Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton faces the possibility of joining an exclusive club — becoming the third elected official in Texas history to be ousted from office through impeachment — if he is convicted by the Texas Senate in a trial later this year.

Since Reconstruction, the Texas House of Representatives has impeached four other state officials. Two were convicted. The Senate acquitted the other two.

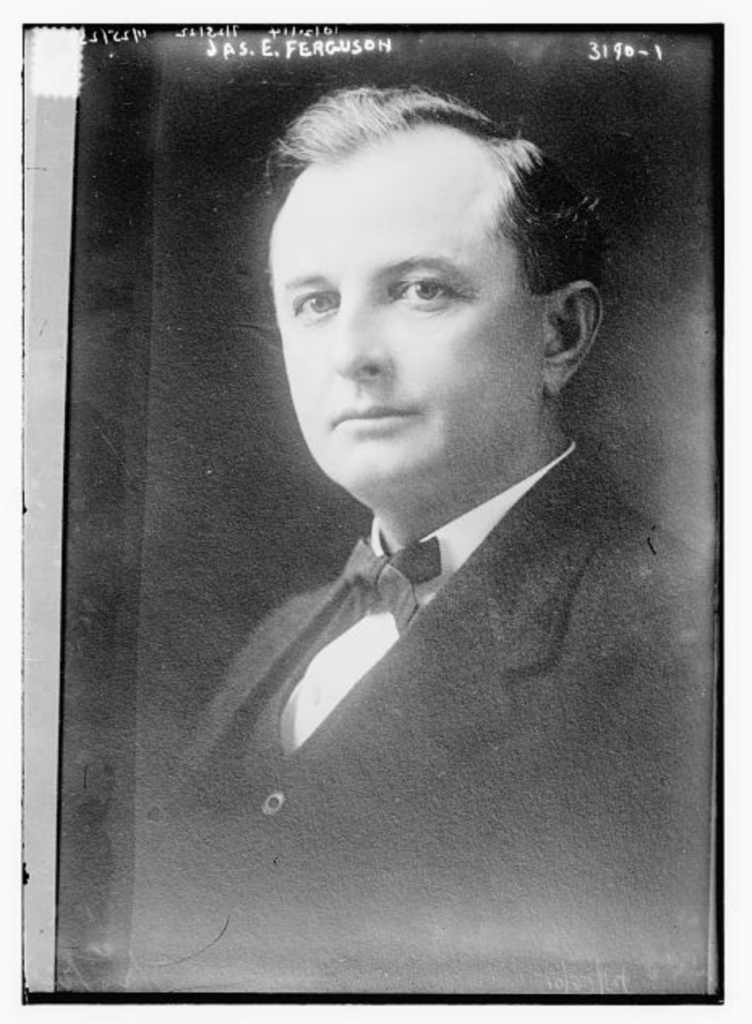

In 1917, Gov. James A. Ferguson, once a beloved populist, was impeached and removed from office after vetoing appropriations for the University of Texas the year before — and after House investigators reported that he’d misapplied and embezzled public funds. (He resigned the day before the Texas Senate cast its final vote affirming its judgment against him.) His career in politics ruined — he ran unsuccessfully for president in 1920 and for the U.S. Senate in 1922 — “Pa” Ferguson, as he was known, essentially installed his wife, Miriam “Ma” Ferguson, in the Governor’s Mansion in 1924. His role, at least publicly, was merely that of “first gentleman.”

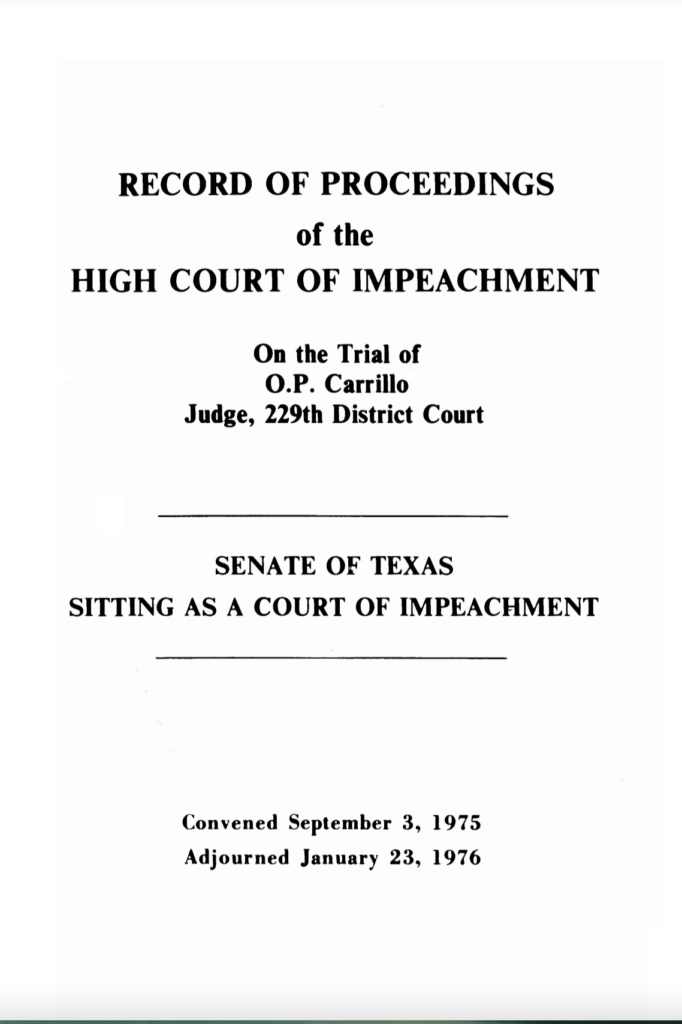

And in August 1975, state District Judge O.P. Carrillo, once a political ally of George Parr, the infamous patron of Duval County, was impeached by the House, which accused him of misusing public money and construction equipment, abusing his judicial authority and filing false financial statements. He was removed from office by the Texas Senate the following January, but impeachment, it turned out, was the least of his troubles: Carrillo was convicted of tax evasion and sentenced to 10 years in federal prison, of which he served 20 months.

Paxton, the Collin County Republican elected attorney general in 2014 and reelected twice since, was impeached May 27 for what a House investigative committee called a “longstanding pattern of abuse of office and public trust, disregard and dereliction of duty, and obstruction of justice and abuse of judicial process.” The charges stem from, but are not limited to, his request for $3.3 million in taxpayers’ funds to settle a wrongful termination suit filed against him by four whistleblowers in his office. They also said the attorney general abused his position to benefit a wealthy donor, Austin real estate developer Nate Paul, who was indicted this month on federal charges of making false statements to obtain loans.

Paxton’s trial before the Senate is to begin no later than Aug. 28. Since his impeachment, he has been stripped of his duties. The attorney general has denied any wrongdoing, calling his impeachment — by a House dominated by his own party — “a politically motivated sham” that is “illegal, unethical, and profoundly unjust.”

He will be represented before the Senate by Tony Buzbee and Dan Cogdell, two well-known Houston trial lawyers. Rusty Hardin and Dick DeGuerin, also leading lights of the Houston bar, will prosecute the case on behalf of the House.

Ferguson and Carrillo are the only two Texans convicted through impeachment, but not the only ones to face impeachment charges. Efforts by House members to remove Land Commissioner W.L. McGaughey in 1893 and District Judge J.B. Price in 1931 fell far short of the needed two-thirds vote of the Senate. McGaughey was accused by foes in the House of selling state lands illegally, and at bargain prices; Price, who presided over the 21st Judicial District east of Austin, was accused of “gross neglect” for approving excessive claims for reimbursement of expenses submitted by sheriffs in his jurisdiction.

In addition, four district judges were impeached during Reconstruction, when state government in Texas, as elsewhere in the fallen Confederacy, was placed under federal military rule — whose validity most Texans refuted.

Here’s a look back at the two impeachments sustained by the Senate, and the political careers they left in tatters.

From ‘Pa’ to ‘Ma’

James Edward Ferguson, the son of a Bell County farmer and Methodist minister, toiled in the fields from an early age. His father died when he was 4, leaving young James to help his mother cling to the family place, an experience that instilled in him a lifelong empathy with sharecroppers and other poor rural folks.

He left home at 16 and drifted through the American West, working odd jobs before returning to Texas to study law. He was admitted to the bar in 1897 and opened a practice in Belton, south of Temple. A shrewd businessman, Ferguson invested profitably in Central Texas real estate, insurance and banks. In 1914, he won the Democratic nomination for governor — tantamount in those days to election — campaigning as a friend of the small farmer and a foe of Prohibition.

“The campaign proved him to be a man of considerable native ability and the possessor of a captivating personality,” according to the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas at Austin. “As a political speaker he had few equals.”

He was reelected in 1916 but quickly and unwisely picked a fight he couldn’t win with the University of Texas. When UT’s Board of Regents refused to remove six faculty members whom the governor found objectionable, he vetoed practically the entire appropriation for the university, drawing the wrath of the many Texas legislators who venerated the school.

Ferguson’s formal schooling had stopped at sixth grade. “Being a self-made man, who had not experienced the benefits or damages of higher education, he naturally entertained some doubts as to its ultimate importance,” wrote Cortez A.M. Ewing, a University of Oklahoma professor, in the June 1933 issue of Political Science Quarterly.

Ferguson’s petulant move to defund UT triggered an impeachment investigation that spread to charges of misappropriating funds, directing deposits of state money into banks in which he held a stake, lying about his financial ties to those banks and refusing to disclose the source of a $156,000 loan — more than $3.7 million in today’s dollars — later believed to have come from the brewing industry.

James “Pa” Ferguson

Miriam “Ma” Ferguson

He dismissed the legislative inquiry as a “kangaroo court,” but on Sept. 22, 1917, the Texas Senate, by a 25-3 vote, dismissed him as governor, sustaining 10 of 21 impeachment counts brought by the House.

Ferguson contended that his resignation one day before the Senate entered its final judgment rendered moot that body’s finding that he was disqualified “from holding any office of honor, trust, or profit under this State.” But the voters would have none of it. In 1918, he sought the Democratic nomination for governor but lost to William P. Hobby, who had been lieutenant governor. In 1920, Ferguson ran for president as the candidate of the American Party, but, on the ballot only in Texas, he received just 0.2 percent of the popular vote nationwide. In 1922, he ran for the U.S. Senate and was again defeated.

From the ashes of Pa’s career arose the phoenix of Ma’s. Ferguson successfully promoted his wife’s candidacy for governor in 1924. She told crowds that voting for her would get them “two governors for the price of one,” and one of her campaign slogans was, “Me for Ma. And I ain’t got a dern thing against Pa.” Miriam Ferguson served for two years, then won a second, nonconsecutive two-year term in 1932.

Ma Ferguson was the first female governor of Texas — and barely missed being the first in America. The same year she was elected, Wyoming voters chose Nellie Tayloe Ross to succeeded her husband, William B. Ross, who’d died in office. Ross was sworn in on Jan. 5, 1925 — 15 days before Ma Ferguson’s inauguration in Austin.

Miriam Ferguson was a fierce opponent of the Ku Klux Klan and of Prohibition. She supported public education, the merciful treatment of prisoners and, in her second term, FDR’s New Deal. She might have carved out a notable place of her own as a pioneer in Texas politics and an early feminist icon if she hadn’t been universally perceived as the puppet of her dishonored husband.

As Jan Reid wrote in Texas Monthly in September 1986, “She is remembered as the ultimate figurehead, a woman who sought power only so that a man could exercise it.”

From political boss to petty thief

Until his downfall, Judge O.P. Carrillo stood high in the ranks of the Democratic political machine that ruled South Texas for decades.

Olivera Peña Carrillo was born and raised on the ranchlands outside Benavides, a now-vanishing Duval County town. He was a son of D.C. Chapa, a right-hand man to George Parr, the “duke of Duval.” Carrillo served as the secretary of the Benavides school board and Duval County attorney before pushing for the creation of the 229th State District Court in Duval, Starr and Jim Hogg counties in the late 1960s and then serving as its first judge. One of his brothers, Oscar Carrillo, was a member of the Texas Legislature. Another, Ramiro Carrillo, was a Duval County commissioner as was his grandfather, Eusebio Carrillo, who helped establish what would become the Parr political machine.

When he wasn’t attending to (or, as the Legislature would eventually conclude, profiteering from) his judicial duties, Carrillo liked to spend time on the 16,000-acre ranch his family had amassed west of Benavides.

“I like to get out on the ranch and work alongside the hands fixing fences, repairing windmills and working cattle,” he told the Corpus Christi Caller-Times in 1975.

“But my real job is ranch cook. I make the best cowboy stew in South Texas.”

Like Parr, who died of suicide in 1975 after his conviction on federal charges of income-tax evasion, O.P. Carrillo came under fire for abuse of office and for using county resources for his personal benefit. After breaking with the Parrs in the mid-1970s — among other acts of defiance, he pushed for the removal of Archer Parr, George Parr’s nephew, as county judge — Carrillo was impeached in 1975. The Texas House accused him of, among other things, buying groceries for himself, his employees, his guests and his brother Ramiro with public funds earmarked to help feed the poor; using his judicial authority to protect political friends and punish political enemies; demanding that government employees, using government equipment and government materials, make improvements to his property; and filing fraudulent financial statements with the Texas secretary of state.

Leon Jaworski, the storied Houston attorney best known (at least outside Texas) for his role as special prosecutor in the Watergate scandal, served as special advisor to the Senate for the Carrillo impeachment, at no cost to the state.

In January 1976, the Senate sustained by a two-thirds majority one of 10 impeachment articles referred by the House. Carrillo was acquitted on one count; the other eight were dismissed with no decision as to their merits, since a vote to remove him on one was sufficient. The Senate’s final judgment was adopted on Jan. 23, 1976, by a 26-1 vote.

Almost concurrently with his impeachment, Carrillo was indicted by a federal grand jury in the Southern District of Texas on charges of income-tax evasion. He was convicted and sent to a federal correctional institute in Fort Worth, where he served two and a half years.

Barred from holding public office again, he operated a trucking business after his release from prison. In the mid-1980s, he worked for a time for the San Antonio Gunslingers, the United States Football League team owned by his friend Clinton Manges, a flamboyant (and felonious) South Texas rancher, oil tycoon and Democratic Party kingmaker.

After the Gunslingers collapsed in 1985 — Manges essentially walked away from the failing franchise, stopped paying its bills and left players and staff holding the bag — Carrillo largely disappeared from public view until what the San Antonio Express-News described as “a bizarre incident in July 1989, when he was accused of shoplifting a $6.99 bottle of vitamins from a North Side grocery store.” The once-fearsome South Texas powerbroker was issued a misdemeanor citation and released. On Aug. 25, 2001, he died in an Alice hospital after a crippling stroke. He was 77.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story incorrectly said Ferguson and Carrillo were the only two Texas officials previously impeached. It also misstated the role of Leon Jaworski in the Carrillo impeachment.