for the better students,” said Richard Alderman, the interim dean at the University of Houston Law Center.

Stephen Perez, the assistant dean for admissions & recruitment at Texas Tech School of Law, believes law school applicants have become savvier by pitting the law schools against each other, which is putting extra pressure on the law schools to match one another’s offers on factors such as scholarships.

“Students know they are in the driver’s seat right now and it’s a down market,” he said. “They have more information than they’ve had before. Students now are shopping around a little more. That’s the pressure that’s on schools.”

According to Perez, the smaller application numbers can cause schools to accept people they would normally deny. He compared the phenomenon to a food chain.

“People at UT will take some they usually don’t take and then affect others,” he said. “SMU goes down the chain and the pie is shrinking. If I want my slice to stay the same size, I have to take it from somebody else.”

Former SMU Dedman School of Law Dean John Attanasio believes that many of the problems law schools are facing today are due to self-inflicted wounds.

“I think inadequate transparency has exacerbated the problem,” he said. “Had we been more transparent about what the opportunities are and are not, some of the paranoia and even hysteria that existed for a while about going to law school would not have existed.”

At the end of the day, according to Newton, law schools in Texas continue to offer “too many seats” at too high of a cost for such a dramatically changing legal market place.

Newton and others say the legal market place has segmented into two groups. The first group is an ever-shrinking group of elite lawyers and firms working on high-dollar business matters and earning big bucks. The second group are rank-and-file lawyers who are seeing their paying client base disappear because potential clients can no longer afford even the least expensive legal counsel or because more and more clients are opting to handle legal matters ranging from wills, estates and divorces on their own using self-help legal forms offered on the Internet or by the courts.

“For decades and decades, law schools have gotten good at doing more with more – they know no other way,” he said. “My bet is that most Texas law schools will muddle along thinking that things will get better, but they will eventually be forced to change. The law school that changes first will be viewed as visionary.”

© 2013 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.