San Angelo litigator Carmen Dusek has been in a reflective mood this spring. It was 10 years ago that she found herself in the middle of the media and legal firestorm surrounding the largest child custody case in Texas history.

Dusek, senior counsel at Jackson Walker, led an intense effort to recruit lawyers from around Texas to represent the more than 400 children who had been removed from a secretive polygamous compound in West Texas.

She remembers throwing sheets over PVC pipe for makeshift cubicles in the city coliseum, so the visiting lawyers could have some privacy with their clients. She remembers an imposing man who helped run the sect pacing the side aisle of a crowded courtroom in a thinly-veiled effort to intimidate women on the witness stand.

But her most vivid recollections are of the children. Girls and young women dressed in full-length pastel dresses, their long hair woven into a single braid. Boys clad in home-sewn shirts and trousers who preferred physical labor to tossing a ball. One weary teenage mother, holding a baby in her arms and learning that a pregnancy test had come back positive.

It was the largest child custody case in Texas history, and Dusek’s involvement is a source both of pride and disappointment.

She is proud of many things – how lawyers answered the call for help, how the matrons of her city fed and housed the visiting lawyers. She doesn’t regret the long hours spent training lawyers on the intricacies of the Texas Family Code and her personal efforts to explain those laws to children who viewed the outside world with suspicion.

But frustration surfaces when Dusek remembers the rulings from Texas appellate courts that ordered the children returned to their parents. The decisions came as Dusek and others were just learning of extensive sexual crimes at the Yearning for Zion Ranch near Eldorado.

“I’m extraordinarily proud to have worked on this case,” says Dusek. “I also have a fondness for many of the girls I worked with and represented. I repeatedly told them, ‘Keep my card. If you ever need anything, I’m only a phone call away.’ That promise still stands today.”

She devours the media coverage that has come with the case’s anniversary and is heartened that many youth have left the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Several have told reporters that the experience with outsiders during the custody cases opened their eyes to kindness from strangers.

They, along with the nation, had watched as FLDS leader Warren Jeffs was captured and sentenced to life in prison for raping two girls, ages 12 and 15. The sprawling 1,700-acre property with the imposing white temple now sits vacant, its upkeep a drain on Schleicher County.

Meeting the Children

Dusek, now 47, was practicing law with her father Clint Symes a decade ago when word first came in early April 2008 of the raid on the YFZ Ranch, about a half-hour drive from San Angelo. The 1996 graduate of Texas Tech University School of Law had clerked at the Third Court of Appeals in Austin and worked early in her career at Jackson Walker. She had returned to her hometown in 2000 and continued to gain experience with complex litigation.

State District Judge Barbara Walther initially appointed Dusek to represent the first 25 girls who were seized from the compound because they were either pregnant or had children. Once the state began to remove young boys, the judge tapped Randy Stout as to help Dusek. Both lawyers had been willing to reduce their fees to handle Child Protective Services appointments.

But nothing could have prepared them for the hundreds of children who would be removed from the ranch over the next few days. They were brought by bus to Fort Concho, a national historic site, and one of the few places in San Angelo with enough space to house the women and children. They were soon moved to the city’s events center and later to group homes around the state.

Dusek and Stout spent long days coordinating with state employees and child advocacy groups. Health screenings began, but not soon enough to prevent an outbreak of chicken pox.

Initially, the lawyers met with the children in large groups, trying to explain their rights and answer questions.

Dusek remembers telling a group of young mothers that each of them would be assigned a personal lawyer for the upcoming court hearing. She asked if there was anything she could tell the lawyers that would help their clients feel more comfortable.

A 16-year-old girl glanced indignantly at Dusek’s blouse, which had elbow-length sleeves, and said, “Less skin. That’s entirely too much.”

“It was a funny moment as I thought to myself, ‘This one is sassy. I like her.’”

A Devastating Ruling

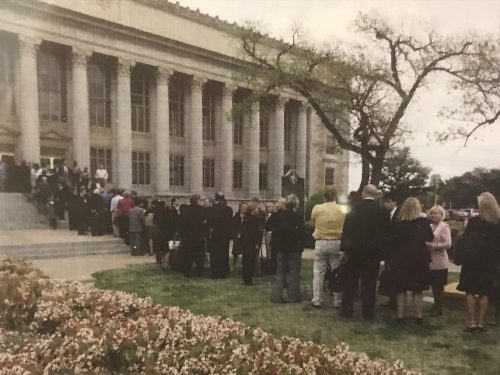

A photo from a plaque hanging on Dusek’s wall shows her and Stout in the middle of a long line of lawyers waiting to get into the courthouse. It was a moment of professional pride to see about 260 attorneys, including many women, step up to represent the children.

“Lawyers called me and said, ‘I don’t have a copy of the Family Code because I’m a real estate attorney but if you need me, I’ll help,’ Dusek says. “We tried to make sure all the children were protected and safe, and most importantly, that they were well represented.”

From the initial outcry by a purported victim that soon turned out to be a hoax call, nothing about the case was simple.

“From a legal perspective, this case was in many ways like a class action or mass tort because there were hundreds of individuals, all with their own needs. Except in this case, we had less than 10 days to get organized.”

Walther’s decision to grant the state temporary custody was challenged in a mandamus petition filed by 38 mothers of 124 children. As the appeal was being played out, the children were placed in residential facilities around Texas.

“The next two weeks after the 14-day hearing were almost as stressful, crazy and chaotic as the first two weeks because CPS started moving kids. They didn’t tell the lawyers, who were infuriated,” says Dusek.

To support its removal of all the children, the state said the group’s practice of marrying young teen girls to older men put all female children at risk of sexual abuse — and male children at risk of becoming adult abusers. CPS officials said they needed to separate the children from their mothers to break a code of silence.

About six weeks after the first children were removed, Austin’s Third Court of Appeals rejected the state’s argument.

“Evidence that children raised in this particular environment may someday have their physical health and safety threatened is not evidence that the danger is imminent enough to warrant invoking the extreme measure of immediate removal prior to full litigation of the issue,” the court said.

On May 29, the Texas Supreme Court agreed. Three justices dissented to returning those girls who had reached puberty.

Family law experts said the state’s mistake was treating the massive removal as if it were a routine case and failing to take a more nuanced approach. Some observers faulted the attorney general, Greg Abbott, for not joining forces with CPS lawyers to defend the case at the Supreme Court.

Dusek was devastated by news.

“Certainly there were some kids who I recognized – 45 days in – probably there aren’t facts to support their continuing to be removed,” she says. “But I had met with exhausted young mothers pregnant with another child and I knew what they were walking back into. And so we worried.”

Following the convictions of Jeffs and 11 other men, the FLDS fractured. Remaining members left Texas for their traditional communities on the Arizona-Utah border.

In the intervening years, Dusek has handled a broad range of litigation. She successfully represented Texas Farm Bureau Insurance in litigation decided in the Eastland Court of Appeals. She won a take-nothing verdict in a $5 million wrongful death case for a rancher sued over an ATV accident.

And although she admits that the FLDS case “burned me out on CPS,” Dusek still takes occasional appointments as a service to the West Texas legal system.