The list is growing: J.C. Penney; Neiman Marcus; Golds Gym; Diamond Offshore Drilling; Dean Foods; Alta Petroleum; TriPoint Oilfield Services; Sheridan Holding; Pier 1; and Stage Stores.

More Texas businesses are filing for bankruptcy this year than during the Great Recession or anytime in the past two decades, and legal experts say the wave of insolvencies and restructurings is still far from breaking or hitting their peak.

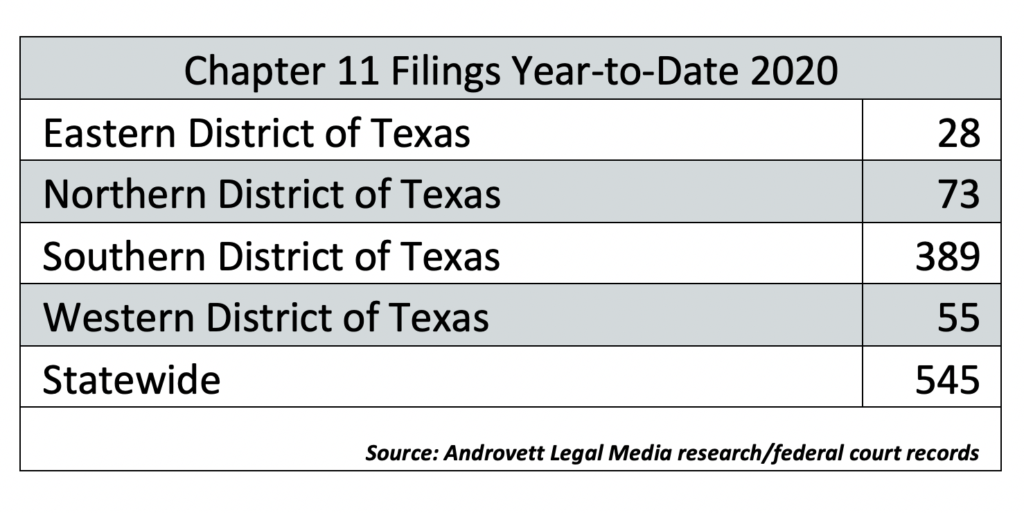

Between Jan. 1 and May 5, more than 545 Texas companies have filed for protection from creditors under Chapter 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code – up from 234 such filings during the same period in 2019, or a 133% jump, according to new data provided exclusively to The Texas Lawbook by Androvett Legal Media research.

The data shows that U.S. Bankruptcy courts in the Southern District of Texas – specifically Houston – are the epicenter for the historic number of corporate restructurings expected to be filed this year. So far in 2020, five times more business bankruptcies have been filed in Houston than in any of the other three federal district courts in the state.

A distant second is the Northern District of Texas, which is expected to announce a new bankruptcy judge in the next few weeks. Veteran restructuring lawyer Michelle Larson, a partner at Carrington Coleman, is expected to get the position.

Corporate bankruptcy experts overwhelmingly agree that the COVID-19 and oil price crises are causing a flood of restructurings and liquidations in the retail, hospitality, healthcare and energy sectors.

There are a handful of corporate law firms who have beefed up their bankruptcy practices during the past several months in order to be positioned to benefit significantly from the crisis by representing debtors and creditors, according to legal industry analysts.

“There is a tsunami coming,” said Foley bankruptcy partner Holly O’Neil. “For tens of thousands of retailers and restaurants and other businesses, their incoming revenue completely stopped, but their expenses kept coming. The options for many of these businesses are running out.”

“A wave of restructuring and liquidations is coming,” O’Neil said.

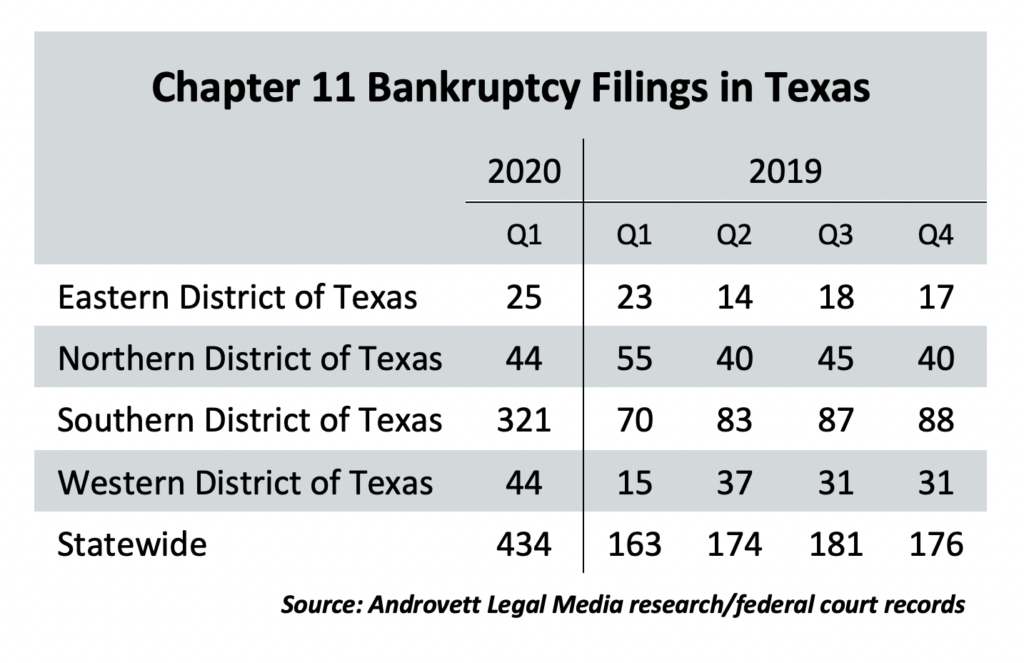

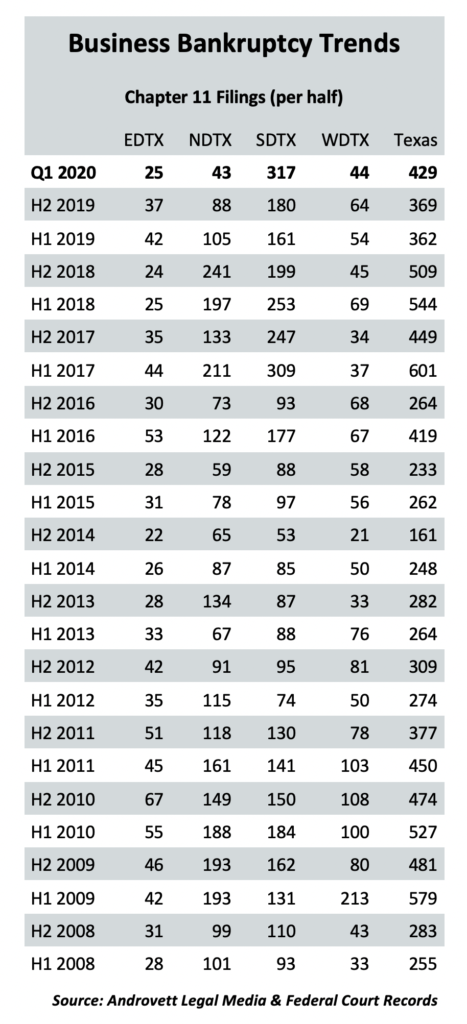

The Androvett data provided to The Texas Lawbook data shows that an average of 32 Texas companies filed each week this year to restructure, compared to an average of 13 companies a week last year and 23 corporate bankruptcies each week in the first half of 2017, which was the previous all-time high in the state.

Several of the new cases include multiple subsidiaries, which count as individual filings and can artificially increase the total bankruptcy case count. For example, Dallas luxury retailer Neiman Marcus filed to restructure under Chapter 11 two weeks ago in Houston. Twenty-three Neiman subsidiaries also filed, including NEMA Beverage Corporation, NMG Salon Holdings and NM Financial Services. Those will be handled as one case even though they are two-dozen separate filings.

Legal experts are quick to point out that those kinds of multiple party debtor cases are filed routinely. A year ago, a Dallas healthcare company with 35 affiliated businesses went to court to reorganize.

“If you are a restructuring lawyer, you are going to be very busy,” said Lou Strubeck, head of the bankruptcy and restructuring practice at Norton Rose Fulbright in Dallas. “Oil and gas and the retail sector had a whole lot of stress even before COVID-19. The only surprising thing is that we haven’t seen the explosion of bankruptcy filings already. But they are still coming.”

Several other prominent Texas companies – including CEC Entertainment and Chesapeake Energy – are reportedly preparing bankruptcy filings.

“I expect the volume will go up significantly. We are in the early stages,” said Duston McFaul, a partner at Sidley Austin in Houston. “This has the makings to be a long, several-year cyclewith widespread imbalances to address.”

‘Pray and Delay’ or ‘Amend and Pretend’

Judy Ross, a partner at the Dallas bankruptcy boutique Ross & Smith, said the large corporate restructurings get the news headlines, but that the crisis is going to have an even larger impact on small-to-midsized businesses that don’t have as much access to the capital markets.

“Retailers and those in the hospitality industry are getting killed financially,” Ross said. “Unless you are Amazon or the maker of toilet paper, your business is in distress. Smaller businesses should try to restructure out of court because bankruptcies are very expensive. For many small businesses, they cannot afford counsel, so they just shut down.”

O’Neil said the “federal stimulus efforts probably delayed many businesses having to file for bankruptcy, but it was just forestalling the inevitable.”

The surge of bankruptcies by small business owners also has been delayed because the stay-at-home orders have prevented owners from finding and meeting with lawyers to handle their filings.

Creditors are being patient with retailers and restaurants, at least for a short time, according to McFaul.

“Lessors are not rushing to push out distressed businesses because there’scurrently no onelined up to replacetenants,” McFaul said.“A strained revenue stream is better than none at all.”

The same is true in the oil industry, only energy company restructurings tend to be significantly more complicated because there are so many parties and because the price of oil continues to be unstable.

Strubeck, who also represents a party in the Boy Scouts bankruptcy case, said “lenders aren’t going to be too aggressive” in forcing energy companies into court to reorganize because “they don’t know what they would do with the assets and they don’t want to run these companies.”

“This cycle we have entered is far from over. We are only seeing the start, and there are a lot of restructurings in the pipeline,” said Vinson & Elkins partner Bill Wallander. “There are upstream companies that are surviving solely because of hedges. Many are facing cash-flow issues. The midstream companies become infected because there is less [oil] to move.”

“The big question is, will private equity jump in or are they gun shy about oil and gas?” Wallander said.

Matthew Cavenaugh, a bankruptcy partner with Jackson Walker in Houston, said the answer to that question is a reason why courts may have seen fewer prepackaged bankruptcies and more “free fall” bankruptcies.

“In 2015 and 2016, there was a lot of capital waiting to invest, which was important for exiting bankruptcy,” he said. “Right now, there’s not a lot of access to capital.”

Cavenaugh said there is another underlying factor that needs to be considered.

“There’s been so much money pumped into the system by the feds,” he said. “There’s no way to know the impact.”

The critical issue for most of these companies is cash – a problem that has been magnified because of the semi-annual determination of borrowing base or the value of the oil still in the ground, which plummeted in April and May.

“Do they have liquidity? That’s the biggest issue,” said Ronit Berkovich, a partner at Weil, Gotshal & Manges. “Only so much can be done through budget cuts. Banks are being flexible right now, but they will only do so to a point … until it becomes too risky.”

As a result of the lowered borrowing base, the practice known as “extend and pretend” – banks ignoring debt problems and just extending existing loans – has given way to a modified version called “pray and delay” or “amend and pretend,” Berkovich said.

Banks are praying the price of crude goes back up.

McFaul said COVID-19 only exacerbated preexisting financial problems in the oil patch.

“The over-supply problem and then the demand shock due to the shutdown has caused cash flow and projections to be hit hard,” he said. “[The] supply side was already out of whack and then demand plummeted. It has been the perfect storm of challenges.”

New Bankruptcy Capitol: Houston

A more recent and warmly welcomed bankruptcy trend regards venue.

For two decades, large Texas corporations – from Enron and Dynegy to American Airlines, Radio Shack and Energy Future Holdings – chose to file their petitions to restructure in the bankruptcy courts in the Southern District of New York or Delaware instead of in Texas.

Former American Airlines General Counsel Gary Kennedy told The Texas Lawbook that he felt pressured by bankers and lawyers to file for Chapter 11 in Manhattan, where the bankruptcy judges had more experience with complex reorganizations.

As these large restructurings left Texas, so did the tens-of-millions of dollars paid to legal and financial advisors in each bankruptcy – a fact that irked scores of Texas lawyers who saw their revenues going to competitors in New York and Delaware.

But then a major shift took place in the spring of 2016 when Chief Bankruptcy Judge David Jones of the Southern District of Texas issued a standing order that directed all complex corporate restructurings to be divided between himself and Judge Marvin Isgur. The order also provided for expedited procedures and 24/7 access to bankruptcy court personnel.

“When you file in Houston, you know the bankruptcy judges that will be assigned the cases, and that offers predictability to clients and their counsel,” said Porter Hedges partner Josh Wolfshohl. “Judge Jones and Judge Isgur were corporate bankruptcy practitioners. They have a very good understanding of what capital structures are like.”

“In Delaware, you don’t know which judge you are going to get,” he said.

The data shows the new standing order has had an impact.

Between 2008 and 2015, the bankruptcy judges in the Northern District of Texas actually handled more business bankruptcies than their colleagues in the Southern District. Over the past four years, however, the two Houston judges have handled 30% more restructurings than their North Texas counterparts.

The gap grew much wider during the first four months of 2020.

So far this year, more than 389 businesses filed for Chapter 11 in the Southern District, which is more than five times the 73 restructurings submitted in the Northern District. In fact, it is 71% of all the corporate bankruptcies filed in Texas between Jan. 1 and May 5.

“Delaware is not as popular as it used to be because there are too many judges there now and less predictability,” Strubech said. “Houston is the safer gamble. Houston now has as many or more complex corporate bankruptcies than any jurisdiction in the country.”

The bankruptcy courts in the Northern District of Texas have seen a small increase during the past six weeks. Court leaders are expected to announce that Michelle Larson has been chosen as the district’s new bankruptcy judge. Larson practiced law at Andrews Kurth for nearly seven years and at corporate restructuring powerhouse Weil, Gotshal & Manges for nearly nine years, where she was involved in representing the Texas Rangers in its 2010 restructuring and sale. She’s been a partner at Carrington Coleman for two and a half years.

Another contributing factor for the increase in Texas bankruptcies, especially among smaller companies, is that the stigma of failure that goes with declaring bankruptcy has faded significantly in recent years.

Multiple bankruptcy lawyers in the small to midsized business space say clients have pointed to President Trump who, prior to becoming president, filed for bankruptcy six times for his hotels and casinos between 1991 and 2009.

The fact that pro-business, fiscal conservatives cited President Trump as a successful business leader as a key reason they voted for him, lawyers said, is evidence that heavy debt and bankruptcy is no longer a dark shadow.

But all the bankruptcy experts agree on one thing:

“The longer the crisis lasts, the deeper the impact,” said Weil partner Kelly DiBlasi. “We are going to see a surge of restructurings in a lot of different business sectors.”

Editor’s Note: Coming later this week, The Texas Lawbook plans to publish an article that examines the law firms in Texas that are best positioned to handle the increase in corporate bankruptcies.